Uh-oh! China shut the border to Canadian canola.

What should a farmer do? Easy! Just don’t grow canola this year.

That’s what some people who don’t know much about real-world farming might think, after hearing that a third Canadian canola exporter has been told their license to ship to China has been yanked.

How should farmers in the Red River valley protect their much-tilled soils and deal with chronic problems with compaction, saturation and nutrient losses. Easy! Just go to zero-till like those farmers in Saskatchewan do.

Read Also

Trump’s tariffs take their toll on U.S. producers

U.S. farmers say Trump’s tariffs have been devastating for growers in that country.

That’s also something I’ve heard people say, some of them farmers from the west.

But of course the answers to vexing farming problems is never as easy as that. In the unique reality of each farm’s situation, pat answers really don’t do anything except annoy.

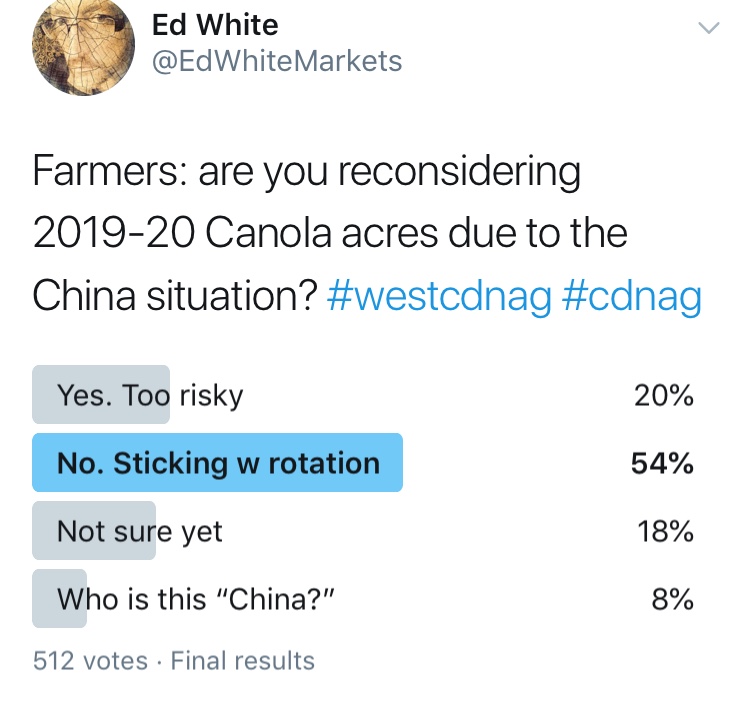

I ran a Twitter poll yesterday. I asked farmers if they were reconsidering canola acreage in light of China’s pressure campaign against Canada, which has targeted canola and caused prices to slump.

More than 50 percent said they were not intending to reduce acreage and were going to stick with their rotations. Only 20 percent said they were considering scaling-back

Why wouldn’t a farmer just plant something else? That’s what a couple of people have asked me in recent weeks.

Like what? That’s what I respond with. What could you swap-out canola for that would be demonstrably better in terms of market outlook and not ruin your carefully managed rotation? For most farmers, there are no easy substitutes to stick in canola’s place. Canola’s market outlook is a lot worse than it was a few weeks ago, but other crops mostly look poor too. And if you grow canola well, you aren’t going to be cavalier about abandoning it for something else that you might not feel as successful with. Crop-swapping is like market-timing with stocks: it’s very hard to do well, and usually you get suckered into trying it at exactly the wrong time. Most farmers have prepped their fields for their rotations, and few will make major changes in acres, methinks.

I was actually surprised 20 percent of farmers are reconsidering their canola acres, but most of them are probably thinking of marginal changes rather than wholesale switches. In the end, farmers will drop a few acres but rely upon producing a good crop and hoping the China crisis abates, or alternative markets are hungry enough to keep prices from collapsing.

Why don’t farmers in the Red River valley zero-till the way farmers out west do? That’s something I’ve heard numerous times from western farmers who see the tilled fields of eastern Manitoba, often with a tinge of condemnation to the question. Minimum tillage has been a moral imperative out in the west for years, and seeing tilled fields can outrage the righteous dryland farmer.

But down in the Red River valley things are different, and it’s not so easy to apply off-the-shelf systems from the west down here on the eastern Prairies. I’ve covered that reality for years, learning all about it after moving from Saskatchewan to Manitoba in 2001. It’s not so easy to do zero till when the soils are heavy clay, residue is thick as a shag carpet, the fields flood often, and much machinery is different.

Working through the ground-level realities is a complex challenge, and it takes a lot of brainpower and the challenging of assumptions. I saw a lot of that on Monday in St. Jean Baptiste, at the bottom and in the heart of the valley. A couple of hundred farmers and agronomists at the Red River Soil Health Summit put aside pre-seeding preparations to spend a day learning all about different methods being tried and applied to valley farming to get away from over tillage. Ideas from North Dakota and western Manitoba were bounced around, from controlled-traffic-farming to strip tillage to grassing wet spots. It’d be nice if big systems and easy engineering could just be applied to the farms down there, but real-world solutions to soil and crop management are likely to be developed differently on every farm, as each family finds the unique combination that addresses its challenges and opportunities.

Farming can seem simple to the outsider, but when you get down on the ground, the easy answers get strangled by the weeds of reality.