Trochu, Alta., promotes itself to city residents who no longer have to work in an office, but digital access remains a barrier

A small Alberta town views the growing number of city residents working online from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for rural communities to reverse a decades-long trend.

The crisis has proven that many people don’t need to live in a city because they no longer have to commute daily to work, said Jamie Collins, an administration official for the Town of Trochu southeast of Red Deer.

If they’re “looking to get out of a big-city mortgage, it can be more economical to live in a smaller community,” she said.

Read Also

Nutritious pork packed with vitamins, essential minerals

Recipes for pork

“I just think there’s nothing like it — the connection with people … and just the safety,” she said, pointing to lower crime rates and how people know their neighbours.

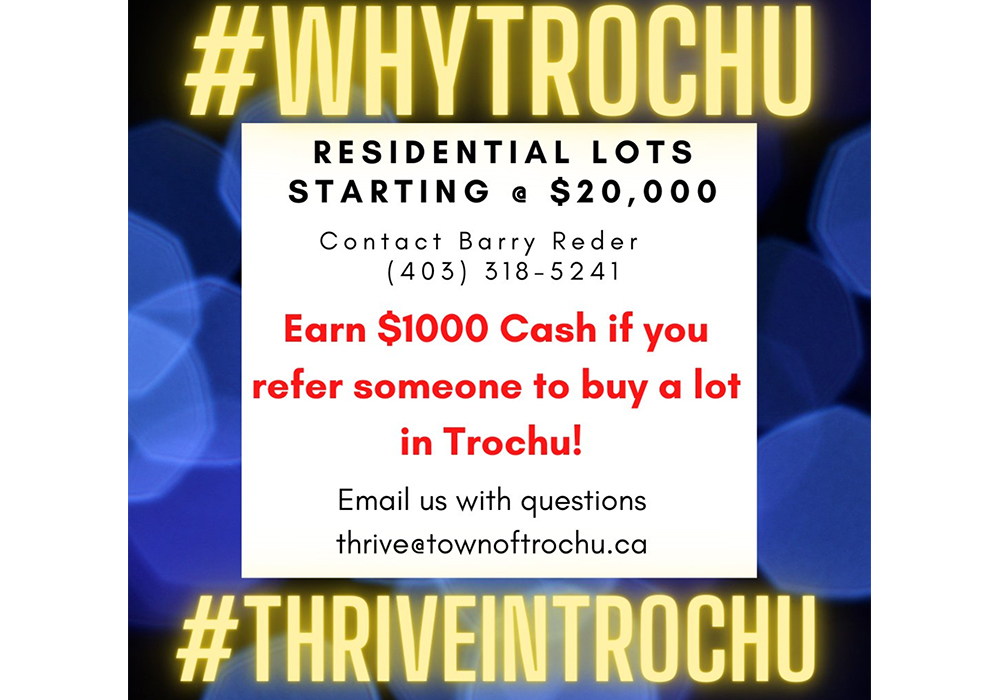

The town of about 1,000 people recently launched the Why Trochu marketing campaign to attract more residents. It is offering $1,000 to people who successfully refer home buyers to the community.

The campaign will include digital content such as a series of videos on YouTube, along with social media posts under the hashtags #WHYTROCHU and #THRIVEINTROCHU, said a statement by the town.

“The Town of Trochu believes these unprecedented times have created a unique situation full of opportunity for rural Alberta … If people are working from home and can live anywhere in this great province, why not choose Trochu?”

Paul McLauchlin, president of the Rural Municipalities of Alberta, said it is a fantastic idea. Friends in Calgary have told him some of the city’s larger companies will likely get rid of office space emptied by the pandemic, which means working remotely from home could become a permanent fact of life post-COVID.

“I think they’re really promoting their employees to say, ‘hey, you can live wherever you want as long as you can get to the office once a month’ or something like that, which is really a net benefit to places like Trochu.”

The fact the town is “actually picking up on that and looking to attract people is a great idea because in some parts of Alberta, some of the smaller centres have been depopulating, so this is a fantastic opportunity for people to move into our communities and grow our communities again.”

But as much as the pandemic is creating new rural opportunities such as working from home, it has also revealed the depth of obstacles such as digital poverty, said McLauchlin, referring to a term for lack of internet access.

Sufficient access to be able to work remotely is still hit and miss in rural Alberta, “and so there’s really this huge digital access gap that occurs,” he said. Although some of it is due to technical constraints caused by geography, areas such as the eastern dryland belt in southern Alberta have a population that is too low to be profitable for large telecom companies.

Collins said Trochu lacks the fiberoptic internet enjoyed by city residents, but instead residents use service providers such as Xplorenet.

“It runs everything that people need, or businesses would need, for sure.”

A survey of RMA members recently revealed that rural municipalities are owed $245 million in unpaid property taxes by Alberta’s ailing oil and gas industry, up from $81 million in 2019. The energy sector is shifting from its former prominence as the main driver of Alberta’s economy, said McLauchlin, who is also reeve of Ponoka County.

“We may have a couple of years of a boom time when we’re emerging from COVID … but in the long term, we really need to focus on diversification. My personal belief is that we need to be investing in our entire agricultural industry, which needs to be our next big thing.”

Such diversification requires investment in rural high-speed broadband internet by the provincial and federal governments, he said.

McLauchlin is a member of the board of governors for Olds College in Alberta, which includes a Smart Farm that acts as a living laboratory for high-tech agriculture.

He said access to broadband is important for things such as precision agriculture, which requires the ability to handle huge amounts of data to maximize yields, while reducing inputs such as pesticides or fertilizers.

“That is the future of agriculture. There’s tremendous opportunity, and the telemetry needs to be there: the 5G, the Internet of Things,” he said, referring to a growing convergence of technologies and devices that exchange data through the internet.

He called rural hopes about broadband a Field of Dreams conversation, referring to the 1989 baseball movie starring Kevin Costner.

“If (Trochu) got a fibre line into their community, it is Field of Dreams. I mean, ‘if you build it, they will come,’ and I think people will start realizing that you can run very successful, knowledge-based businesses out of smaller towns with lower per-sq.-foot rental prices. It’d be phenomenal.”

McLauchlin and his wife have worked remotely for about 18 years from their farm near the hamlet of Bluffton, Alta. He has operated an environmental consulting business that has been involved in projects ranging from major pipelines to Indigenous engagement.

He said he enjoys a higher quality of life as a rural resident, pointing to the wide-open spaces on his farm and having a sense of wildness from seeing animals such as moose, bears and squirrels.

“I’ll visit friends in the city and go into their backyard, and other people can see into their backyard. It’s just such a fascinating thing to me now. I can walk around my place and I just don’t have that density.”