It isn’t fun being a farmer living inside an economic theory if that theory states that crop prices will get lower over time.

But that’s the fate of farmers, according to the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis.

And aware of the hypothesis or not, most prairie farmers act in accordance with its dictates.

“Efficiency. Right size. Right size equipment. No excess labour. Do whatever you can yourself. Improve everything a little bit better,” said Radisson, Sask., farmer Corey Loessin in response to a Western Producer question on Twitter about how farmers respond to low prices.

Read Also

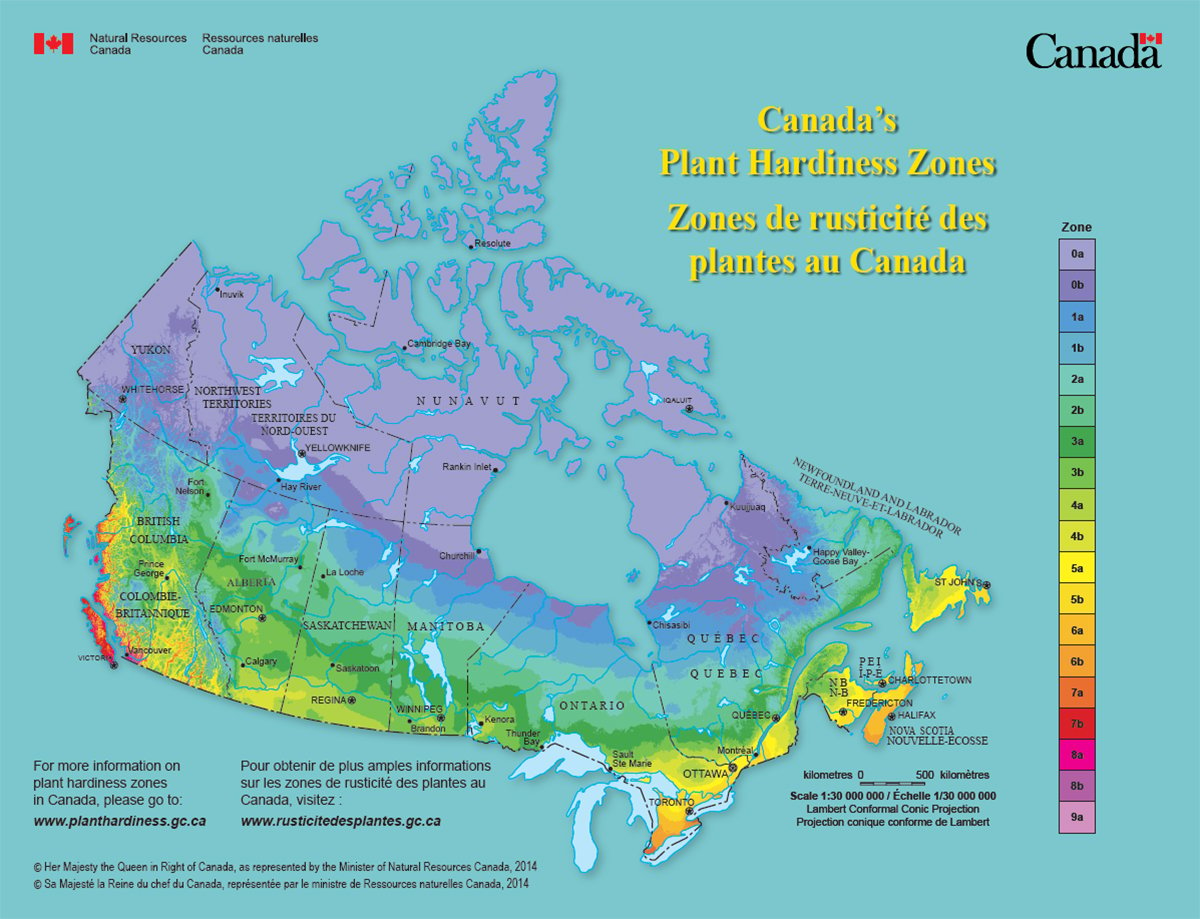

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Korey Peters, a Randolph, Man., farmer, tweeted that he deals with constant pressure on profitability by trying to boost the productivity of his land.

Related stories in this Special Report:

“Work at improving land through organic matter, drainage and crop choice. Seems more (farmers) are going specialized,” Peters said.

Crop farmers experienced an incredible boom from 2006 to 2012, with prices soaring high above low levels low levels where they had lingered since the early 1980s.

That brought some high profits and an easing of the constant pressure most had grown accustomed to facing. The surge of high prices, similar to the one from the early 1970s to early 1980s, was described as the high phase of the “commodity supercycle,” and allowed many farmers to pay down debts, expand the land holdings, replace equipment and dream of a better future.

Some hoped they had finally hit easy street after decades of tough times.

But then the boom ended in 2013 and farmers have been back in the world of thin profits and the never-ending search for ways to produce more crops for less.

This is completely in keeping with the Prebish-Singer hypothesis, theorized by two economists in the late 1940s. It argues that over the very long term, most commodity prices get lower in inflation- and currency-adjusted terms.

Commodities are volatile and during the course of a supercycle can rise 20-40 percent above the long-term trend line, and fall 20-40 percent beneath it.

This can mask the inexorable grind to long-term lower commodity prices, as can currency and inflation factors. Farms that have survived repeated booms and busts generally focus on maximizing their efficiency of production, something which provides the best protection against steady pressure on profitability, according to David Kohl, a well-known agricultural economist who operates the Kohl Centre at Virginia Tech University.

“During the supercycle you could… make money because the economics were good. Now, whether you’re big or small, you also have to sweat the small stuff,” said Kohl.

Farmers might not be familiar with the term “Prebisch-Singer hypothesis,” but those who have survived its challenges act as if they know it very well.