A picture is worth a thousand words — but which words? When looking at a photograph, what we ask is perhaps more important than having the answer. Questions can help us interpret and understand photographs in a thoughtful way.

Many moons ago, in the mid 1980s, I lived in Washington D.C. One evening I attended a White House news photographer’s function. I spoke with my boss, Rich Clarkson, then director of photography at National Geographic, and with Dirck Halstead, a TIME photographer. Halstead asked me if I read the Geographic.

Read Also

Rural communities can be a fishbowl for politicians, reporter

Western Producer reporter draws comparisons between urban and rural journalism and governance

In those days, it was something of a quip among photographers that few actually read the stories within the “yellow jacket — they just looked at the photographs. I admit that I studied the photographs intensely and seldom gave equal energy to the well crafted words. I hesitated with a reply and Rich answered for me. “Yes he does. He reads the photos.”

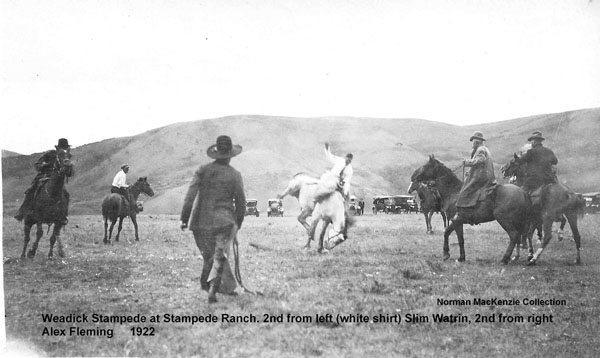

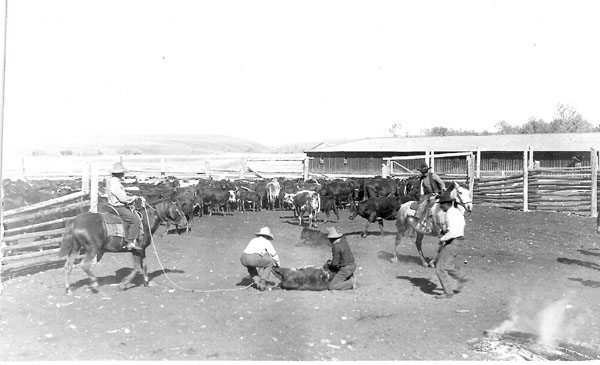

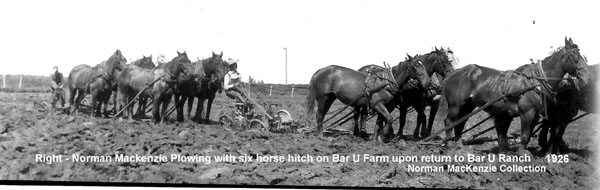

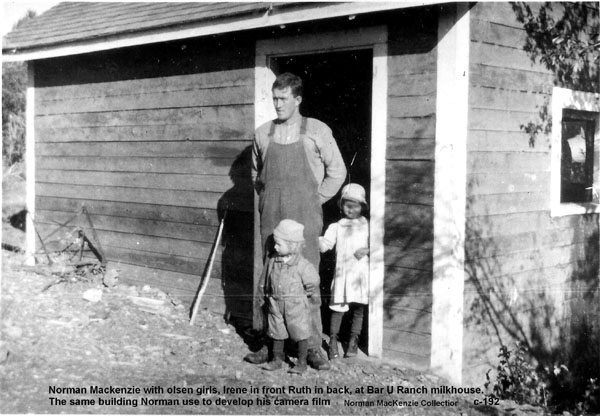

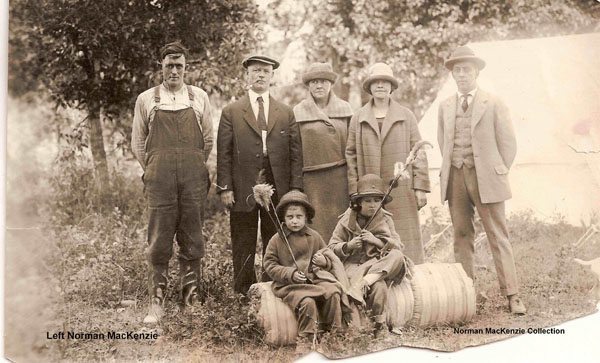

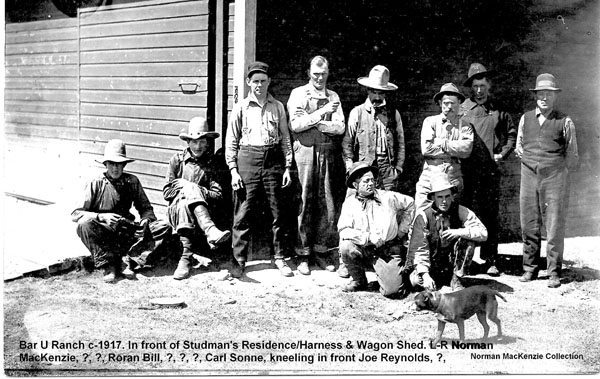

Reading photographs brings me to this week’s blog, which features some images by the late Norman MacKenzie, who died in 1977.

I never knew Norman. I don’t know his family and never been to his home. His son, Alex, sent us a branding photo that his dad had made at southern Alberta’s Bar U ranch in the early 1920s. All I know about Norman MacKenzie is in the photographs he and others made while working at the Bar U from 1918 to 1928 or ‘29.

I don’t know who, or what inspired the young ranch hand to buy a Kodak folding bellows camera from Eatons. His interest in photography led him to develop his 220 film inside the little milk house where a creek ran through. Among the cool milk tanks and butter and cream equipment, Norman would close off the one window and door to develop and wash his film in the creek water.

What we have, thanks in part to Alex’s diligence, is a time capsule of frontier life on the Canadian Prairies.

Alex says he wishes he had paid more attention when he was a boy and his father would bring out the photos and tell stories. “I don’t think people really pay that much attention until they get about 60 years of age or so. Then they start to wonder where they came from,” he says.

Each of us carries within us many unwritten and unread chapters of our own stories. Perhaps only in retrospect can we see how fate intervened in our lives.

Norman and his identical twin brother were born in 1894 at Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. His Gaelic-speaking family were strict Presbyterians who kept cattle and sheep, and in the winter fished off the coast.

When the MacKenzie brothers were of age, they applied to join the army, but Norman, who said in his application that he was just shy of six feet, was not accepted. His twin reported his height as six feet and was accepted. He later died in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) during the First World War. Soon after Norman’s rejection by the army he decided to journey to Canada.

Fate again intervened in Norman’s life. He and a buddy booked passage to Canada on a new steamer, Titanic. But their plans changed before the sailing and they travelled later in 1912 or 1913.

Soon after Norman left the Bar U, he married his sweetheart, started his own farm and began raising a family. The depression was well underway.

I’ll speak more specifically in future blogs about reading photos. If you also have a photographer in the family from our early Canadian history, please feel free to send along their photos for discussion.