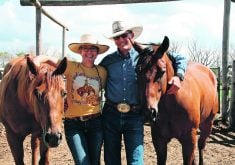

On the Farm: Organic farming comes naturally to this producer, who works with parents Nettie Wiebe and Jim Robbins

LAURA, Sask. — Will Robbins’ head told him he would never farm.

His heart knew better.

Like the slow drip of a coffee machine, the idea of pursuing an agricultural livelihood percolated for years.

“I didn’t think of it as a career or a project that was mine really at the time when I was a kid and I went to university thinking I would do other things,” he said.

It wasn’t until his parents, Jim Robbins and Nettie Wiebe, discussed retirement that he perked up to the notion that farming was his future.

Robbins and his sisters, Martha, Katie and Margaret, discussed whether any of them planned to run the farm.

He said his parents emphasized there was no obligation, but if any of their children wanted to take over, they were glad to accommodate it.

Four years ago, Robbins took the plunge. He hasn’t looked back.

The Robbins’ 2,500 acre organic farm near Laura, Sask., was homesteaded by Jim’s grandparents in 1908.

About a kilometre from the original homestead, their comfortable two-storey home was designed by Nettie and built in 1980 featuring energy efficiency and repurposed materials.

The bright yellow clapboard, surrounded by tall evergreens, is a reflection of her ideologies.

“I’m deeply committed to conservation. I think we can’t continue to use new materials and throw them away. I think our biosystems are beginning to instruct us. That kind of waste, that kind of flagrant use of resources is unsustainable and unnecessary,” said Wiebe.

She is well-known as a university professor and president of the National Farmers Union from 1988-94. She has also run as the New Democratic Party candidate in several federal elections.

Robbins and Wiebe were the first farmers in the area to transition from conventional to organic agriculture back in the 1990s.

Read Also

Nutritious pork packed with vitamins, essential minerals

Recipes for pork

Their operation includes more than 100 head of cattle, which they finish for organic meat. About 1,500 acres are in hay and pasture while the other 1000 acres is cultivated.

The cattle are integral to land use.

“For us it’s an important part of the organics. We have a higher weed burden in our fields and so we rough clean everything before we bin it,” said Wiebe.

“We sort out the weed seed, the splits, etc. Jim grinds them up and that’s our feed for the yearlings that we finish. In fall, we clean out the corrals and we spread the manure. So that’s part of our fertilizer and the important part of the cattle is that we have land that we rotate into hay, which rehabilitates the land (and) suppresses the weeds. And then we have quite a bit of land which isn’t suitable for grain production, and so it’s a suitable pastureland.”

Organic farming is also a good match for Robbins’ farming ideology. He has a master’s degree in philosophy, has travelled and lived in several countries and worked in a variety of jobs.

“One of the real appeals to me about farming is that there’s no end to learning how to do it,” said Robbins.

“Because agriculture is so dynamic and you’re dealing with complicated and very intricate biological systems, there’s sort of an endless amount to learn about your own land base and how it works and what works and doesn’t on it…. There’s sort of this endless learning curve,” he said.

Since returning to the farm, he’s been leaning on his parents and neighbours for their expertise.

He lives in Saskatoon with partner Mairin Loewen and their two-year-old son, Asa, and commutes the 40 minutes to the farm.

Robbins said he plans to grow the family operation with its current land base. Remaining organic is key and appeals to his financially conservative nature.

“It makes me nervous to owe huge amounts of money to banks and chemical companies. I’d rather not, all things being equal. It (organic) allows us to maintain a family farm size without having to be expansionist.

“We’re still dependent in many ways, on seed growers and diesel fuel and those kinds of things, but it allows us to be a little bit more independent.”

Future plans include upgrading the seed-cleaning equipment and increasing direct marketing aspects.

His organic wheat and lentils are in demand in several restaurants and bakeries in Saskatoon and Vancouver and he sees growing interest among consumers in buying local, buying organic, and knowing food sources.

“There are those parts of the farm that … are much easier to do in organics. I would say I have an ideological commitment also to the project and organic agriculture.”

Besides hard red spring wheat, this year’s crops include oats, French green lentils and yellow field peas.

Before Robbins started farming full-time, his parents had scaled back their rotations.

“We were transitioning but then when William came we’ve gotten much more complex, with four crops and maybe six and eight and 10,” Wiebe said.

“I’m doing far fewer tractor hours then I did those last years because William’s doing a lot of the work, but in terms of the complexity of the farm and what we’re doing now, it’s become more interesting again and more work.”

Added Jim: “We’re thrilled that Will is back farming and the farm will stay in the family and we’ll stay organic.”

Wiebe shares those thoughts.

“It’s such an unmitigated joy to know that the farm is going to continue as a family farm…. That satisfaction of knowing that the yard, the house, the land that you’ve loved and taken care of will be loved and taken care of. I think people shouldn’t underestimate how much that’s worth.”