It’s a truly dark time in Canada, with the rise of an angry, raging, denunciatory politics taking over this nation the way that it has been doing in the U.S. for a few years now.

The federal election supplied ample evidence of this, with ill will and personal attacks hanging over the entire campaign. Beyond the unpleasant personal attacks on party leaders, the campaign also contained region-versus-region animosity, urban-versus-rural friction and ugly language that fell to levels not seen in recent memory. It had a nasty feeling, and that wasn’t dissipated on the morning after, when instead of the customary offers to try to work together and find common ground, Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s premiers took the opportunity to confront and denounce the just re-elected Liberal government with what amount to an ultimatum and threats of secession. (Manitoba’s premier was a notable exception to his Prairie counterparts, offering an olive branch to the federal government and showing irritation with western separation talk.)

Read Also

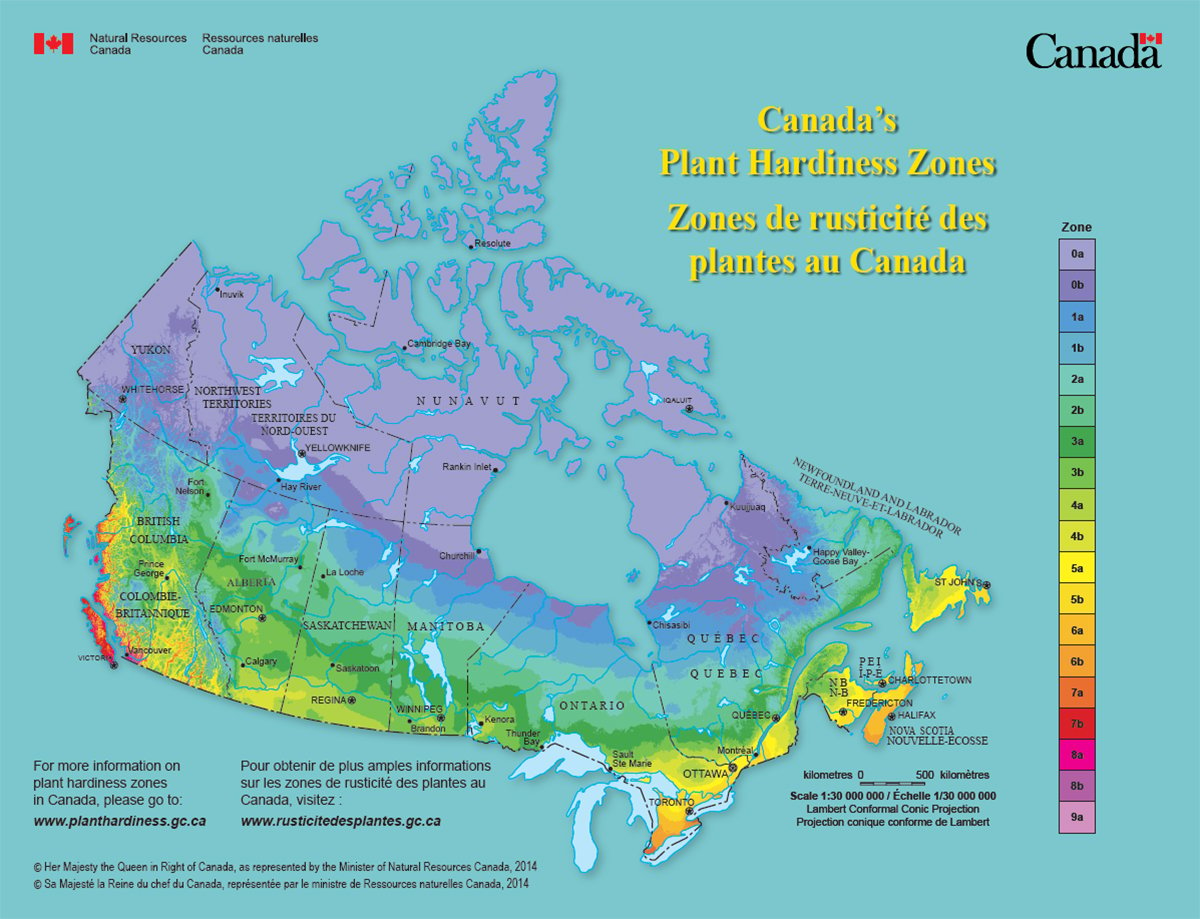

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Most people think the animosity comes from pipelines, from carbon taxes, from progressive social policies and conservative reservations to those policies. Some think it’s a cultural thing, with urban and urbane politics and politicians clashing with those of the country and rural society. Some hate Justin Trudeau’s goofy socks and public apologies. Others hate Andrew Scheer’s manner and dimples.

I suggest the angry and infuriated tenor of our times comes from none of these, which are just sparks that light a fire built on a stack of fuel piled high by something nobody is to blame for: the commodity bear market.

I’ll bet I just lost half my readers there. It’s not the most exciting explanation. But I think all this ill will, resentment, anger, outrage and frustration comes from Canada’s economic situation since the end of the commodity boom, which last from about 2001 to 2014. (It was shorter in agriculture, lasting only 2006-14.) Canada’s national economy is greatly influenced by commodities, which bring great economic activity, wealth and taxes to this sprawling but sparsely populated country. Western Canada in particular, with its economy dominated by oil and gas, agriculture, forestry and mining, does terrifically well in commodity booms. In commodity bear markets it does poorly.

It’s been about five years since the commodity boom ended. I’ve spent a lot of time studying commodity cycles, and the sad reality is that commodity booms tend to last for a shorter period than commodity busts, and there’s little reason to believe that a multi-year commodity bull market is going to be on the horizon any time soon.

That leaves Canada, Western Canada, Western Canada’s energy industry and farmers dealing with an economy in which the bills have been coming due, the expectations many built their businesses and strategies upon are falling apart, and the recently so-bright future now looks bleak.

This is the kind of situation in which many will look for somebody to blame, and many have found a somebody. It might feel good to point the finger at and yell about Trudeau, Scheer, farmers and oil workers, urban envirnonmentalists, Indigenous people, “settlers,” etc. But that won’t do much. Government only operates at the margins of the economy in open market societies like ours, so whoever wins or loses elections has a lot less impact upon our lives and industries than we would like to believe. Governmental change will literally have only a marginal impact on how we’re doing.

The best analysis I’ve seen suggests we shouldn’t expect another long-term commodity bull market until the late 2020s, so resource producers, such as farmers, need to be hunkering down for a long haul of break-even returns on average, some years of losses, and the occasional one-year bull market when somebody’s crop gets wiped out.

Back in the bull market days, many in the oil and gas industry were indulging in a warm and satisfying bath of Peak Oil Theory, which promised permanently high prices for energy. (Can you believe that we still thought that just ten years ago?) Farmers have had oodles of futurology speakers telling them all about how the world will need their crops more and more because, after all, we have feed nine billion people by 2050 and the world is running out of arable land and water. Farmers are still being sold that story. To me, it seems like another hubristic belief that exists on awfully wobbly legs. (To see work on this issue, see China: Dangerous Assumptions)

Now we’re in a starkly different environment, and many are well into hunkering-down mode. There’s not much for an individual to do about this other than being the best producer and business manager one can be. It might feel good to rage against politicians and various groups in the Canadian population that drive us crazy, but in the end, the general tough times for Canada don’t come from any of us, and the solutions aren’t going to come from denouncing, attacking or raging against any of our fellow citizens. It’s one thing we’re all in together, unified in a period of frustrated hopes, even if we can’t see beyond our outrages to realize it.