Shortages of everything from food to fuel and even paper meant the nation’s homes had to do with less

Rationing was in effect during both the First and Second World Wars, making it hard to obtain sugar, butter, eggs and other scarce food items that were needed to help feed the men fighting overseas.

“For five long years during the Second World War and beyond, consumption of sugar, meat and dairy products was restricted in Canada, but we didn’t complain. Not only were we feeding the desperate British population, but also our fighting servicemen overseas, prisoners of war and starving refugees,” writes Western Canadian author Eleanor Florence. She has written several books and a regular column that often feature the war years experience, including Bird’s Eye View, her novel about a young Canadian woman who joined the Canadian air force in the Second World War.

People got creative to stretch their rations by planting what were called Victory Gardens. Gardening became the new trend in cities and farms including community gardens.

Interest in hunting and fishing increased to stretch their meat allocation.

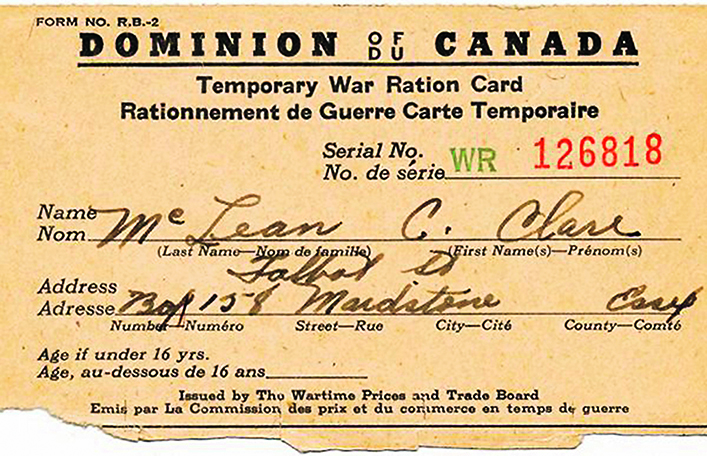

Eleven million ration cards were issued in Canada. Inside were coupons for butter, sugar, and meat. For the first few years, from 1939 to 1941, Canadians were willing volunteers but as the war dragged on, people started to get weary of going without. The government began a co-ordinated ration program in January 1942 beginning with gasoline. Over the next year, sugar, coffee, tea, butter and meat were also rationed.

Canadians may have grumbled about food shortages, but on the whole they were willing participants. Australia, New Zealand, and the United States also had rationing.

There was massive sympathy for the beleaguered British people, who were far worse off. Britain was fighting for its life, and everyone knew it. In Britain, rationing began in 1940 and didn’t end until 1954.

Today, we eat such a great assortment of imported foods that we don’t think of them as exotic but during the war, importing food became difficult as many merchant ships were taken over by the military, and many others were sunk by German submarines.

Even the most basic foods we produce here were restricted: bacon, steak, pork chops, butter, cheese and ice cream. You ate what you could prepare and cook at home, and often grow yourself.

Here are the weekly rations per adult:

- sugar: one cup (the average Canadian eats twice that much today)

- tea: two ounces, or coffee: eight ounces. (because these items came from other countries)

- butter: four ounces (one-quarter pound)

- meat: 24-32 ounces (less than five ounces per day)

- beer, spirits and wine were also rationed, the amount varying between provinces

Canadian culinary historian Mary F. Williamson of York University, Toronto, quoted her mother’s letter written in September 1942: “We are asked not to use any pork or bacon for seven weeks while our commitments to Britain are being filled, there is no beef at all for sale, the sheep raisers are asked not to slaughter in order to raise more badly-needed wool, so a great many butchers have shut up shop.”

Because meat was scarce, a food item was invented that was found on almost every table during and after the war. A processed meat product called Spam appeared on grocery shelves, and people ate it up.

Lower-income families were already accustomed to “making do” and eating a plain diet, so it was the middle-income and upper-income families who felt the greatest loss of luxury food items. City dwellers had it worse than people in the country.

Whenever possible, people picked wild berries along roadsides. An extra “canning ration” of 10 pounds of sugar enabled home preserving to stretch food rations by canning and pickling of garden and wild-picked produce.

Imagine going into a store today and not finding a single pre-packaged, pre-prepared item. Everything had to be peeled and chopped and made from scratch. Women with jobs must have found this especially demanding. Not only that, but having a ration card didn’t guarantee those items would be available.

According to Mary Williamson’s mother, by Christmas 1943 food was in short supply.

“Christmas dinner will be simple. All the festive additives are either not to be had, or are only obtained by hours of journeying from shop to shop and standing in line here there and everywhere.”

Was the rationed diet healthy? Opinion is divided on that question. There wasn’t much protein and some available foods were starchy. In fact, the Canada Food Guide was created in 1942 as a response to concerns that people may be malnourished.

On the other hand, people ate about half as much food overall, so obesity wasn’t a problem and neither was getting your eight servings of vegetables every day.

As meat became more difficult to find, root vegetables became a staple part of everyone’s diet. In England alone, production of potatoes went from five million to 10 million pounds. Turnips were also found on the wartime menu. “Glazed turnips” was a dish designed to dress up a serving of turnips.

Goods such as rubber, gas, metal and nylon were also hard to come by because they were needed for the war effort. A scrap metal drive encouraged people to donate old cookware, old appliances and other household items.

Nylon stockings had just been invented in 1939 as a better choice over silk stockings but in 1940 all stocking production ceased because the nylon was needed for parachutes. Cosmetic companies came up with leg makeup and women began painting their legs a tan colour with a brown line down the back to look like the classic seams of stockings.

The government also controlled many other items such as new household appliances and automobile tires. Posters and radio ads advised, “Use it Up, Wear it Out, Make it Do, or Do Without.”

In other cases, there were limits on what could be made and sold. This included clothing, which could only be made in certain styles, or with certain fabrics. These limits helped free up more materials and manufacturing capacity for wartime needs.

When the war ended in 1945, people were happy, not only that their men and women were home, but it meant another step closer to the return of normal life.

Rationing didn’t end as suddenly as the war because Britain remained in a desperate situation immediately following the war and refugees needed help. In Canada, rationing ended in 1947.

Research for this story:

Canada and the First World War – Canadian War Museum

Wartime rations meant Canadian cooks got creative – Elinor Florence, elinorflorence.com.