Louisville, Ky. – When Montana rancher Lee Arbuckle set out to develop a new method for harvesting native grass seed, he accepted the fact that patience had never been one of his virtues.

Arbuckle knew what farmer-inventors go through. He made up his mind that he would not get trapped in the typically prolonged process of building a machine in the shop the first winter, testing it the first summer, bringing it back into the shop the second winter and then cutting it apart to try again.

Read Also

VIDEO: Green Lightning and Nytro Ag win sustainability innovation award

Nytro Ag Corp and Green Lightning recieved an innovation award at Ag in Motion 2025 for the Green Lightning Nitrogen Machine, which converts atmospheric nitrogen into a plant-usable form.

“On and on and on for 10 years or more,” said Arbuckle, shaking his head.

“I just don’t have the patience for that kind of thing anymore.”

Arbuckle, who admited that some people seem to have a tendency to grow impatient with the passage of time, is emphatic about his intentions.

“I wanted to build this thing right or as nearly right as possible the first time around. You can’t do that with the old trial and error method. You have to try the kinds of new technology the major industrial companies use.

“We realized right off the bat that we couldn’t get the same engineering programs John Deere has, but there’s a lot of design software available nowadays that a person like myself can buy and use.”

As it turned out, Arbuckle was able to use design technology that even major agricultural manufacturers had not put to use.

“To the best of our knowledge, nobody had used high speed video to analyze seed movement in a combine,” said Arbuckle.

“We did that in 2002. I had an engineer from a major combine manufacturer tell me I was using high speed video before they had even thought about it.”

Although the R&D process was not as simple as setting up a DVD player, it was not impossible. His first major tool was SolidWorks design software. He also pioneered the use of high speed, high quality digital video at 1,000 to 1,200 frames per second.

As well, Arbuckle brought together a team of experts who were spread across the continent geographically, but electronically connected for their design meetings.

SolidWorks software is a user friendly version of the CAD (computer assisted design) system used by industry. It allows a person who does not have formal training as a mechanical engineer or computer programmer to design objects on the computer and then analyze them in three dimensional images.

“Not everybody can understand what they see on a two dimensional blueprint on paper,” said Arbuckle.

“But if you take the design and put it into three dimensions on a computer screen so you can rotate it around to different angles, then all of a sudden it begins to makes sense.

“You can see what you’re doing right and what you’re doing wrong and it doesn’t cost you a full summer of trial and error. You quickly grasp what’s happening and you can make your decisions to improve the machine.”

He said SolidWorks let him make modifications on-screen while maintaining strict tolerances. SolidWorks also let him digitally communicate to the machine shop where water jet cutting took the guesswork out of each component.

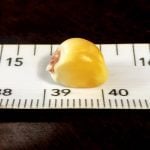

For his accelerated research and development program to proceed on schedule, Arbuckle knew he would need to study each seed as it was plucked and sucked away by the air flow.

The solution was high speed video cameras capable of capturing 1,000 to 1,200 frames per second.

“No matter how smart you think you are, there is no substitute for slowing down the action for detailed study,” he said.

“We took the action of air and seeds at 60 mph and brought it down to a slow crawl across the screen. If we wanted to freeze frame, we could do that and capture high quality still images.”

Although viewing every still image from a 1,000 frame per second camera is time prohibitive, Arbuckle said randomly selecting video clips showed them how the seeds acted in the plucker machine.

“We can see the precise moment a seed is dislodged. You can see how it’s touched by the comb and the brush and then you can follow it to see if the air flow bounces it around too much,” he said.

“You would never learn these things through trial and error. Often people try to analyze things and draw results based on what they think should happen. High speed video doesn’t let you get away with that. High speed video puts the truth right there on the screen in front of your eyes.”

One of Arbuckle’s major tools is what he called his virtual team of specialists from a range of fields. At any time, he could consult with engineers, agrologists, commercial seed growers, marketing specialists and botanists specializing in native plants.

Although the team members were located across the continent, Arbuckle said the computer link-ups with the SolidWorks software, along with conference calls, brought the team together on short notice whenever a decision was required.

Arbuckle said this was where the SolidWorks gave the team a major benefit it had not anticipated.

“We’d run up against a problem, so I’d schedule a one hour conference call meeting of the whole team. We could all see the model in front of us as we discussed the problem of the day,” he said. “It was hard to stretch those meeting to 30 minutes. With everyone working together on the phone and the computer, we could figure things out in no time. It was a truly amazing process.”

Arbuckle said there is one other advantage to bringing together a team of experts, high speed video and SolidWorks software.

“There’s no pile of prototypes out behind my shop.”