DELBURNE, Alta. — Klein Farm, situated in the rolling parkland of central Alberta, keeps its eggs in several baskets.

The farm includes a free-range poultry operation numbering 300 turkeys and 2,000 chickens, a 20-acre orchard planted with rows of black currants, saskatoons and chokecherries, and 900-plus acres of commercial grain: wheat, malting barley and canola.

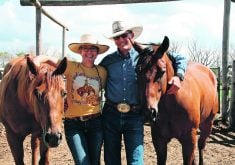

Emery Klein operates his third-generation farm with help from his parents, Elmer and Victoria, his four teenaged children, and Elmer’s brother, Pat.

Klein hopes some of his kids will carry on the farm. The younger three are still in school while Ethan, 19, is working as an agricultural technician apprentice at a nearby John Deere dealership.

Read Also

Accurate accounting, inventory records are important

Maintaining detailed accounting and inventory records is not just a best practice; it’s a critical component of financial health, operational efficiency and compliance with programs like AgriStability.

The grain has been a mainstay on the farm since Klein’s grandparents started farming in the early 1950s. Before this, they had been running a general store at Nevis, about 30 kilometres northeast of Delburne, which they swapped with Klein’s Great Uncle Frank who developed allergies to farming.

Klein works off-farm as a millwright at a nearby sour gas plant. Numerous seasonal jobs there and at the farm often overlap, which makes time management crucial.

His cellphone with calendar is always close at hand.

“I could not farm without my smart phone,” Klein said.

Klein’s father Elmer tends to the fruit trees, Victoria is mostly retired but runs errands, Uncle Pat drives tractor in spring and combine in fall and the kids help with a variety of jobs.

Help is hired at key busy times, such as when the orchard berries ripen and need processing.

Victoria encouraged the family to start the orchard in the late 1990s, which started with black currants. The chokecherries were added initially as a windbreak for the currants. The saskatoons came later.

“We love the orchard,” said Klein. “It’s a part of the farm that’s very soothing.”

While the market for berries has waxed and waned over the years, the demand is strengthening.

The Kleins sell at the farmgate and through farmers markets in central Alberta.

Klein also gets requests from chefs, bakers and wineries for products.

“I have one winery who wants one particular variety of currant and he’ll buy everything I produce.”

Since the saskatoons are in varying stages of production, he buys from other berry producers to fill demand. A 53-foot refrigeration trailer is on site, where berries are cleaned, graded and frozen.

A short distance away, Klein has started digging the ground where the family plans to build a permanent berry processing centre, which is expected to be complete within two to three years.

At the time the orchard started, the Kleins wanted to further diversify. They lacked the land base for cattle and Klein wasn’t interested in hogs, so the family bought chickens. Initially they had laying hens and sold the eggs, but they later switched to strictly meat birds.

“It slowly grew,” said Klein.

“Now I’m capped due to the quota system”.

In addition to full birds, the family sells pieces, ground chicken and a variety of chicken sausages.

Some are unusual flavours such as saskatoon chicken, apple cinnamon, maple and rosemary garlic. The ideas for new flavours come from myriad sources.

“Everybody from family to employees to customers make suggestions to ‘try this, try that,’ ”said Klein.

He’s considering using dried and chipped trim from the orchard for flavoured smoke.

Klein sold out his turkeys this Thanksgiving and expects the same for Christmas. The fall turkeys average 15 pounds, while the winter birds are 20 lb. or more.

The birds are free range, where they can scratch the dirt, eat green grass and insects, and breathe fresh air. Their foraging diet is supplemented twice a day with ground wheat. The birds are not medicated and do not receive hormones or fed animal byproducts.

One downside of free range is evidenced by a few white feathers outside the fenced pasture. Predator losses are minimized by the use of electric fences and self-charging, flashing LED lights.

Klein said the pros to free range, non-medicated birds outweigh the cons.

“I have more losses, but a cleaner, better tasting product. It’s a niche market.”