The world’s population is expected to surge to nearly 10 billion people by 2050. How will farmers manage to feed everyone?

The premise of this year-end edition is that increasingly sophisticated science and technology will be applied to agricultural production in the coming years.

This development will be driven in part by humanity’s natural inclination to improve and evolve — to get bigger and better.

However, another driver will be the inescapable reality that the world’s population wants more food every year and with finite resources of land and water, the only way to produce more is to use science and technology to generate more food production from each unit of input.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

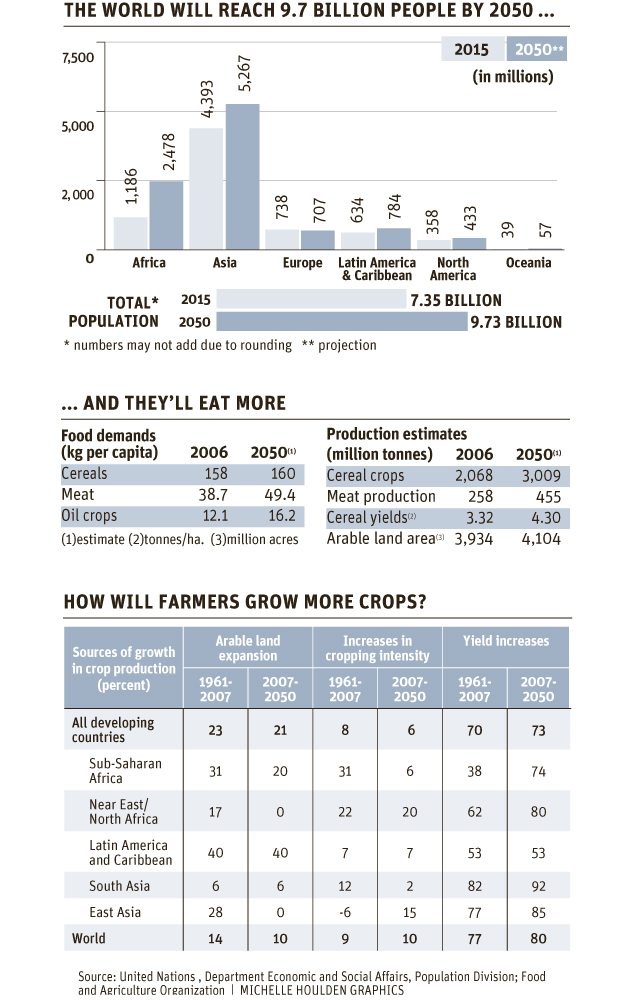

The United Nations projects that the global population will increase to around 9.7 billion people by 2050.

That is more than two billion additional mouths to feed compared to today.

Rising standards of living in the developing world will change dietary standards, including a demand for more vegetable oil and meat protein.

In the discussion of this trend, the statistic often presented is that global demand for food will rise by 60 percent by 2050.

That number comes from analysis by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, initially stated in 2006 and updated in the paper World Agriculture Towards 2030/50: the 2012 revision, by Nikos Alexandratos and Jelle Bruinsmas of the FAO’s Agricultural Development Economics Division.

The FAO projects that 70 percent of that increase would be the result of population increase and 30 percent the result of income growth. This would spark increased demand for meat, which requires more resources to produce than crops.

The FAO expects that demand for cereal grain would grow to about three billion tonnes by 2050, up almost one billion from now.

Meat demand is projected to rise by more than 200 million tonnes to a total of 470 million tonnes.

The FAO projects that 80 percent of the production increase will have to come from yield increases, while 10 percent will come from increasing cropping intensity and another 10 percent from expanded acreage.

A 60 percent increase in global food demand sounds like a lot, but it is not unprecedented.

Indeed, the FAO forecasts that global food demand and production will rise by 1.4 percent per year or less.

That is slower than the pace for most of the preceding 50 years, which was the period of the green revolution with its introduction of fertilizers, high yield crop genetics and pesticides.

Global crop production growth was 2.2 to 2.3 percent per year for most of that period.

Also, the pace slowed at the start of the current century, partly because the innovations had become widely adopted.

Some observers wondered if the new science of genetic modification would deliver the same momentum of production increases as the green revolution.

Farmers were also reluctant to invest to expand production because the green revolution’s success had led to a buildup of stocks that depressed prices.

This contributed to a period of slower crop production increases, particularly in the 1996-2003 period, but then the pace recovered.

Overall, FAO believes the goal of achieving a 60 percent increase can be met, so long as there is the commitment:

“Barring major upheavals coming from climate change and the energy sector or other events that are difficult to foresee — such as wars or major natural catastrophes leaving long-enduring impacts — world agriculture should face no major constraints to producing all the food needed for the population of the future, provided that the research-investment-policy requirements and the objective of sustainable intensification continue to be priorities.”

Those interventions include support for agricultural research as well as provision of education, credit and infrastructure to make it profitable for farmers to expand production capacity, the report said.

Food production increases will face new challenges, the FAO noted.

Irrigation expansion will face strong competition for fresh water from urban populations. Urban growth will spread into farmland.

Efforts to preserve forests and grasslands for ecological and wildlife needs will restrict the amount of land that can be cultivated.

Global climate change might be the biggest wild card. Its potential for more changeable and intense weather events presents challenges for increased food production.