Faster, smarter, sharper with more options describes the latest satellite technology information and services being delivered to growers.

Hundreds of the toaster-sized units orbit the Earth taking thousands of snapshots of all corners of the globe every day.

The rapid evolution in satellite technology has made high-resolution aerial field photos readily available to all farmers.

As remote sensing satellites improve, more farmers are subscribing to a list of services that companies provide.

Given the size of today’s farms, a producer rarely has time to scout thousands of acres throughout the growing season.

Read Also

Farmers asked to keep an eye out for space junk

Farmers and landowners east of Saskatoon are asked to watch for possible debris in their fields after the re-entry of a satellite in late September.

Precision agriculture has emerged through the union of satellites and precision machinery in the past two decades.

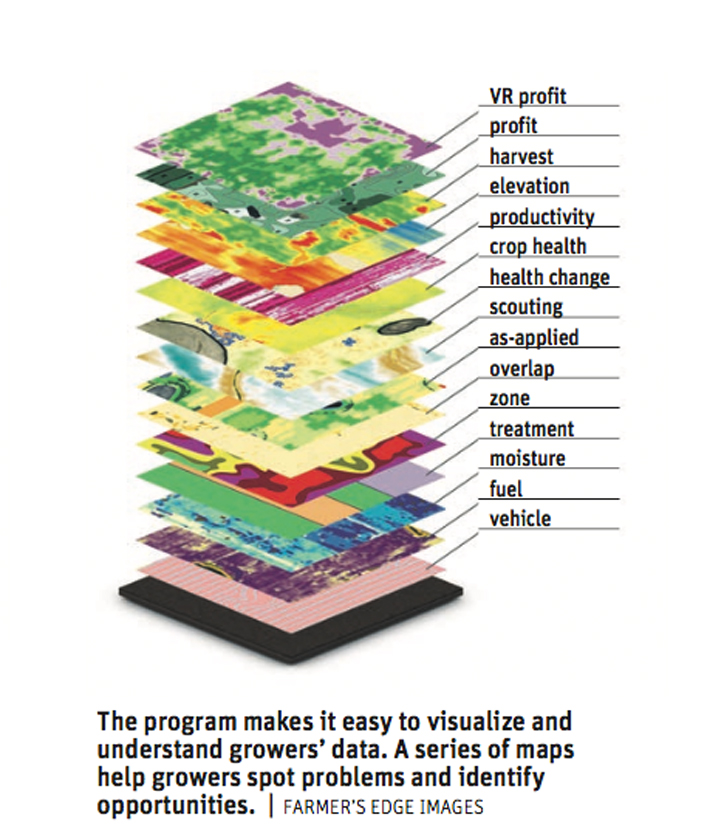

Multispectral satellites images can produce data that depicts plant health and field productivity in small zones.

As a result, farmers can better tailor their field management to meet the specific needs of crops, which results in more water efficiency, less fertilizer waste and higher yields.

What once took seven to 30 days to receive accurate and useful crop information from satellites is now measured in hours.

Image resolution is the other major barrier that has improved, which has gone from 10 to 15 metres above the crop to about three metres today.

“We’ve been delivering satellite imagery to growers for years, but we struggled like everybody with the image. The imagery was a poor resolution and less frequent and that was always the wedge when it comes to satellite imagery as a tool for farmers,” said Damon Johnson of Farmer’s Edge, one of a growing number of satellite imagery providers.

Planet Labs, which deployed their Dove constellation system of nanosatellites last year, has solved that challenge of infrequency and inconsistency of imagery.

Johnson said overcoming these two obstacles is now giving producers a proactive, actionable type of incentive.

However, rapid advancements in the technology created its own set of issues service providers needed to overcome.

“We almost went from having not frequent enough, not resolute enough imagery to literally there was an image coming to the farmer every single day,” said Johnson.

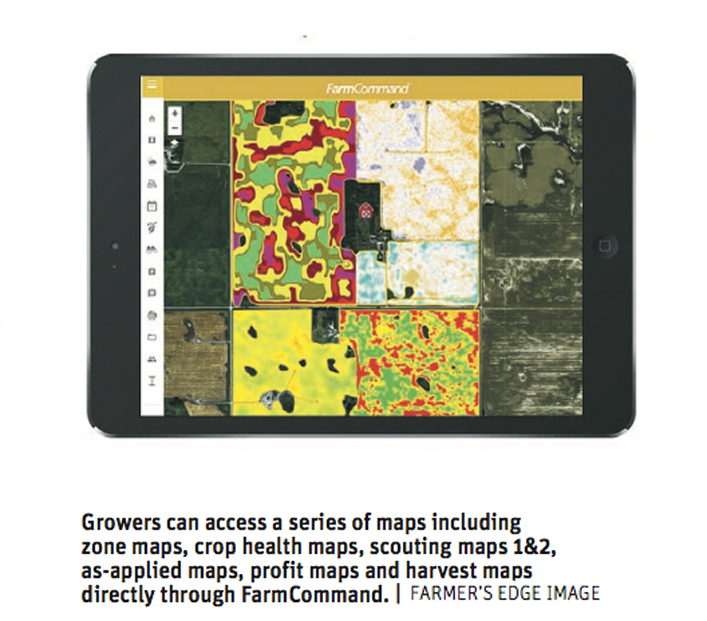

“What it did was create this massive volume coming at the farmer that was almost unmanageable. The farmer would have to sit at his computer in our farm command system and go through on a field-by-field basis and analyze the images. We were getting feedback from our growers that the build out for this digital agronomy solution needed to be simple and fast and trustworthy.”

The last two years have seen major advancements for remote sensing using normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) imagery for agricultural purposes.

The satellite’s camera is taking a near infrared image of the vegetation. The image bounces back up to the satellite where it is captured in a raw form. Companies like Farmer’s Edge then have the ability to receive and process that image and deliver the custom information directly to the individual grower.

“At its basics, what the satellite imagery is doing is it’s essentially looking for green plants and when it sends a beam down, say early in the season when there’s no vegetation cover across the field, the images are coming back and look red and orange. As the crop develops, it’s pinpointing, it’s looking for the reflection off of a green plant and sending it back up to the satellite. So across the quarter section, if there’s environmental factors such as dried-out hilltops or drowned-out low spots, areas in the field that have been affected by an insect or a disease and it’s showing a different colour of green, the satellite is picking that up. That’s essentially what’s being reported back to the grower,” he said.

Lyle Kinnaird of Virden, Man., has seen big improvements in the satellite technology during the past eight years on his 4,000-acre grain farm.

“There’s definitely a lot more usable information now than there was, that’s for sure. The imagery has evolved over the last year or two, probably the most,” he said.

The ability to see the relative health of individual crops over a season has been a real game changer for him.

“The advantages is being able to find problems without walking every square foot of the field. Certainly it streamlines a person’s day, that’s for sure,” he said. “Things have evolved now that if their (Farmer’s Edge) analytics are detecting a significant change in a field, they’ll send you an email and say you should look at this closer. Then you can look at it and maybe catch some stuff before it gets too far gone.”

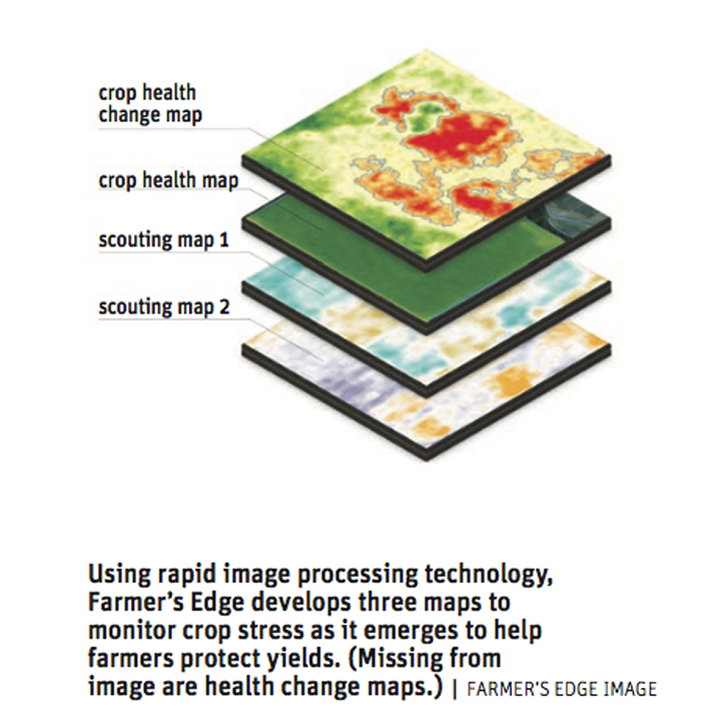

Farmer’s Edge recently launched the industry’s first automatic crop health change detection tool, which highlights the return on investment of satellite imagery.

Health Change Maps analyzes satellite images daily, pinpointing where negative changes are occurring due to possible causes, such as: pests, diseases, nutrient deficiencies, inclement weather, missed applications, equipment malfunctions, and drainage issues.

“These notifications are being sent directly to the grower on a field basis and then within each field identifying the area and how many acres are actually being affected that are deemed to be affecting crop yield,” said Johnson.

Using this new app, Kinnaird determined that fertilizer had not been properly applied over several acres in one of his wheat fields.

“I was able to see that we had that field floated with fertilizer by a custom person and I was able to see that person was going at excessive speed for that portion of the field more so than he was anywhere else. We didn’t get the fertilizer we asked for that portion,” he said.

The ability to closely monitor crop damage is a key feature for him.

“You can see if the crop health has changed because of a weather event. If there’s a change, you’ll notice it in that imagery. You can see where perhaps water has laid there or whatever,” he said.

Johnson said satellite remote sensing is an essential tool for growth stage modelling and predictive analytics on each crop — like identifying key spring application periods for herbicide and fungicide treatments, as well as staging out the maturity using desiccation for harvest.

“Satellite imagery is not just about the pretty picture, it’s the analytics that comes into our machine learning and our artificial intelligence that affects other products that we’ve just released as well,” he said.

Added Kinnaird, “It’s new, so everything in this type of stuff is evolving and I can see the benefits even though I can’t put a dollar figure on it right now other than the amount of time and expense it saves us driving from field to field to look at things in detail.”

“I think it’s a positive work in progress. As the person becomes more familiar with what it offers there’ll be more and more advantages all the time.”