Canada’s wheat exports have been sluggish this year because of a poor quality crop and stiff competition from other regions, say analysts.

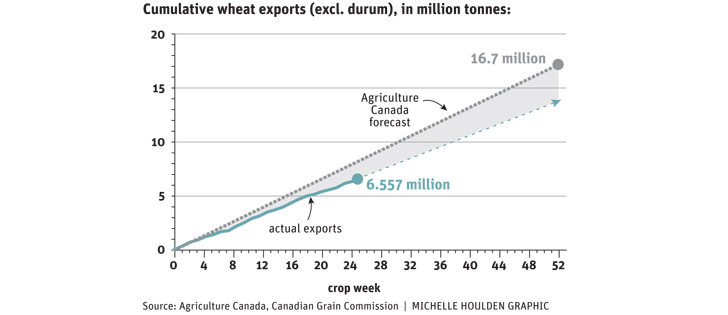

Exporters shipped 6.6 million tonnes through week 25 of the 2016-17 campaign compared to 8.1 million tonnes a year earlier.

The opposite scenario is unfolding south of the border where U.S. wheat exports were 15.39 million tonnes as of Jan. 19, up from 11.96 million tonnes the same time a year ago.

John Duvenaud, analyst with Wild Oats Grain Market Advisory, said it was Canadian wheat that was flying out the door last year while U.S. farmers were sitting on their wheat because of lackluster prices.

Read Also

Huge Black Sea flax crop to provide stiff competition

Russia and Kazakhstan harvested huge flax crops and will be providing stiff competition in China and the EU.

The difference this year is that the Canadian crop is in bad shape. He estimated that half of the durum crop is feed quality along with a sizeable portion of the spring wheat crop.

“The wheat is trapped here because it’s feed wheat and it’s going to have to move domestically because that’s the only market that’s paying for it,” said Duvenaud.

He does not think farmers will be willing to hold onto their feed wheat into the new crop year.

“I see pressure on the feed market right through until next summer,” he said.

Duvenaud believes 90 percent of the good quality milling wheat will be gone by the time the new crop year begins.

Neil Townsend, senior market analyst with FarmLink Marketing Solutions, has a different take on the situation. He said Canada’s poor export performance is the direct result of having to compete with big crops in places like Russia, Ukraine, Australia and Argentina.

“Just globally there is a lot of wheat around and buyers have lots of choices,” he said.

“Canada is at a disadvantage (due to) all the usual suspects like geography, ocean freight and internal logistics.”

Other factors to the slow start to the export program were the late harvest and the relatively low carry-in stocks of four million tonnes, down from six million tonnes the previous year.

And then there were the quality concerns.

“The perception of the crop was fairly negative for a fairly long time in terms of the quality distribution. That probably slowed down sales for a little while,” said Townsend.

He believes the quality turned out better than expected, but the buyer hesitation created a window of opportunity for other exporters such as the European Union.

The EU did not have a huge crop, but the euro has been gaining strength against the U.S. dollar in recent weeks, creating an incentive to export the crop rather than consume it domestically.

The United States harvested a large spring wheat crop, which is making it an opportunistic buyer of Canadian wheat. U.S. spring wheat is also competing with Canadian wheat in places such as Mexico and other Latin American countries.

“We’re getting it from a lot of different sides in terms of the competition,” said Townsend.

The fiercest competition is from Russian wheat. Russia produced 72.5 million tonnes of the crop, up 11.5 million tonnes or 19 percent over the previous year.

“They have a big segment of wheat that has got good milling attributes,” said Townsend.

“It’s an old idea to think Canada just has this special type of wheat that everybody prefers.”

Agriculture Canada is forecasting Canada will export 16.7 million tonnes of wheat, down 485,000 tonnes from the previous year.

Townsend thinks that will be hard to achieve given that exporters are already 1.56 million tonnes below last year’s pace and they haven’t even hit the halfway point of the marketing campaign.

He thinks Canada will continue to struggle, and exports could end the year 1.9 million tonnes below last year.

Townsend is not forecasting a repeat of last year when wheat exports made up a lot of ground in the second half of the campaign.

The main reason for his pessimism is the stiff competition from Australia, where growers recently harvested a record 33 million tonnes of wheat, up from 24.5 million tonnes the previous year.

That is a 35 percent bigger wheat crop that they have to sell, and the Aussies are aggressive marketers of the crop.

“They just don’t sit around and look at their wheat,” he said.

“They get it going and get it moving.”

As a result, there is a good chance Canada will end up with much more than the 3.5 million tonnes of carry-out that Agriculture Canada is forecasting. Townsend thinks it will be closer to five million tonnes.

It is still not an overly burdensome carry-out, which is why he is forecasting wheat seeded area will remain flat at 18.4 million acres next year. Some growers may give up on the crop, but he believes spring wheat will steal acres from durum.

Duvenaud thinks durum acres will be down 40 percent and spring wheat will fall by 15 percent compared to 2016. Peas and lentils will pick up those lost acres.

Townsend believes wheat will continue to lose ground to competing crops such as canola and pulses in the long-run because while demand for those crops is growing because of changing tastes, the only thing wheat has going for it is the ever-expanding global population.

Farmers are also getting increasingly tired of growing wheat.

“One thing that’s super-frustrating for the Canadian farmer is all the quality parameters of wheat and the struggle with the expansion of disease,” he said.