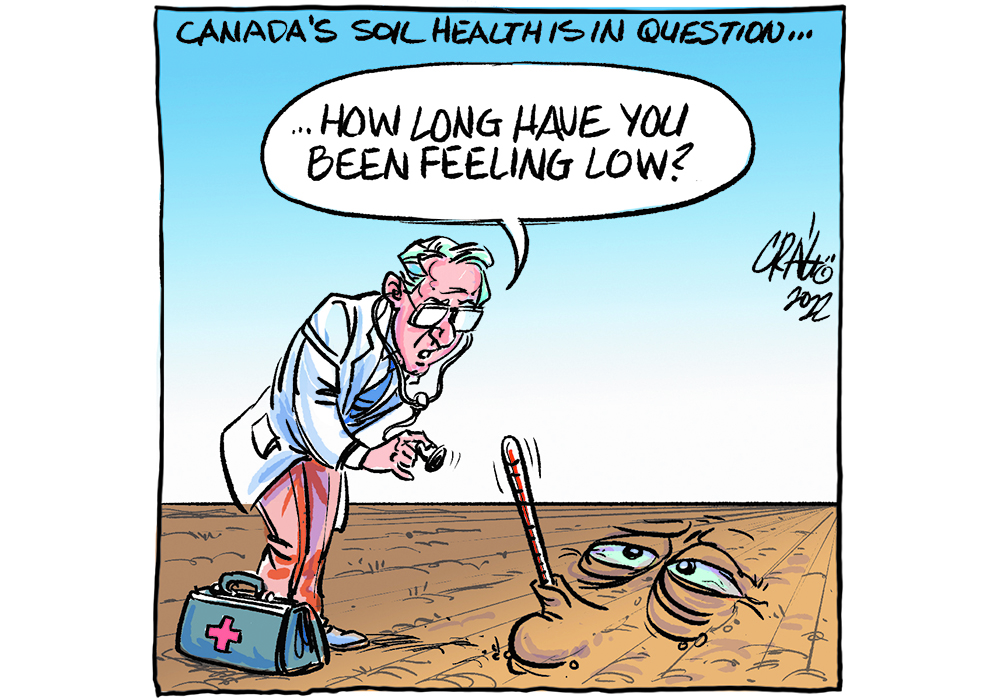

Soil health is a phrase the general public can get behind, even though most producers and agronomists would have trouble describing what it is in exact terms.

That’s not because they don’t know. It’s because there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to healthy soils. Most agree on one thing: the more organic matter there is in soil, and that leads to more carbon, the healthier it is.

Simple descriptions of a healthy soil might suggest it stores water and nutrients with few losses to the environment. A more complex description suggests that minimizing erosion, compaction, salinization, contamination and urbanization lead to a healthy soil.

Read Also

Farmer ownership cannot be seen as a guarantee for success

It’s a powerful movement when people band together to form co-ops and credit unions, but member ownership is no guarantee of success.

Things get muddy when talk turns to the methods and policies that would characterize the latter description.

Canada last took a national look its soils in the mid 1980s when the federal government created its Soils at Risk report. It called for reductions in erosion and helped lead to near universal conservation tillage approaches in Western Canada. That influential report is nearly 40 years old and within that time yields of most crops have doubled and some have more than doubled.

It isn’t known just how much of that yield boom has come from tillage reduction and improved carbon sequestration, and how much has been derived from continual improvements in genetics and agronomy practices such as continuous cropping and precision agricultural technologies. The latter has masked the former when it comes to useful data.

The Senate is now taking another look at Canadian soils.

In hearings held so far, researchers suggest agriculture doesn’t fully understand soil.

If that is so, solutions that improve the net amount of carbon left behind in the soil after harvest would be equally poorly known.

Soil science is constantly improving, but the nature of soil is highly variable from acre to acre, between soil zones and agro-climatic locations and over latitudes that stretch from the American Heartland to the Arctic Circle. No single set of actions by producers will result in greater carbon efficiency.

As it sits now, any costs associated with improving sequestration of carbon in the soil come at farmers’ expense. There is no unified strategy to reward carbon retention nor is there a set of practices that might lead to it.

This makes it difficult to create a useful set of public policy carrots and sticks. Just saying no to tillage won’t work for many producers who have heavy soil and wetter climates or who grow certain crops that rely to some degree on tillage. Multiple wet or drought years will require strategies that won’t always align with a soil improvement plan that has short-term goals.

Changes in land tenure, with most farm growth taking place on rented ground, fail to foster long-term investments in land improvement. Compensation strategies have to reflect this reality.

A national soils directorate that ensures research across the country is properly funded and carried out would be a good first step. It could house a national soils database that would allow for greater use of remote sensing technologies as they relate to improved organic material and sequestered carbon.

It might even be a step the provinces and farmers would embrace.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen and Mike Raine collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.