Many new digital tools are not adopted yet as farmers wait to see a return on investment from technology

The term precision ag has been around for decades, and like other terms ubiquitously used, it can be difficult to know what someone means when they say it.

To address this concern the board of the International Society for Precision Agriculture approved a definition of precision ag on June 20, which is as follows:

“Precision Agriculture is a management strategy that gathers, processes and analyzes temporal, spatial and individual data and combines it with other information to support management decisions according to estimated variability for improved resource use efficiency, productivity, quality, profitability and sustainability of agricultural production.”

Read Also

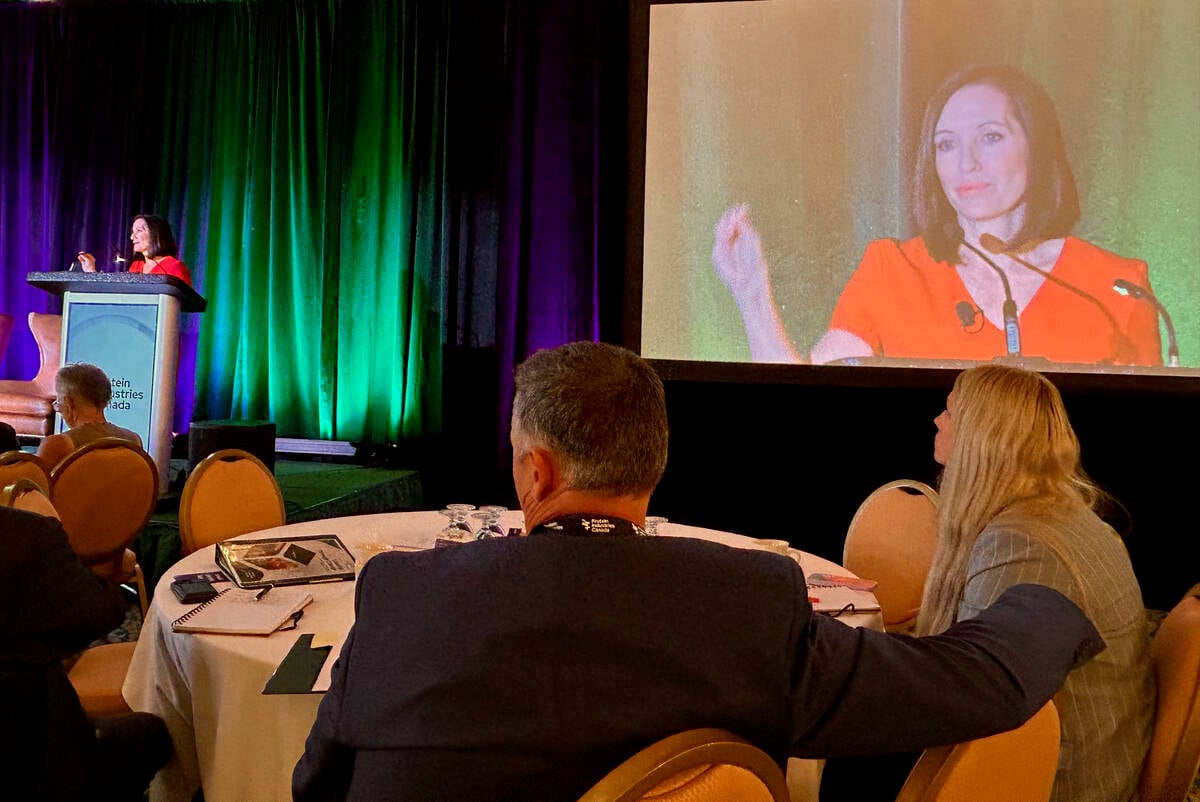

Canada told trade crisis solutions in its hands

Canadians and Canadian exporters need to accept that the old rules of trade are over, and open access to the U.S. market may also be over, says the chief financial correspondent for CTV News.

Alex Thomasson, professor in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering at Texas A&M University, helped work on the definition and he said most of the products developed for precision ag have failed to gain traction with farmers.

“I’ve been doing it for 22 years, which is most of the lifespan of precision ag, and really only a handful of technologies have been adopted in precision ag. Auto steer being one of the principle ones because everybody recognized the value of it when they see it,” Thomasson said.

“That and maybe one or two others depending on the region, but there is a lot of technology out there that had been really slow to pick up and it was because they don’t see the return on investment (ROI).”

Aside from some early adopters, which he said are critical to identify the advantages of new technologies, most farmers won’t bother with products within the precision ag realm until a ROI is clearly demonstrated.

He said the problem with some precision ag products is they don’t actually help growers answer questions and make decisions.

“The research community has not done an adequate job on focusing on key decisions that are made by growers that help them become more profitable, or help them mitigate risk better,” Thomasson said.

“When we begin to focus on these questions and how these new technologies influence the answer to those questions, we’ll begin to answer those questions and help them make those decisions more quickly.”

Part of the problem of researching precision ag is the many variables that have to be accounted for when deciding where, when and how much inputs to apply.

“My view is that agriculture is one of the most complicated businesses in the world,” Thomasson said. “There are variables from region to region, from year to year, from field to field, from one location in the field to another in terms of soil and topography, in terms of insect and weed and disease infestations. So it’s extremely difficult to know what questions to ask when you collect a lot of data.”

There has been lots of hype about drones in precision ag and much of Thomasson’s research has involved drones, but he said in most uses cases, drones do not provide adequate ROI to justify their use.

“The use of drones in field crops like grains and cotton, the return on investment hasn’t been shown yet. I think in the long run, potentially maybe. But it’s sort of the age-old precision ag question rearing its head again, where is the profit in this?” Thomasson said.

He said drones are being used in a commercially viable way in construction and mining and there are a few niche examples in agriculture especially in high-value crops like wine grapes where an expenditure can be justified.

He thinks of drones in these early stages as remote sensors similar to satellite data, where producers analyze the data to make decisions such as with prescription maps for applying inputs like fertilizer or insecticide.

“In many of the grain crops, the per-acre profitability is not high enough to justify the current cost of collecting image data with the drones. That may change down the road but I think that is the way it is right now,” Thomasson said.

A precision ag technology Thomasson said will soon have a big impact on agriculture are extremely precise sprayers.

Spraying used to be done uniformly across the field, until section-by-section spray control, enabled by precision ag, came along and avoided overlaps.

“Over time, I think we will be able to see more nozzle by nozzle spray control and we will also probably have real-time sensing drive what these nozzles are doing. As opposed to developing a map in advance,” Thomasson said.

Easy-to-understand profitability maps of fields will also help growers improve their growing techniques.

“When growers begin to see green for dollar signs on one part of the field and red for losing money on another part of the field, and if they see that on a repeated bases that will make them aware there are big changes that they could potentially make to either make more money or lose less money,” he said.

Similar to the internet of things (IOT), Thomasson said the internet of agriculture (IOA) refers to how a lot of farm equipment has sensors that collect data that is commonly pushed to the cloud where analysis can be run with artificial intelligence algorithms that derive useful or actionable information from the data.

However, before IOA really gets its footing in broad-acre grain production wireless connectivity needs to be improved.

“So even if you have sensing capability and wireless on your tractor or harvester, you can’t push that data to the cloud until maybe you get back to the farm base. There are a lot of issues waiting to get resolved before we can take advantage of these technologies,” he said.

Thomasson participated in The Identifying Obstacles to Applying Big Data in Agriculture Conference in Houston in August 2018, which among other things identified obstacles that need to be addressed before big data can be more broadly used for in-season real-time decision making.

Beyond poor rural broad-band, further obstacles include a lack of data interoperability between the various software systems on farms, farmer-sourced data such as combine yield data are often not backed-up by ground truth data, unclear ROI, and a lack of growth models tied to actual soil properties.