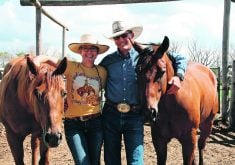

On the Farm: Rick and Marilyn Neville are major advocates for using sheep to manage pasture, but it must have a goal

LUNDBRECK, Alta. — After spending many summers grazing sheep in many pastures, the shepherds have come home to their own flock.

Marilyn and Rick Neville have a quarter section of land and 70 Suffolk-cross ewes along Todd Creek, in the shadow of the Livingstone Range.

They’ve lived here since 1979 when they decided to buy land and seek pursuits beyond guiding and ski resort development in Banff.

“It was getting way too crowded in Banff,” says Rick, “and you couldn’t afford to have your own place.”

Read Also

Accurate accounting, inventory records are important

Maintaining detailed accounting and inventory records is not just a best practice; it’s a critical component of financial health, operational efficiency and compliance with programs like AgriStability.

Marilyn, who grew up west of Claresholm, Alta., has always loved the area, so buying this property was an easy transition. Rick was raised in upstate New York and because he had some experience with sheep through his uncle’s flock, they opted to raise a sheep flock on their own native and tame grass.

At one time they had more than 300 ewes, which they grazed through various arrangements with ranchers, who were seeking solutions to weed problems or brush encroachment.

Back then their children, Liam and Heather, were young and could spend summers with their parents, herding sheep during the day and making camp at night.

“Those were the best years of our lives,” Marilyn recalls. “We had our kids there and we spent the whole summer on horseback.”

Rick and Marilyn are major advocates for using sheep to manage pasture but they say the key is to define a landscape goal before embarking on projects. It’s also vital to understand what sheep can do to improve thorny problems, such as leafy spurge control, while sparing native grasses that are vital to cattle grazing.

“Lots of problems can be solved through good grazing rather than spraying. I think we’ve provided that over the years,” Rick says.

They curtailed their own flock after the BSE crisis of 2003, when international borders closed to ovine as well as bovines. By then, they had established a freezer trade, selling lamb direct to customers, which helped carry them through.

However, it also required them to seek additional jobs. Marilyn milked cows at a dairy and Rick worked for the forest service, building campgrounds and cross-country ski trails.

They still have their freezer trade today.

“We have a lot of customers,” says Marilyn. “The freezer trade, it takes a lot of work, but we’ve got a system down.”

They also sell animals at auction, depending on price and the availability of grazing.

The Nevilles lamb once a year, generally toward the end of March so the lambs can go out on pasture with the ewes as soon as possible.

“We don’t raise animals in confinement,” says Rick. “It’s a distinctive lamb that we raise here.”

Though lamb prices have improved in recent years, most sheep operations including theirs operate on very slim margins.

“There’s a lot of husbandry involved with sheep and people don’t realize it,” says Marilyn.

Adds Rick: “There’s a lot of people that think it’s cool to have sheep,” but it is not an easy task.

He says the industry needs another packing plant, for one thing, and other marketing options besides a new venture announced last year to form North American Lamb Company.

The Nevilles focus on lamb rather than wool as their revenue stream. The nearby Livingstone Hutterite Colony looks after the shearing. Wool breeds aren’t the same as meat breeds and it takes longer for the former to finish.

They’ve found the Suffolk-cross animals do well on range.

“We’ve always bought locally or from people who also have range operations,” says Marilyn. “There’s no use having an animal here that can’t survive.”

Years spent observing sheep has taught them the animals like variety and dislike hard grass, preferring leafy weeds and shrubs. That’s why sheep are so good at pasture management.

Grass management, biodiversity and landscape restoration are subjects close to Marilyn’s heart. She operates a consulting business, Gramineae Services Ltd., that advises on restoration of native grassland following projects such as pipeline installation and other energy industry site disturbance.

“People just don’t realize the effort that goes into restoration,” says Marilyn. “We have the best standards in the world in Alberta and Canada. The effort and methods (of grassland restoration) are not well understood.”

As for the future of the farm, dubbed Glenfiddich Ranch, Rick and Marilyn say their children have established their own careers and lives but perhaps one of their five grandchildren will fall in love with the place just as they did.

Their son, Liam, ranches in southern Saskatchewan and works as a range rider, where his experience with grazing and grasslands comes in handy. Their daughter, Heather, lives in Lethbridge with her husband, a cabinetmaker.