Winnipeg’s Farmer’s Edge partners with San Francisco’s Planet to get a Dove’s eye view of the field

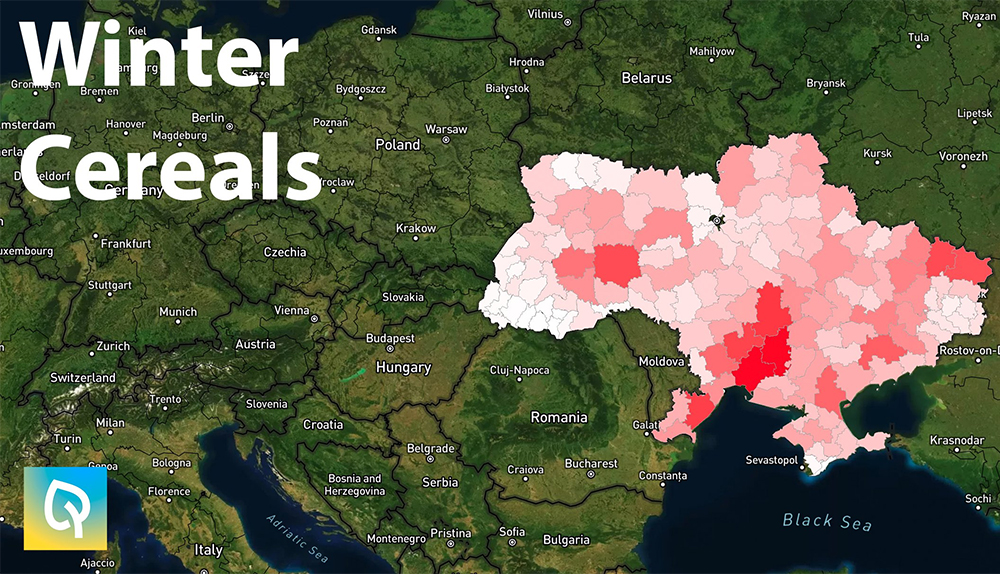

A bird’s-eye view can provide intelligence about crop conditions that would otherwise be found only at harvest or by a combination of luck and labour.

The problem is that in the past the birds didn’t fly every day.

Canadian agronomy company Farmer’s Edge and San Francisco’s satellite imager Planet have joined forces to make new images available nearly every day.

That might seem like overkill, but producers could find themselves making use of the high frequency imaging more than might be initially imagined.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

“It’s kind of addictive,” Wade Barnes, chief executive officer of Farmer’s Edge, said about getting near real time field imaging from above. “We were looking for a solution to this issue.

“We used drones and satellite (images), but farmers need to be able to react more quickly to stress issues in their crops. But first they have to know about it.”

Aerial imaging forms the foundation of many precision farming systems. Producers can arrange for satellite views of their fields, but they might get a dozen or so images in the short prairie season.

Of those, some might have been shot on cloudy days, meaning no images.

Alternatively, farmers can hire drone imaging or tackle the job themselves but then they need to also handle the resulting large, geo-referenced data files and convert these into something useful.

There are few players that will also take care of the conversions, and even fewer that will do it quickly.

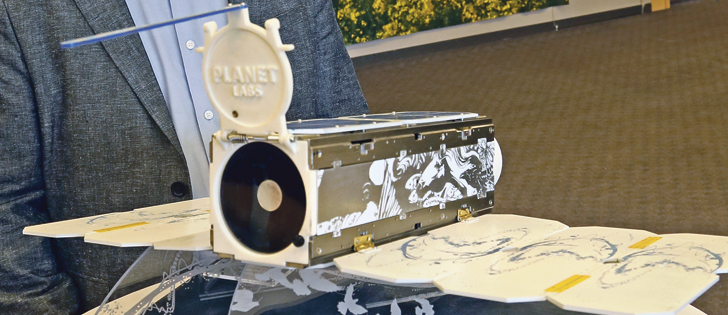

Planet is known for its constellation approach of mini-satellites.

“We have 190 satellites working today, gathering about 200 million sq. kilometres (of data imaging) every day, 12 to 13 terabytes,” said Josh Alban of Planet.

“We have the world’s largest automated pipeline to manage the processing of 800,000 images every day to look at and make sure they are right.”

As well, the Rapid Eye satellite imaging that Farmer’s Edge was using has been acquired by Planet, which also recently bought Google’s Terra Bella and SkySat, a high-resolution video imaging operation.

“We are now in the Google Cloud. We took some of their satellites and they took some our (data) storage, management issues,” he said about the massive amounts of information the company is now managing.

Barnes said with Rapid Eye alone “it really didn’t deliver on the reliable data (flow) we felt we needed. We have to be making a consistent offering to farmers (from) Saskatoon to New South Wales (Australia).

“Every two the three days we can get an image and that is what it takes. On my own (Manitoba) farm, we have been getting an image every day for the past month.”

Lyle Jensen of Nobleford, Alta., manages agronomy on about 30,000 acres and has been trialing the Farmers’ Edge product for the past few months.

“I can’t get to every field every week. I need to be able to get a look and decide selectively where we need to get more information. Full section fields, or some three section fields can take all day to scout,” he said.

“In 30 seconds I can call up a field and start making decisions. I can’t get my drone out in 30 seconds.… I’m still using it for scouting, but that is all,” said the Alberta agrologist.

Added Barnes: “(The) biggest problem with (satellite) imagery, once the farmer gets it, they want more. And then when we don’t have it, they get mad, and they get frustrated. They need it when they need it.”

Alben said Planet chose Farmer’s Edge because “they want to be global, best in class and that is where we wanted to be (in agriculture).”

Added Barnes: “(The) deal is long-term, multimillion-dollar in key agriculture markets … Canada and the United States (as well as much of South America, Australia, South Africa and the former Commonwealth of Independent States). If farmers want access to an (agronomy) platform with Planet, they will have to work through us.