WATROUS, Sask. — Nancy Johns and her husband, Jason, have deep family roots in agriculture.

And if Nancy’s suspicions are accurate, those roots might soon extend to another generation in the Johns family tree.

The Johnses live in Watrous and manage a century-old family farm near Zelma, 40 kilometres away.

Jason’s parents still live on the farm and Jason and Nancy share the work.

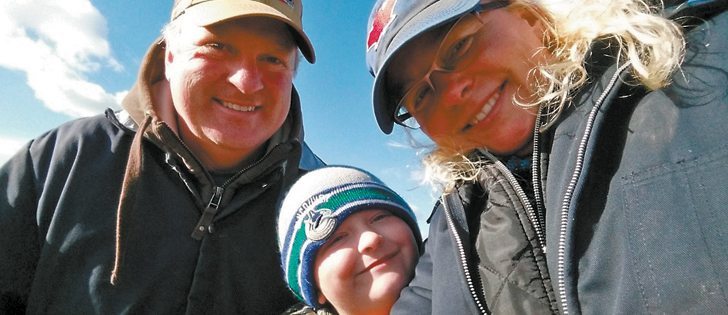

The Johns’ son, eight-year-old Ben, has all the makings of a next-generation farmer.

When he’s not in school, Ben spends every spare minute with his mother, walking fields, scouting for insects, riding in farm machines and learning the art of growing and harvesting crops.

Read Also

Students urged to consider veterinary medicine

Alberta government makes $86.5 million investment in University of Calgary to double capacity for its veterinary medicine program to address labour shortages in the field.

“He’s my little sidekick,” said Nancy, who works on the farm, helps with management and runs her own independent agronomy business on the side.

“He loves farming and he lives in the combine. It (farming) is his heritage. He’s grown up around it and when he gets older, it will probably be his thing.”

Johns’ interest in farming followed a similar course.

She grew up on a mixed farm near Silton, Sask., and her parents and brother, Scott, and his family still farm in the area.

Johns left the farm after high school, got a degree in agriculture and eventually landed in Watrous, where she worked as an extension agrologist with Saskatchewan Agriculture.

In 2005, the Saskatchewan government closed 22 rural service centres and laid off 120 people in communities around the province, including Watrous.

That’s when Johns started her own agronomy business called Hope Floats Agronomy.

Local clients appreciate the fact that Hope Floats is not affiliated with crop input retailers.

The advice she gives is independent and non-biased with no hidden sales agenda.

“I’m not tied with any company, so I think that really helps,” she said.

Johns admitted that farming, raising a son and running an agron-omy business can be a handful at times.

Farming can be a stressful career even at the best of times, but the lifestyle is rewarding and the financial returns have been good during the past few years.

“And it’s a good life, generally, as long as you can handle the stress,” she said. “That’s one part of farming that a lot of people don’t think about is the stress … and being able to have the faith that the crops you plant will end up in the bin.”

Her agronomy background has helped keep the farm profitable.

Good crop management practices combined with sustainable rotations are central to the operation’s success.

The Johnses plant 5,500 acres each year, producing wheat, malting barley, canola, flax, peas, lentils and the odd crop of fababeans.

Johns has also sat on the Sask-atchewan Flax Development Commission’s board of directors for the past four years.

The experience with SaskFlax has widened her perspective and given her new insights into the issues that affect production, marketing, processing and use of flax.

“It’s a big time commitment, I’m not going to lie,” she said.

“But you really get to see the industry more as a whole. As a farmer, we produce flax, we sell it and we (complain) when the prices are too low.

“But when you start looking beyond production, to where we’re marketing the crop and at some of the environmental factors … it really gives you a different perspective.

“For example, I’ve learned a lot more about the end user and about the importance of having consistent products going out.”

Johns sees a positive future for flax production and prairie agriculture in general, but she ack-nowledged that there will be challenges.

The real and perceived competition for land has pushed values and rents to new heights in recent years, which has made it harder for young farmers to get into the business and remain competitive.

“Young guys who are starting out … can’t walk in and drop a $1million, $3 million, $5 million, and I don’t think it should be up to (the parents) to put their retirement on the line just so their kids can farm,” she said. “But when you’re trying to buy land and you’re going up against investment funds and other corporate investors, you just can’t compete for one or two quarters against that.”