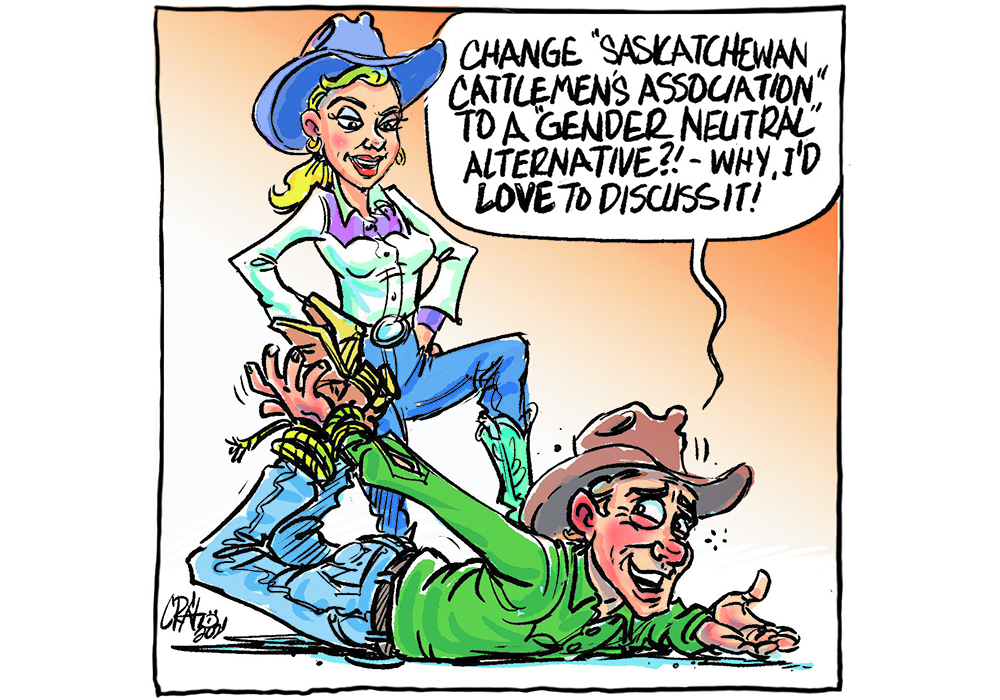

Last week members of the Saskatchewan Cattlemen’s Association decided not to instruct their board to pursue a name change that might have resulted in gender neutrality.

It is a surprising development that the organization might want to rethink. Yes, in today’s society there is an often wearying sensitivity to political correctness but acknowledgement that both genders play a vital role in the cattle business, and indeed the agricultural industry as a whole, bears consideration.

Some may think a gender-neutral name change is a “liberal” idea. That connotation can be particularly galling given the conservative nature and history of farming and ranching in Western Canada — a history both genders played a role in building and continue to have a role in developing.

Read Also

Proactive approach best bet with looming catastrophes

The Pan-Canadian Action Plan on African swine fever has been developed to avoid the worst case scenario — a total loss ofmarket access.

There is much to be said for tradition. Agriculture is generally a traditional business. Financial barriers to entry are so high that few new folks come into farming and ranching, so those already there must remain. Tradition is integral to their operations. History makes agriculture possible.

This doesn’t mean agriculture fails to adapt to technology or management advancements. These are necessary for survival. In the case of the cattle business, genetic research, effective vaccines, feed conversion improvements, pain management techniques, greenhouse gas and carbon managment and sustainability measurement are a few examples of an evolving and steadily improving sector. It continues to develop tools to modernize and evolve.

One of those tools is marketing, and an organizational name that fails to reflect diversity is a name that should be reviewed to ensure it says what its members want it to reflect in the wider world.

As an organization, the SCA is relatively new. It was formed to manage the beef cattle checkoff in 2009. In contrast, the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Association was established in 1913 and even then, in more conservative times than the ones we are living in, its members chose a name that reflected both genders.

The Western Stock Growers’ Association was formed in 1896 with a similar reflection. Alberta Beef Producers and Manitoba Beef Producers, newer than either of the latter two groups, also chose their names with care to inclusion.

Name changes are difficult in any industry. When businesses or organizations have been around for decades, their brands might not be adaptable to a name change that has a more acceptable public fit.

Any group considering a rebranding must weigh the risks against the threats of not doing it. It must own the traditions that support its name.

The SCA does not exclude women by virtue of its name. At the time of formation, it was likely a choice made with thoughts of expediency and simplicity. Its female members are not offended by the name, else they wouldn’t be members.

But we live in times when attention to diversity is ever present. Those outside the cattle business — consumers, customers and society writ large — could be forgiven for taking the SCA name too literally.

The livestock industry and agriculture as a whole have to be able to explain themselves to anyone who asks. How often we now hear that farmers and ranchers should “tell their stories” so that a society that has shifted inexorably to urban life can understand its practices and challenges.

How does the SCA explain its name to those without deep roots in rural tradition? Perhaps it can and if that is the majority view, it should have an internal discussion on how to do that.

The group must consider how its activities intersect with customers and governments and how the name appears to the self-proclaimed “woke” elements of society.

It should also consider that businesses viewed as small-c conservative are not treated as favourably as those with more “progressive” faces.

As an important part of the cattle industry, the SCA should have a conversation about its moniker.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen and Mike Raine collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.