Better burn off | High quality water provides a strong foundation for spring weed control

Farmers need to pay attention to their water when spraying glyphosate, says Chelsea Norheim of Rack Petroleum in Biggar, Sask.

“With all spray solutions, 99 percent of what you spray out is water,” the agrologist said.

“It only makes sense that water should be the first thing you should be looking at in terms of quality. You are using chemicals and chemical reactions vary depending on what’s being mixed.”

Norheim said most of the groundwater in rural Western Canada is hard, containing calcium, magnesium and iron molecules. Calcium and magnesium each have two positive charges and iron has three. Glyphosate is a negatively charged molecule.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

They attract each other when mixed in the same solution. As a result, iron will tie up three molecules of glyphosate, while calcium and magnesium can each tie up two.

Varying levels of these molecules create characteristics that inactivate glyphosate, and the chemical is unable to bind to the correct pathway in the plant.

Norheim said this can make spraying more expensive and possibly a waste of time.

“Essentially, the producer is wasting money and putting chemical into the field that isn’t going anywhere or doing its job.”

She said using a water conditioner can help. The product binds up the magnesium, calcium and iron ions so that glyphosate doesn’t get tied up in the water. It can also help transfer the product into the plant faster.

Although Mike Cowbrough doesn’t dispute the science behind water conditioners, he said questions remain about how hard water affects herbicide performance.

Cowbrough, a field crop weed management specialist with the Ontario Agriculture ministry, said farmers would use water conditioners if they felt they had problems in their pesticide efficacy, but he doesn’t see that happening often.

“Since glyphosate has become basically quite a bit cheaper than what it was 20 years ago, people are using higher rates. When you use field rates that are much higher than what are in the studies, you generally don’t see a response,” he said.

“The antagonism which occurs and has been documented is basically overcome by rate. I think that’s the issue.”

Cowbrough said studies have found no problems when producers follow labelled rates and spray at good weed stages and water’s not “crazy hard.”

He said manufacturers would make recommendations on the product labels that state water hardness dramatically reduces efficacy if that was the case, but they don’t.

“Right now, in a Canadian context, I defy you to find a statement on a label that addresses hard water on glyphosate products,” he said.

Cowbrough also said current glyphosate has more concentrated formulations of active ingredients than older concentrations.

Norheim said the typical response for farmers who realize their weeds are not dying is to spray more glyphosate. Loading up the hard water ions with glyphosate allows the rest of the chemical to go to work.

Most producers would have previously been satisfied using half a litre of glyphosate per acre, but she says growers are boosting rates to maintain effectiveness.

“I don’t think it’s necessarily due to the weeds developing resistance. It’s due to the fact that you learn a product is missing things because it was being inactivated. So they start adding more and more and now we’re up to where most guys will put a litre, litre and a half in a pre-burn down.”

It’s an antiquated attitude that needs to change, said William Brown, president of AdjuventsPlus, which has developed a water conditioner.

“We’ve been told we just add more glyphosate,” he said.

“The mindset is such that more glyphosate is better.”

Brown said the trick is to avoid inactivating the glyphosate.

“The fact is you can get inactivation, or your use rate is lower because of that inactivation. The secret is to keep more of what you paid for active without loss.”

Clark Brenzil, the Saskatchewan agriculture ministry’s weed control specialist, said another solution is to cut water volumes when applying glyphosate.

“Basically, what you’re doing is you’re upping the concentration of the glyphosate in the water carrier that you’re using. By doing that, you’re making it so there’s fewer absolute ions in there to antagonize the glyphosate,” he said.

“Typically, there’s a lot of efficiencies to be found by reducing water volumes. I would say most producers have figured that one out.”

Helmut Spieser, an engineer with the Ontario government, said not all water is equal and not all water conditioners are created equal.

“You can get yourself into a bit of trouble by using them (water conditioners) when you shouldn’t,” he said.

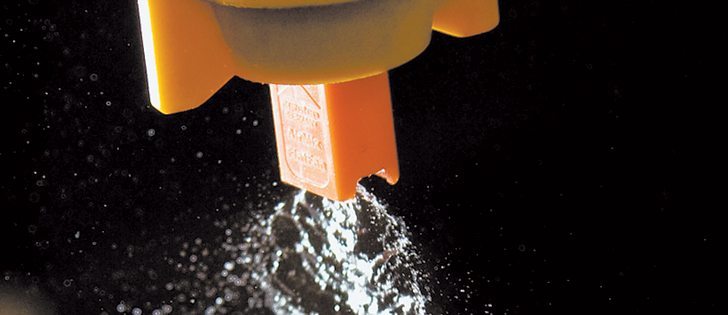

“Whether it’s an atomization problem, or the way the material deposits on the leaf, or how it acts once it gets into the leaf, you’re putting it in to do one job, but it has impact for every process that occurs beyond the (sprayer’s) tip.”

Norheim said not all weeds are created equal. Not all of them have the same chemical makeup, and some are tougher to control.

“This is why some guys increase the amount of glyphosate. The weeds have the same ions in the leaf surface that are tying up the glyphosate in the water.”

Dandelion is an example of a weed that naturally contains a lot of iron.

“So glyphosate hits the surface of the dandelion, is tied up in the iron and the glyphosate doesn’t go into the dandelion.

“That’s why it’s tough to kill,” Norheim said.

A conditioner will help tie up the iron in the water so that the plant’s iron can be targeted and glyphosate can go in and do its job.

Brown said western Canadian producers are using fairly marginal rates of glyphosate because of bad water quality, which creates a greater chance of inducing resistance.

“When you’re right at the teeter point of kill, you allow a lot more weeds to live.”

Rack Petroleum markets a water-conditioning product called Hitman. Norheim estimates that 10 percent of customers’ glyphosate acres receive the water conditioning treatment.

Norheim said using glyphosate by itself costs about $4 an acre. In comparison, a conditioning product such as Hitman will cost about 65 cents per acre and allow producers to use as little as $2 per acre of glyphosate.

“So for $2.65, you should be looking at the same results as you would for $4,” she said.

Agrologists maintain that a quality weed control strategy often begins with water rates that lean to the higher side of the recommended range. This requires water containing low amounts of minerals and soil that might interfere with chemistry.