Our story last week about a mega farmer using bulldozers to convert thousands of Manitoba acres of pasture into cropland touched on a lot of hot button issues. It generated some healthy discussion across online forums.

Some wondered why this was a story. On the face of it, a piece about a farmer clearing land to grow more crops isn’t news. Several commentators took exception to The Western Producer, a farmers’ newspaper, making it so. Farmers big and small buy land and “improve” it all the time, although more people now question whether turning bush land or pasture into crop land is an improvement.

Read Also

Worrisome drop in grain prices

Prices had been softening for most of the previous month, but heading into the Labour Day long weekend, the price drops were startling.

The scale of the bush-clearing operation, the transformation of what was traditionally pasture into crops, the continued expansion of large-scale farming operations, and differing views on the sustainability of this changing land use all make this a matter of broader interest.

Questions also swirl around the impact on rural communities, as evidenced by a local petition opposing it.

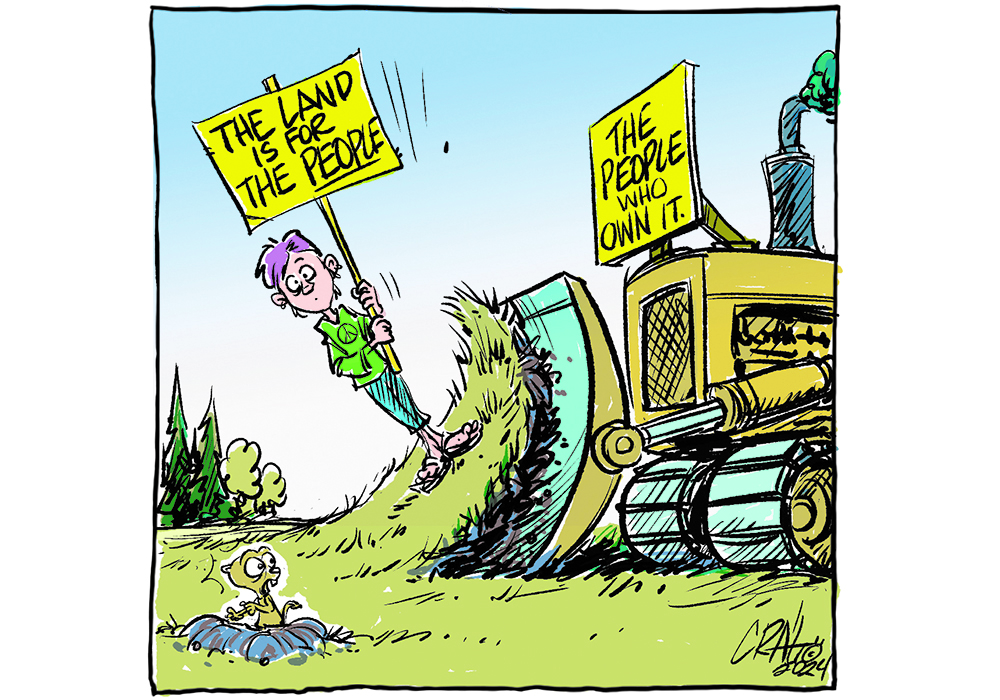

It is an interesting case study at a time when agriculture and society appear to be redefining the balance between private enterprise and public good, and when the focus of climate change mitigation strategy is shifting toward increasing biodiversity.

The consensus — at least outside agriculture — is that we need more trees and more natural land, not less.

Although some don’t like what they see, there is little by way of carrots and-or sticks to counter the economic drivers encouraging this development. Grain prices remain historically high. Cropland values, as tracked by Farm Credit Canada, continue to appreciate, often outpacing mutual fund investments.

Predictably, this prompts farmers to consider developing lower-priced land, which is occurring at about the same time that many cattle ranchers are looking to retire. Plus, moisture deficits in the southern Prairies encourage farmers to look north to areas that get more rain.

FCC has only recently begun tracking pastureland prices. Its data shows Manitoba prices rose by 19 per cent in 2023, followed by Saskatchewan at 12.7 per cent and Alberta at 9.6 per cent. Even with those increases, the cost of acquisition is a third to a half of what cropland costs.

Some fear history will repeat itself. Will we return to the 1930s, where vast swaths of marginal Prairie lands were threatened by desertification? We think not.

Farmers have access to better tools to support soil health than they had in the past. Precision-farming technology enables management and monitoring tailored to the needs of specific landscapes — provided farmers use it.

On the other hand, it remains to be seen whether these acres can deliver the productivity that justifies the inputs and management it will take to farm them. Some farmers find they make more money by farming less — removing low-potential lands from annual rotations.

Neither farmers nor government want to be in a place where landowners are prevented from managing their property as they see fit.

But because management of this landscape, much of which is privately owned, is of national interest, there are some important issues on the table for discussion. Farmers ignore them at our peril.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen, Michael Robin, Robin Booker and Laura Rance collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.