Farmers concerned about how a wave of consolidation in the agricultural chemical sector will affect them, might soon see the trend spread to grain companies.

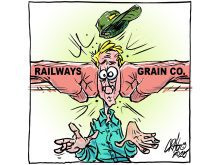

Glencore Agriculture Ltd., the giant commodity corporation’s joint venture that owns Viterra, last week made an informal approach to global grain trader Bunge Ltd. regarding a “possible consensual business combination.”

Bunge responded coolly, but the event sparked a wave of speculation about what might happen in the normally staid world of the world’s biggest grain traders.

Bunge and Archer Daniels Midland recently admitted publicly that they were struggling in an environment of oversupplied global markets that limit profit-making opportunities.

Read Also

Downturn in grain farm economics threatens to be long term

We might look back at this fall as the turning point in grain farm economics — the point where making money became really difficult.

More of the world’s farmers have storage and financing options to allow them to hold on to crops when prices are weak.

Grain users are in no mood to get into bidding wars that would lift prices and crop trader profits. Also, small players focused on organics, non-GMO and other niche areas are siphoning off business from the major players.

Business analysts say the sector is ripe for new partnerships or consolidation.

Bunge’s chief executive officer Soren Schroder recently spoke on the issue. “It is very clear that there are too many trying to do the same thing with a small margin. So there is need for consolidation…,” he said noting Bunge’s interest in partnerships.

We don’t know if Glencore’s approach to Bunge will succeed, but it would be an interesting partnership that would touch Canadian farmers in several ways.

Glencore bought Viterra, the company that grew out of the various mergers of the old grain co-ops, in 2012. To avoid competition concerns, it sold most of its agri products retail operations to Agrium and some grain elevators and processing operations to Richardson International.

Glencore, struggling from huge debt last year, sold 40 percent of Viterra to the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and 9.99 percent to the British Columbia Investment Management Corp. Its balance sheet has since improved.

Meanwhile, Bunge in 2002 acquired several oilseed crushing plants when it bought CanAmera Foods Ltd., which was once partly owned by Saskatchewan Wheat Pool and United Grain Growers.

In 2015, Bunge partnered with Saudi Agriculture and Livestock Investment Company (SALIC) to form G3 Global Grain Group and became the majority owner of G3 Canada, created from the assets of the former Canadian Wheat Board. In 2016, SALIC put more money in G3 Global Holdings, raising its ownership stake in the joint venture to 75 percent, leaving Bunge with 25 percent.

History buffs would note that a Glencore/Viterra-Bunge partnership would put the successor of the prairie wheat pools together with the successor of the CWB.

Would a Viterra-G3 partnership provide better competition to Richardson, Cargill, P&H and Paterson?

But the Canadian situation would be a sideshow to Glencore’s real goal: to move up the ranks to become a global ag player along with ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus, the so-called ABCDs of the grain fraternity. It would add a G to those initials.

Consolidation is a constant trend in agriculture — farmers do it themselves.

But farmers are suspicious of any consolidation in the companies they deal with.

They are already price takers with little market power.

Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen, Brian MacLeod, D’Arce McMillan and Michael Raine collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.