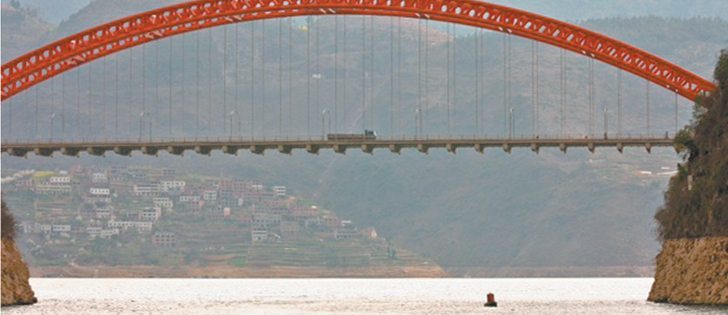

New farming practices in an ancient land | Construction of the massive Three Gorges Dam in China’s Hubei province moved more than a million people and changed the farming landscape of the region forever. | Story & photos by Barb Glen

YICHANG, China — Tsui Yong remembers his mother’s sorrow when the rising waters of the Yangtze River reservoir swallowed her orange trees.

In another two months, she would have harvested and sold the oranges for which this region of the Hubei province is known.

The reservoir created from completion of the massive Three Gorges Dam, which began operations in 2003, covered 632 sq. kilometres of land, including more than 60,000 acres of farmland, two cities, 11 counties and 116 towns.

Yong’s parents were among the 1.39 million people who had to relocate.

Read Also

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

“For me, it’s O.K., but my parents (were) affected,” said Yong, who works as a tour guide at the dam site in Yichang.

“Some of their farmlands (have) been flooded. My parents, they built a new house by the new highway. Actually, people in this mountainous area like to build their new house near the new highway because it’s convenient for transportation.”

The Three Gorges Dam, so named for the Qutang, Wu and Xiling Gorges that feed into it, was controversial from its initiation 30 years ago, but Yong’s presentation to tourists emphasizes the positive aspects.

He talks about the new houses provided by the government and the job opportunities created when industries were encouraged to relocate near the dam and reservoir, closer to needed resources.

In the immediate area around the dam are new factories making orange juice, shoes, solar heaters and clothing.

“Young people even some feel good because young people can quickly adapt to a change environment. They got more opportunities. But not everybody (is) like that,” he said.

“Everything is changing. It’s still better than before.”

According to explanatory dam data sold to tourists at the site, relocation costs made up almost half the project’s total budget.

“It is because of those ordinary Chinese people committing to their obligations that the resettlement and the construction of the TGP (Three Gorges Project) can proceed successfully,” it reads.

Yong said compensation was provided to those who lost homes and property. The amount was based on the type of structure. Those with concrete foundations received more than those with an earthen base, for example. In the case of orange trees, amounts varied with the size of the tree.

Those who had to move were given a choice of going to higher ground on the reservoir side, which is mountainous, or to lower and less hilly ground below the dam.

Oranges and tangerines were primary crops for many upstream, so moving below the dam sometimes required them to learn new agricultural skills to grow the rice, wheat and cotton more suitable to that region, said Yong.

In some cases, entire villages were moved so communities could be retained. Some chose to relocate to cities, including Shanghai, far downstream, or Chongqing, 650 km upstream.

It was part of the urban migration that continues today in China, with young people moving to cities for more plentiful and better paying jobs.

The main purpose of the dam is flood control, Yong said. More than 15 million people live in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze and history shows damaging floods occur about every 10 years.

He said floods in 1931 and 1935 killed 280,000 people downstream and another flood in 1998 killed 1,300. Losses in the latter flood were valued at $26 billion, almost as much as the entire cost of Three Gorges Dam construction at $28 billion.

“So just only considering the function for flooding control, it’s worth it,” said Yong.

However, the hydroelectric capacity of the dam is also significant in this developing country of 1.3 billion people where 70 percent of the electricity is still generated from coal.

The dam has an installed electrical generation capacity of 18,200 megawatts, according to dam site data. It has 32 turbines of 700 megawatts each, with 1,000 cubic metres per second flowing over each turbine at peak flow.

Yong said average annual power generation is 100 billion Kw hours, making it the largest power plant in the world. The electricity is distributed within a 1,000 km radius of the dam.

Even so, the dam provides only three percent of China’s electrical needs, according to Yong, and the percentage is dropping as more electricity is needed for factories and an improved lifestyle that includes more appliances and electronics.

In the 1980s, Yong said few people in his hometown had a television. The nearest one was a 15 minute walk away, and was made more or less public by its owner. His parents bought their first television in 1992 and now they are common in most homes, along with washing machines and air conditioners.

The ever-growing need for electrical power has prompted four more dam projects on Yangtze tributaries, said Yong.

He had no information on potential irrigation and food production benefits provided by the dam, and English translations of dam data are also silent on that issue.

However, transport of goods is another benefit of the dam and the water level regulation it provides. Numerous cargo ships ply Yangtze waters.

The dam has two, five-stage locks that allow ships to navigate the 113 metre change in water level above and below the dam. Passage through the locks is free and takes about four hours.

A ship elevator, designed to lift ships, cargo and water using a system of cables and gears, remains under construction, slated for completion in about three years.

About 35,000 people worked on the dam at peak construction, said Yong, and about 2,000 remain there to operate it and do ongoing work.

The dam spans 2.3 km across the Yangtze. Permanent gantry cranes along its top control the gates on the spillway.

River levels can now reach 175 metres in depth and did reach that level in 2010, although they are lower now.

This particular location was chosen because of granite geology that provides a suitable foundation. As well, there was a natural island in the river at this point, which allowed one side to be used as a diversion channel while construction went ahead on the other. That eliminated the need for diversion tunnels, Yong said.

Three Gorges is neither the largest dam in the world nor does it have the largest reservoir, Yong said.

However, its world records include largest power generation, at 10 billion kW hours per year, and largest concrete dam, at 28 million cubic metres. It is solid concrete as opposed to rock or earth filled.

Three Gorges will also have the largest lift lock, when that phase is completed, and already has the largest inland lock system.

“Some dams have only one function, but this one has many benefits,” said Yong.

In his award-winning 2007 documentary titled Up the Yangtze, filmmaker Yung Chang asks viewers to “imagine the Grand Canyon being turned into a great lake.”

Storage capacity of the Three Gorges reservoir is 3.93 billion cubic metres and it is indeed a big lake, some of it with 3,000 years of history beneath it.