Phosphorus imbalance can wreak death by starvation or death by poison, which means proper balance is critical

It’s a dilemma of too little and too much simultaneously.

The Earth has a finite volume of rock phosphate for fertilizer. Yet, too much phosphorus flows toxic in our waterways.

“We face a phosphorus paradox. Too little phosphorus threatens our food security. Too much phosphorus is a major cause of water-quality impairment worldwide,” said Helen Jarvie, a scientist with the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in the United Kingdom.

The week starting Sept. 15 has been designated phosphorus recognition week.

“Our future food and water security will increasingly depend on our ability to better manage phosphorus. Finding solutions to the phosphorus paradox is of monumental significance for humankind,” she said.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

Don Flaten is equally blunt.

“The two essentials for survival are food and water. We cannot grow food without phosphorus. And we need clean potable water that’s not contaminated by phosphorus.”

The University of Manitoba soil scientist explains that there’s a limited volume of phosphorus on the planet. When it’s gone, it’s gone. That’s why we need to keep it on the land to grow food. Once it’s in the water, we’ve lost it.

Flaten responds to the notion that prairie farmers apply too much phosphorus.

“It’s just the opposite. I’d say prairie farmers are barely keeping up with their phosphorus removal. We’re just barely matching the phosphorus we remove in crop harvest. Our P application rates are rarely excessive.

“In some situations we have too much phosphorus going on with manure, but that can be avoided by spacing out the applications and hauling the manure further from the source.

“Part of the challenge in determining the best rate of P is that only 15 to 20 percent of the phosphorus you apply is used by the crop in the year of application. The crop relies on that reserve of P from previous years application. So, immediate uptake is very low. It gets tied up in the soil quite strongly. But in our western Canadian studies, the long-term uptake percentage is quite high.”

Flaten says there have been a number of microbial inoculants marketed to help the crop roots access soil-bound P. He says some of these commercial products have worked in specific situations, but the results are generally not reliable. The downside is that accessing soil-bound phosphorus accelerates the depletion of the reserve for future crops. This is why it’s important to balance phosphorus intake with phosphorus removal.

There are areas with high levels of residual phosphorus, particularly in southern Alberta and southeastern Manitoba where there are intensive livestock operations. Once phosphorus levels reach dangerous levels, the challenge is to haul manure farther away, to land that can use it. Logic dictates that this hauling distance will increase in time, as will the cost to livestock operations.

“We have regulations in Manitoba governing the amount of phosphorus that can be applied. If the P soil test reaches a certain limit, the farmer has to cut back on the application or totally stop applying to those fields. It becomes very difficult for the farmer to find an economical way to manage manure.

“Because of the high transportation costs in moving manure long distances, we encourage a long-term strategy in locating new livestock operations so there’s a sufficient land base available for manure application. The idea is to recycle the phosphorus back into the feed and food production system.”

Flaten says Manitoba has the most rigorous regulations regarding agricultural phosphorus. However, when it comes to phosphorus running directly into surface water, Manitoba’s regulations only apply to municipal waste-water treatment plants. The regulations do not apply to livestock operations.

“Even a small amount of phosphorus in the water can support the growth of blue-green algae. This is the type of algae that make the water toxic to people and animals. Some of them cause severe liver and nerve disorders in people. The entire city of Toledo, Ohio, lost its domestic water supply because of this blue-green algae.”

In August 2014, toxins from a Lake Erie algal bloom got into the drinking water system. More than half a million Toledo residents were ordered not to drink or even touch their water. The order lasted for nearly three days. Later that month, residents of Pelee Island, Ont., faced a similar crisis lasting nearly two weeks.

“Nearly all agricultural phosphorus fertilizer being applied globally is mined from phosphate rock. Those reserves are being depleted. There’s no more phosphate rock and there’s no replacement for phosphorus. If we don’t move toward recycling phosphorus, we’re going to have a very difficult time having a sustainable food production system here on Earth.

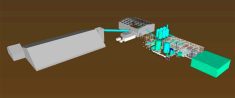

“One of the topics we’re covering for Phosphorus Week is the promotion of new ways to recycle phosphorus. For example, we have communities in Western Canada that are trapping phosphorus from waste water in their sewage treatment plants.

“This is happening in Saskatoon, Edmonton and Portage la Prairie. They convert it to commercial fertilizer, which they sell. It’s an excellent example of what can be done to build a sustainable food production system and avert a future phosphorus crisis.”