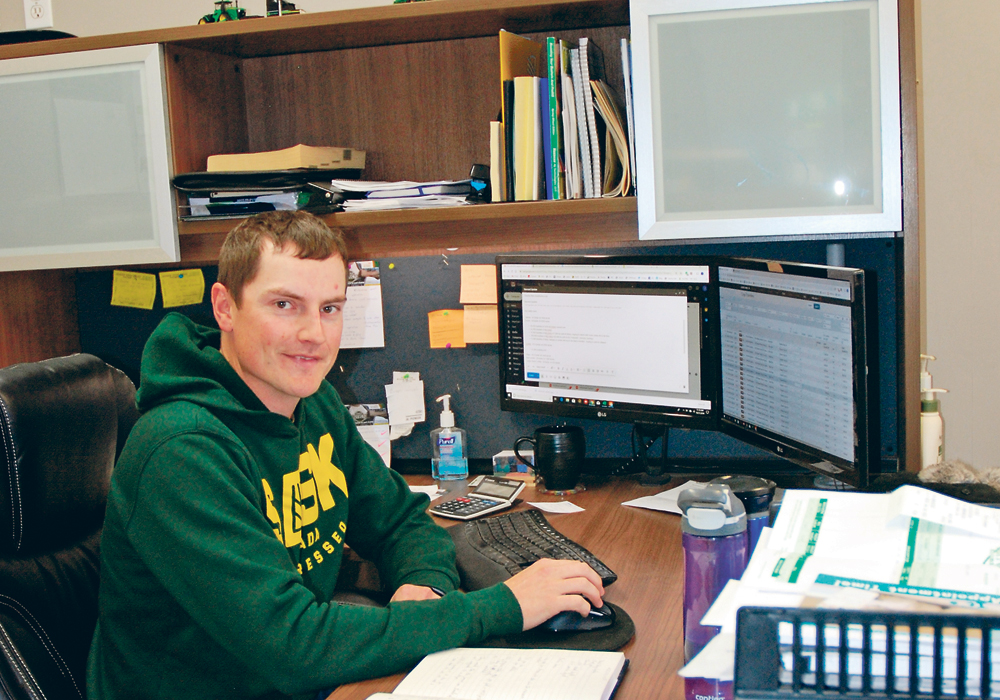

Jarrod Goldin is president of what he believes is the world’s largest livestock ranch, but there should be an asterisk attached to that claim.

“As far as livestock head count is concerned, I think we may be the biggest farm in the world because we have 110 million head of crickets,” he said.

Goldin formed Entomo Farms with his two brothers, Darren and Ryan, in 2014. They grow crickets, mealworms and other worms that are dehydrated and ground into powder that is sold to food companies to make human and pet food.

Read Also

Saskatchewan firm aims to fix soil with compost pellets

In his business, Humaterra, Leon Pratchler is helping farmers maximize yields in the weakest areas of their fields through the use of a compost pellet.

The initial product made with the insect powder was energy bars that are sold in New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

The business has expanded and the powder is now being used to make crackers, chips, pasta noodles and pasta sauce as well as dog and cat food.

They also sell whole roasted insects that people use as a salad topping or as a crunchy ingredient in tacos and wraps.

The Norwood, Ont., company has rapidly become the largest human grade insect farm in North America. Goldin estimates 80 percent of their sales are cricket products, 10 percent mealworm and 10 percent other worms.

No special legislation was required to sell insects as human food.

“There is already an allowance for insects to be in our food. It already exists. We’re just selling it separate from the food,” he said.

But companies like Entomo are pushing for specific legislation in Canada, the United States and the European Union that says insects can be used as food or feed. It will give customers and farmers peace of mind because it is a bit of a grey area in the law as it stands.

The impetus for creating the business was a 2013 white paper put out by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations titled Edible Insects: Future Prospects for Food and Feed Security?

“The paper basically contemplated that without insects entering the food and feed chain, we’re going to destroy the planet and millions of people will starve to death,” said Goldin.

He was working as a chiropractor at the time and his brothers were running Reptile Feeders, raising insects to feed to reptiles and for fish bait.

“I called my brothers up and I said, ‘maybe this is our chance to all work together,’ ” said Goldin.

According to the FAO paper, insects provide high quality protein comparable with meat and fish and are high in fatty acids and rich in fibre and micronutrients.

There are no known cases of transmission of diseases or parasitoids to humans from eating insects.

The paper also said they offer a variety of environmental benefits.

The main benefit is they require less feed because they are cold-blooded. On average insects convert two kilograms of feed into one kilogram of mass while cattle require eight kilograms of feed for one kilogram of weight gain.

Insects produce little methane compared to conventional livestock. For instance, pigs produce 10 to 100 times more greenhouse gases per kilogram of weight than mealworms.

And insects use far less water than conventional livestock. It takes 100 gallons of water to produce one pound of meat protein versus less than one gallon for the equivalent amount of insect protein.

There are concerns about insects causing shellfish allergies because they are both invertebrates. Goldin said they have tested their powder and the shellfish allergy protein is not there but they still put a warning on their packages.

Many people are already regularly consuming insects. The FAO estimates insects supplement the diets of about two billion people worldwide.

Business is booming at Entomo. The company had 5,000 sq. feet of barn space when it started in January of 2014. That has grown to 60,000 sq. feet. The business employs 17 people.

Sales would really take off if governments around the world allowed insects to be fed to livestock. The feed market has “massive” potential compared to the food market.

However, many countries have bovine spongiform encephalopathy inspired legislation forbidding the feeding of animals to livestock. Insects are animals, so the industry is entangled in that legislation.

The FAO would like to see a subtle change in the legislation so that it prevents the feeding of mammals to livestock.

In July 2016, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency became the first regulatory body in North America to approve farmed maggots as feed for broiler chickens.

Enterra Feed Corp., an insect farm in Langley, B.C., had been lobbying for that approval for years.

FeedNavigator.com recently hosted a web forum on novel protein sources for the feed industry.

The consensus of the four experts on the panel seemed to be there is no urgent need for insect-based protein but in five to 10 years the ingredient could start making inroads in the feed sector.

Leon Marchal, director of nutrition and innovation with ForFarmers N.V., an international feed company based in the Netherlands, says there has been a trend in recent years toward using a much wider variety of protein sources such as synthetic amino acids, rapeseed meal and pulse crops.

He believes the list will eventually expand to include insect protein.

“There is really a need to push this forward and I think it will be imminent in the next decade,” he said.

Gorjan Nikolik, senior aquaculture industry analyst with Rabobank International, says there is no urgent need to replace fishmeal.

“The properties it provides are worth the cost,” he said.

But there is an acute need to find a fish oil replacement because a shortage of the ingredient could start impeding the growth of the farmed salmon industry within a few years.

Arnold van Huis, tropical entomologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, said soy is a poor replacement for fishmeal. It has too much fibre, poor composition of amino acids and too many anti-nutritional components.

Black soldier flies, on the other hand, are strong candidates for replacing fishmeal in the diets of farmed fish. If the food is de-fatted, it has the same protein content of fishmeal.

If legislation is changed to allow insect meal in animal diets, there are companies that could be producing 30 tonnes a week.

“There are absolutely huge possibilities,” said van Huis.

Marchal has experimented with using whole larvae in chicken diets but at the moment the ingredient is too expensive so there needs to be an advantage beyond nutritional value and he thinks they may have found it.

“We saw much more lively behaviour of the chicks. They really liked going after and pecking on the live larvae,” he said.

“Feeding live larvae could be a benefit because it stimulates the natural behaviour of the broiler chicks.”

Van Huis has witnessed the same thing feeding black soldier fly larvae to pigs.

“They have to forage for those larvae and that also seems to increase welfare and reduce tail biting,” he said.

Nikolik said the industry needs to scale up production to get prices down to a level where feed manufacturers will incorporate insect meal in feed rations.

The problem is that insect farms do not have assets that are attractive to bankers as collateral.

“It becomes very difficult to finance and without finance you can’t reach the scale and without the scale you can’t get to the low cost,” he said.

Marchal said consumer acceptance is also a big obstacle, as is the mounting pressure from animal welfare groups in the European Union.

Algae offers another alternative form of protein that does not face those last two obstacles.

“The problem so far is the high-cost price,” said Gert Hemke, animal nutritionist with Hemke Nutri Consult.

It sells for US$7.42 to $10.60 per kilogram. There is a market for using algae as an anti-inflammatory ingredient in pet food and for horse diets but not in poultry, pigs or cattle yet.

It has a worse amino acid profile than fishmeal but many beneficial bioactive traits such as its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant traits. It also contains high levels of omega-3 fatty acid, said Hemke.

Marchal said the earliest opportunities are for macro-algae products like duckweed that float on the surface of water and are easy to grow and harvest.

It is best suited to dairy, gestating sow and laying hen diets due to its combination of high fibre and high protein.

Nikolik said another protein alternative that shows promise is methane-gas-based protein. Naturally occurring bacteria feed on the methane and multiply rapidly, creating a meal with 70 percent protein content.

“It could be a pretty close substitute for fishmeal,” he said.

There are environmental concerns about using methane gas to create feed but those disappear when manure is the source of methane.

Cargill has invested millions of dollars in the technology.

“This is the most likely candidate to reach scale within five years,” said Nikolik.

Marchal said 1,700 cubic metres of methane are required to make one tonne of protein, so it works only when methane prices are low.

Hemke said methane is better used for other purposes. Algae bind to carbon dioxide, so it is a far more environmentally friendly way to produce protein.