Dan Mazier thinks it’s high time that rural digital infrastructure be treated as an essential service, much like landline telephone service.

“It’s a mandatory utility and it’s no different than water, it’s no different than electricity. It’s one of those utilities that we now need to function as a Canadian,” said the president of Keystone Agricultural Producers in Manitoba.

“Let’s provide that to rural Canadians and let’s get on with the plan.”

Mazier was part of an agricultural panel that met with a federal finance committee last fall about sustaining rural communities. He and other farm leaders advocated for more rural electronic infrastructure that is fast, reliable and accessible.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“Everyone says it will cost millions and millions of dollars. I say so what? They did it with the telephone lines before. They did it with electricity. They’ve done it in Sask-atchewan and Alberta with (natural gas) pipelines. Why can’t we do it with digital infrastructure?” he said.

“If we had taken the same ap-proach with our electricity or with our water, rural Canada would look a lot different,” he said.

Lack of access to reliable high speed internet service is hurting economic growth in rural and remote areas, which creates a have-not situation in terms of the ability to attract business.

Frustrated farmers, rural businesses and homeowners have said they have inadequate and expensive internet service. Being digitally connected is now considered an essential service in towns and villages for commerce and quality of life, Mazier said.

The adoption of precision agriculture telemetry systems has left some farmers stranded in their fields in areas with a weak signal or no signal at all. And for some producers without reliable data, the age of autonomous machines is stalled.

However, that could soon change with recent announcements of internet infrastructure and up-grades.

In December, the federal government said it would include $500 million in its 2016-17 budget to improve rural internet service across Canada.

“By increasing access to high-speed internet, the Connect to Innovate program enhances our rural and remote communities’ ability to innovate, participate in the digital economy and create jobs for middle-class families,” Innovation, Science and Economic Development Minister Navdeep Bains said in a news release.

The five-year investment is earmarked to improve service in 300 rural and remote communities.

The money will be used to build what the government calls high capacity “backbone” networks to transport digital information or upgrade existing networks.

Bains said rural residents and institutions will see a dramatic change in internet speeds when the networks are installed.

“Backbone networks are the digital highways that move data in and out of communities,” he said.

Coming on the heels of the federal government’s funding an-nouncement, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission declared broadband internet access a basic service for all Canadians, just like landline telephone service.

“Access to broadband internet service is vital and a basic telecommunication service all Canadians are entitled to receive,” CRTC chair Jean-Pieere Blais said in a news release.

The CRTC said the aim is to ensure internet service providers offer services at speeds of at least 50 megabits per second for downloading data and 10 Mbps for uploads.

It said about 82 percent of households and businesses currently receive that level of service, but it wants that increased to 90 percent by 2021 and 100 percent within 15 years.

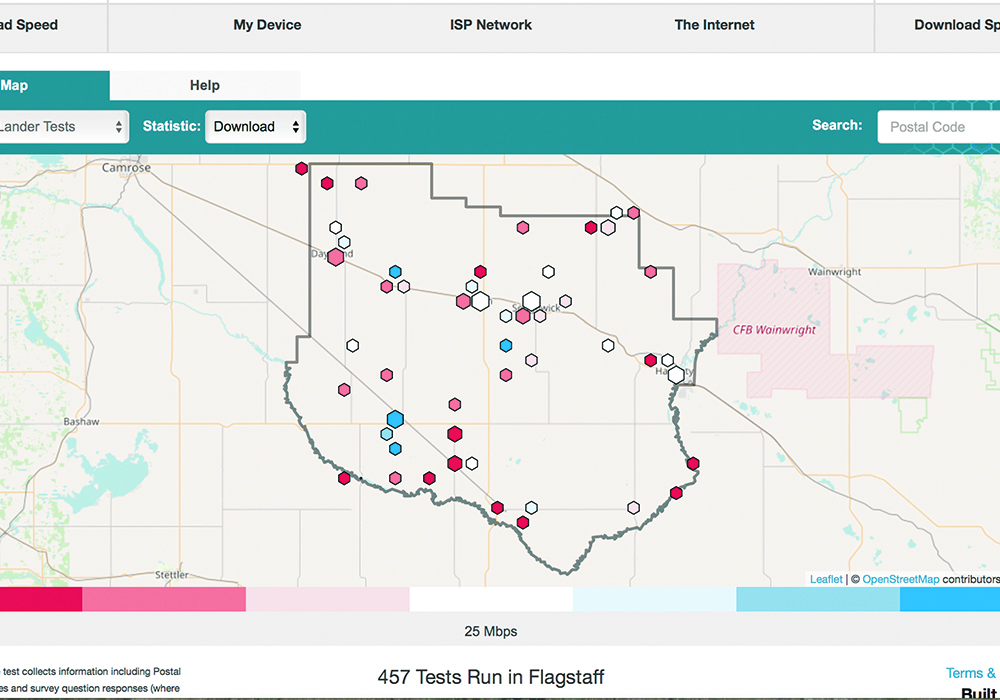

However, Lynn Jacobson, president of Alberta Federation of Agriculture, said these numbers do not accurately reflect the rural reality.

“It might average out to that with the urban, but when you’re talking rural, no we don’t get that,” he said.

“They might not be using the right comparisons and be lumping in our smaller population with the larger population, which doesn’t give a true picture of what’s happening in rural Canada.”

The CRTC said internet service providers will also be required to offer unlimited data options for fixed broadband services.

Mobile wireless service should also be made available to all households and businesses throughout Canada, as well as along all major Canadian roads.

However, the CRTC said that ensuring everyone in the country has broadband service will cost billions of dollars.

The gap between urban and rural internet services and fees rang loud and clear for Ron Bonnett, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture. He farms near the community of Bruce Mines, Ont.

Bonnett’s grandchildren from Barry, Ont., visited him for a week last summer, and they connected to his wireless internet over the phone with his limited data plan to stream movies and play games.

“Our bill went from $110 to almost $600 for that week that they were here,” he said.

“That was an expensive education. That’s one of the problems that you learn between the rural and urban communities. We don’t have the ability to get an unlimited data plan.

“I can’t blame the kids. They just took it for granted. They do it at home (in Barry) all the time. It’s just part of life for them.”

“I think a number of people in urban communities wouldn’t realize how much that is actually used now in agriculture.”

Jacobson agreed that rural Canadians tend to pay more for internet services.

He farms near Enchant, Alta., and said some rural areas have good wi-fi, but the internet speed for those on a VHF (very high frequency) system with a radio tower have less than half the speed of a wired system.

“You’re barely above streaming capacity. If something happens on your system a little bit, then you’re down and you’re waiting again. It’s not as bad as the old dial-up but it’s not great,” he said.

He said a decreasing rural population translates into less competition between service providers.

“In Lethbridge, it will cost you $30 to have wi-fi. To get the same service out in the country will cost you $95 to $100,” he said.

“We’re paying a minimum double of what they’re paying in the city for the same service.”

Mazier said it’s also an issue of synchronization of responsibilities between governments and service providers. He said in Manitoba, fibre optic cable is provided only to rural municipalities, schools, hospitals and other essential services.

“They would not allow any of the rural residents. If it went by your door you weren’t hooking on.”

As part of the federal funding decision, telecommunication firms will have access to a $750 million, industry-sponsored fund over the next five years to invest in broadband infrastructure.

The first $100 million will come from a fund that subsidizes telephone services in isolated regions, but telecommunications companies will have to guarantee a set price for service. However, there is no cap on what internet service providers can charge for basic broadband internet.

Blais said industry and governments will have to take part in filling the service gaps that exist across the country, which impacts about two million people.

The CRTC also ruled that internet service providers have six months to provide customers with contracts that outline the services being provided, usage limits, minimum monthly charges and the full cost of data coverage.

“I think it’s a start but what might make more impact even is the CRTC coming out and basically saying Canadian households have to be connected because they have some teeth that they can mandate some of the providers,” said Bonnett.