La Ninas have historically been tough on Argentina, but the impact isn’t expected to be as bad this time

Weather watchers are leaning toward predictions for a La Nina developing this winter and that has ramifications for crop production around the world.

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology said there is a 70 percent chance or triple the normal likelihood of La Nina occurring.

The Climate Prediction Center in the United States predicts a 65 to 70 percent chance of a weak La Nina continuing through fall and winter until February to April of 2018.

Drew Lerner, president of World Weather Inc., said La Nina’s influence is felt long before it is officially declared to exist.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“As far as I’m concerned, the period from when La Nina first begins to evolve to the point of its maturation is the most influential period on global weather and we are in the midst of that right now,” he said.

The biggest impact for world agriculture is in South America.

Argentina tends to have a dry early spring and that is already happening in a country that is the world’s third largest exporter of corn and soybeans.

“The thing that the marketplace remembers really well right now is the last two La Nina events were pretty tough on Argentina,” said Lerner.

That is because the country was already in a dry weather pattern heading into those two events. That is not the case this year.

“The impact on Argentina will most likely be less than the last two events,” he said.

Lerner said the early corn and sunflower crops will suffer most. The late corn and soybean crops are typically spared because by late summer or early spring the dryness tends to shift to the east of the country, outside the main production areas.

Brazil’s crop production typically benefits from La Nina, although the start of seasonal rains is usually delayed, which is what has happened in October and early November.

But by midsummer, in January and February, it tends to become wet in some of the main corn and soybean production areas stretching from Mato Grosso to Sao Paulo.

The only areas of the country that are usually dry are the extreme south in Rio Grande do Sul and the northeast.

David Streit, co-founder of Commodity Weather Group, said the markets are getting nervous about the dryness in Argentina but it will have to be a strong event to generate much of a price rally.

“With so much surplus in the world right now I don’t think you’ll ever get just an Argentine issue to really push the market hard, but the market will pay attention to it,” he said.

Streit said most of the damage will happen during the pollination phase of corn and soybean production in the December through February period.

The wheat crop is already heading, so it will likely avoid any major damage.

“I don’t think we’ll get it dry enough, fast enough to impact the (wheat) crop,” he said.

Another region he will be watching is eastern Australia, which tends to get quite wet in La Nina years. There is rain in the forecast there over the next couple of weeks, which could damage wheat and canola quality.

India tends to have a wetter bias during its rabi or winter crop season, which would be beneficial for chickpea and lentil production.

North Africa and the Middle East tend to be dry, especially Morocco and Algeria, which are big producers and importers of durum. Turkey, which is a major producer and importer of lentils, will also be dry.

Indonesia and Malaysia will have a wet bias, which could mean increased palm oil production.

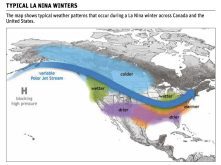

Winter precipitation is often below normal in the southern U.S. and above normal in the northern Plains, Pacific Northwest and into Alberta and Saskatchewan.

If La Nina is still around by spring and summer, it will likely lead to below normal precipitation and above normal heat in the U.S. Midwest and into portions of Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan.

If it is strong and persistent enough, it could lead to drought in the U.S. corn belt.