It’s been interesting covering this Dutch Disease uproar that the NDP’s leader, Thomas Mulcair, kicked up by blaming the West for the east’s economic woes. I wonder if he’ll be excited by his trip to Suncor this week, seeing all the economic activity, jobs and taxes getting produced up there. Or will he be annoyed by seeing Westerners doing well when his own province is in decline, and be annoyed by the total absence of the sound of people banging pots and pans together?

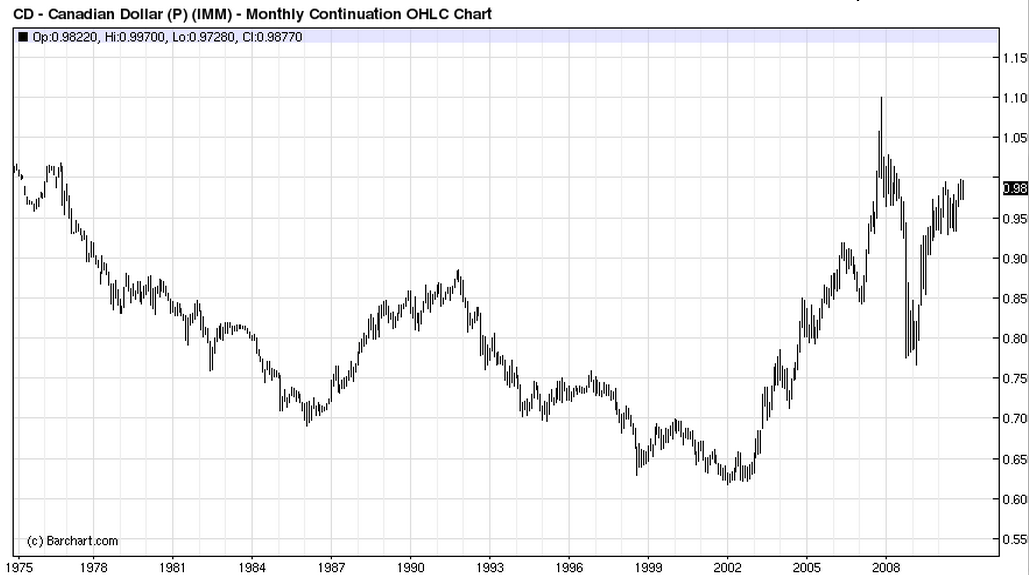

The funny thing is that the east doesn’t have much to complain about really, since that region is quite well insulated from the effects of Dutch Disease. Sure, the loonie has risen, but only to where it was when I was a kid. Actually, it’s about 10 percent below that right now, because I remember going to Minot as a kid in the 1970s and the Canuckbuck was at a premium, and I felt very cocky.

Read Also

Rural communities can be a fishbowl for politicians, reporter

Western Producer reporter draws comparisons between urban and rural journalism and governance

That plus-par Canadian dollar gave me a lot of buying power in Minot.

But as you can tell from the chart above, that seemed a lost golden age of wealth as I grew older, because the dollar fell steadily for years through the late 1970s and much of the 1980s, rose in the late ’80s, but then began that long, long slide that many Canadians know believe is “The way things should be.”

Or at least that’s the way things might seem to tend to be, if you don’t look back to the 1970s. That’s why manufacturers – including our own hog and beef industries, which manufacture feed into meat – see the rise since 2003 as something anomalous. It’s a problem that some, such as Mulcair, think needs to be fixed.

But why is that so? Those periods of declining dollar values were also times of low, low commodity prices. Is that the way the world should be? Why do low commodity prices make more sense than high commodity prices? What is it that makes the periods of low commodity prices normal? What is the “right” price for commodities?

I’d say the right price for commodities is whatever price the market will pay for them, so both low and high price periods are “right” in that respect. And that should be reflected in the currency exchange rates. We’re in a commodity boom now, so the dollar is probably above its long, long time average value. So you could say it’s overpriced, but only in the context of the assumption that the commodity boom will end some day. You could also say the Canadian dollar was badly undervalued for those periods in the 1980s and 1990s when it hit the 60-something cents level. You could see that as an underpriced dollar, but only if you assume that commodities won’t always be dirt cheap.

I worry about Dutch Disease, but for the West, not the east. The commodity boom and oilpatch boom has made farm labour extremely expensive, and that shaves margins and makes operating difficult for many farmers. In response, many have bought lots of land, big equipment, and brought in professional management to ensure everything’s running with peak efficiency. That’s the most sensible response to Dutch Disease pressures and what all producers – agricultural and industrial – should be doing about it. Reinvest and improve.

That has had the effect of bidding up land prices to very high levels (compared to the past) and surging commodity prices have made farm machinery very expensive. So there’s a lot of debt piling up out there in the search of maximum efficiencies. All based on the assumption of continued high prices for crops and meat. That assumption has been correct for years and farmers who have expanded and increased efficiency have made piles of money more than they would have if they hadn’t upgraded their operations.

But there comes a time when commodity prices fall, which can be a problem because the debts don’t fall. Farmers who pile in at the end of the trend have a high chance of getting burned. As a wise agricultural economist I know has repeatedly noted: a farm boom now tends to mean a farm crisis a decade later. One creates the other.

So how do you balance those needs? To deal with the increased cost of labour and inputs you mechanize, automate and expand. But to stay protected you need to keep debts low and exposures minimized.

How can you do both at the same time?

I can see why farm management consultants have such a booming business . . .

But just as it was probably a poor assumption of manufacturers that Canada could endlessly depreciate its currency against the U.S. dollar to stay competitive, it’s also a poor assumption that high commodity prices are here forever. If we’re lucky we’ve got a few more years left of this high-price commodity cycle. Some think it could last another decade. Others think it’s already ending.

Best to be prepared for both scenarios.