On the Farm: The younger Thomsons hope to build a business that grows ‘slowly but surely’ and stays in the family

Making money is not the primary reason Aidan Thomson started farming four years ago.

“I love being outside, love connecting with the wilderness,” said the 21-year-old First Nations grain farmer from the Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation.

Thomson grew up on a farm on the reserve, where he has fond memories of watching tractors drive by.

“It was kind of cool for me seeing those big machines coming down the road,” he said.

When he was old enough he got his turn behind the wheel and loved it. He enjoyed the solitude and taking in the early morning and late evening panoramas.

Read Also

Nutritious pork packed with vitamins, essential minerals

Recipes for pork

Aidan’s father, Perry Thomson, took over a mixed operation from his dad and farmed it for a while until multiple years of soaking wet conditions and faltering equipment forced him out of business.

“We kind of packed it in after that,” said Perry.

“It was a struggle back then.”

He immediately got a good job in the pipeline business and did that for a couple of years before switching to social work.

Perry is now part owner of Prairie Spirit Connections, an organization committed to improving the conditions and well-being of aboriginal people. He has three sons and a daughter.

He was out of farming for 14 years when his two youngest sons, Aidan and Perry Thomson Junior, approached him with the idea of starting a grain farm on the reserve.

It didn’t take long to gain his support for the proposed venture.

“I love it because I grew up like that,” said Perry.

“Now when I hear my boys talk, they talk about being out there on the land. It just does something to you.”

It does something to Perry as well.

“It’s damn good therapy, boy. I don’t know about the bills and that, but it’s just good to be out there,” he said.

The Thomsons have converted 1,400 acres of pastureland back into grain production. They plan to break up another 600 acres soon.

The land belongs to the reserve but the canola, oats and barley belong to the Thomsons.

Perry calls Aidan the boss of the operation, but he does the seeding and sells the grain. His sons work the cultivators, choppers, swathers, combines and grain trucks.

They are taking a different approach than many modern farm operations, choosing to seed half of the land every year and leave the other half in summerfallow. That is how it was done when Perry was helping out his dad.

“We kind of have that belief in giving the earth a rest,” he said.

“The odd time we spray it but a lot of times we go the old style and break it up and get it really good for the year.”

He also wants to get back to growing winter wheat, which is a crop that he planted a lot in his younger days.

While some things stay the same, there have been other dramatic changes on the farm.

The family recently bought some 60-foot cultivators, instead of the old 12-foot machines they used to operate.

The upgrade allows them to get their farm work done quickly and get back to their other occupations. Perry’s sons do social work with him at Prairie Spirit Connections.

Perry said the economics of farming has been pretty good this time around, especially with the recent bull run in grain markets.

Aidan said his goal is to build a business that grows “slowly but surely” and stays in the family. Every year he is absorbing knowledge that he can pass down to the next generation.

At one point, the family was contemplating adding cattle to the operation but his uncle, who is a cattle farmer, advised against it.

“He let me know that cows are an every day job. No matter how you are feeling you have to check on your cows,” said Aidan.

There is also a big issue with stray dogs on the reserve and they can pose a problem come calving time.

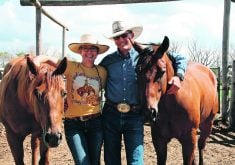

So for the time being it’s going to remain a grain farm with a whole lot of horses. Aidan estimated they have just shy of 50 horses, including 15 or 20 riding horses.

He got his first horse when he was about five years old and grew up around his uncle, who was a true horseman.

Aidan would watch his older cousins and brothers saddle up in the mid-afternoon and not return until late evening.

“That was really something that was cool because the horse in itself is a very strong and proud individual animal,” he said.

He found it amazing how that proud animal would allow somebody to sit on its back and ride it around all day.

It is all about forming that connection, which is the same feeling he is developing with the land each time the tractor makes an early-morning or late-evening pass across a field.