A federal mandate to reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions by levying a tax on fossil fuels, emissions and fertilizers has not been well received. Are farmers justified in their fears that the new tax will place undue economic costs on the ag sector?

Canada’s plan to implement a tax on greenhouse gas emissions has caused a fair bit of hand wringing among prairie farmers.

However, the financial impact of a carbon tax on the western Canadian agriculture sector could be far smaller than expected, according to agricultural economists at the University of Saskatchewan.

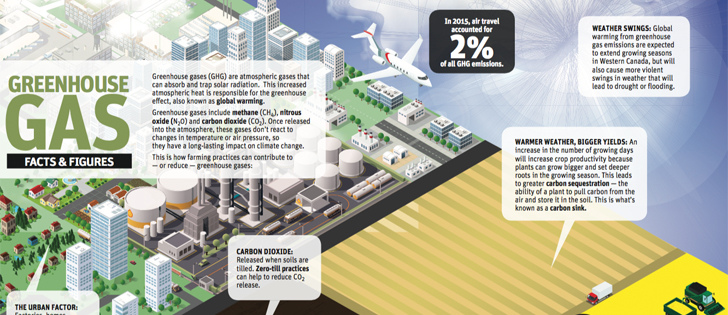

That’s because biological emissions, which are those associated with growing crops or raising livestock, will not be taxed under Ottawa’s proposed carbon tax plan.

In addition, Ottawa has indicated that the consumption of gasoline and diesel fuel by agricultural producers will be exempt from a proposed fossil fuel levy.

Read Also

Using artificial intelligence in agriculture starts with the right data

Good data is critical as the agriculture sector increasingly adopts new AI technology to drive efficiency, sustainability and trust across all levels of the value chain.

For farmers, that means the greatest financial impact will likely be felt indirectly and be reflected in higher costs for some goods and services used by farmers, such as agricultural inputs, nitrogen fertilizers, farm chemicals, transportation services and freight rates for moving grain by rail.

“If you look at where most emissions come from in (the agriculture sector), a lot of them are biological emissions from things like fertilizer applications … methane emissions from cattle, et cetera, et cetera,” said Peter Slade, an agricultural economist at the U of S.

Links to other stories in this Special Report:

- Alberta’s carbon tax plan may offer insight for others

- Carbon tax: A bitter pill for farmers

- Scientists find surprise in soil’s freeze-thaw cycle: nitrous oxide emissions

- Alfalfa, grasses top choices to aid in carbon sequestration

- Carbon tax Down Under went under

- Meeting EU emission standards can be a hurdle

- Can equipment makers do more to make a greener machine?

- Download a PDF of the complete Special Report here

“But all of these things are not going to be taxed under the federal plan or under any provincial plans that I’ve seen, so all of those types of things would be counted outside of the carbon tax.”

Tristan Skolrud, another ag economist at the U of S, agreed.

Although all the details of the federal carbon tax plan have yet to be unveiled, it looks like consumption of fossil fuels on the farm will be tax exempt, at least for the time being, Skolrud said.

“Realistically, they (farmers) are just going to be looking at indirect effects,” said Skolrud, an assistant professor in agricultural economics department.

“For example, they might end up paying more for certain farm inputs…. The biggest potential there is for higher nitrogen fertilizer costs because producing nitrogen fertilizer is a very carbon intensive process, and if nitrogen fertilizer manufacturers are taxed, there’s a chance that some of those costs will get passed on to the final purchasers.”

However, Skolrud said domestic producers of nitrogen fertilizer will be forced to keep fertilizer prices at a competitive level, relative to nitrogen fertilizer products imported from the United States or elsewhere.

Slade and Skolrud said there are many unanswered questions surrounding the federal carbon tax program.

It remains to be seen how things will roll out, but prairie farmers should not assume that the implementation of a carbon tax will be the difference between financial success and financial failure on the farm.

In general, economists agree that it makes more sense to tax pollution, which has a negative impact on society, rather than retail sales, which contribute to a healthier economy.

In theory, a carbon tax would be revenue neutral, meaning revenues that are collected could be used to offset existing taxes in other areas.

Ottawa offered some hints about what form the federal carbon tax will take in the Technical Paper on the Federal Carbon Pricing Backstop, available at bit.ly/2suM1bE.

According to the paper, all provinces in Canada will have the latitude to come up with their own carbon pricing systems.

However, the federal government’s carbon pricing “backstop” will kick in if a province doesn’t come up with its own pricing and taxation plan.

The federal backstop will price carbon dioxide or carbon dioxide equivalents at $10 per tonne in 2018 and increase to $50 per tonne by 2022.

In addition, Ottawa will also introduce:

- A tax levy on all types of liquid, solid and gaseous fuel, including gasoline, diesel fuel, natural gas, propane, fuel oil and coal and even waste tires with exemptions granted on certain types for agricultural activities.

- An output-based pricing system that will apply to all industrial facilities that emit 50 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year.

For gasoline consumers, the fuel levy will be equivalent to a tax of 2.33 cents per litre in 2018 and increasing to 11.63 cents per litre in 2022.

Some groups will be exempt from paying the fuel levy, including “registered farmers” involved in “certain farming activities.”

The Saskatchewan government opposes a carbon tax, suggesting it will discourage economic activity.

There are also lingering questions about the value of activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and sequester carbons, most notably, the adoption of zero-till or minimum till production systems.

In a recent academic paper co-authored by University of Saskatchewan economists Lana Awada, Richard Gray and Cecil Nagy, the economic value of adopting zero-till in Saskatchewan was estimated at $590 million between 1985 and 2012.

This included the value of sequestered carbon ($542 million), CO2 reductions related to reduced farm fuel consumption ($37 million) and gains from reduced nitrous oxide emissions ($11 million).

The researchers assigned a value of $5 as the social cost of emitting a tonne of carbon dioxide or carbon dioxide equivalent.

By comparison, Ottawa’s backstop plan will assign a value of $10 per tonne in 2018, increasing to $50 per tonne by 2022.

Awada said it is unclear if farmers will receive credits or compensation for adopting production systems that sequester carbon and benefit the environment.

However, she thinks their efforts should be rewarded.

“Farmers’ adoption of zero tillage has probably made the largest contribution to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in Saskatchewan, but to date farmers have not yet been compensated for that,” she said.

“Carbon credit programs to reward on-farm carbon sequestration are needed. These programs will help farmers get an idea about the GHG emissions associated with particular practices and the prospects for earning carbon credits.”

The Saskatchewan Soil Conservation Association has proposed that Saskatchewan farmers, in partnership with the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corp., develop a soil carbon registry or bank.

The bank would allow farmers to accumulate and “bank” credits or offsets in exchange for adopting carbon-reducing practices on the farm, such as no-till production.

The credits accumulated in the bank could then be used to pay other carbon related taxes or penalties that are levied by any level of government under federal or provincial carbon tax schemes.

Farmers would not be responsible for calculating their own soil carbon levels. That responsibility would rest with the organization responsible for running the credit program and would be based on farmers’ management practices.