Wanna know why Canadian traders, analysts and farm newspapers often seem to obsess about U.S. crops like soybeans, corn and winter wheat?

It’s all to do with the “dirty little secret” underlying most of our prairie crops’ markets.

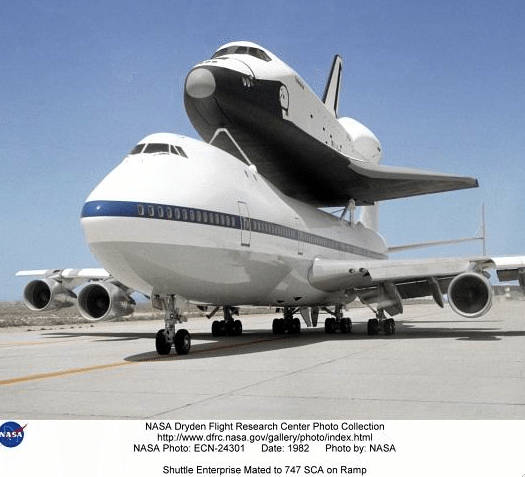

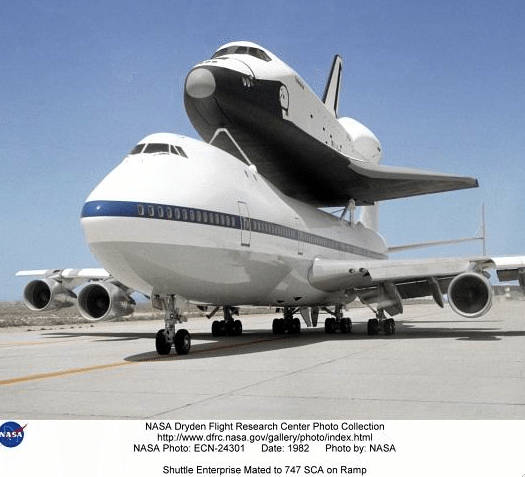

Here’s a version of the image Cargill risk management expert David Reimann uses to explain the direction canola’s going to go:

Read Also

Agriculture productivity can be increased with little or no cost

There’s a way to enhance agricultural productivity with little or no cost. It doesn’t even require a bunch of legislative changes.

The canola market’s the space shuttle. The 747 is the soybean market.

You get the idea, right? The shuttle ain’t going too far without that 747 taking it there.

Reimann brought up this idea at Grainworld a couple of weeks ago as a way of highlighting the need to understand the broader crop markets if you want to understand where canola prices are and where they might go.

“In reality, it’s the soy complex that really drives this market,” said Reimann.

Anyone who follows markets closely enough knows this to be true not only about canola’s connection to soybeans, but also to soy oil, to crude oil and to the larger commodity complex that includes metals and everything else. Crop commodities are just a small part of the world’s gigantoid commodities pile and tightly connected to it by many little connections. Obviously canola and soybeans are going to be connected because both crops can be crushed to produce a vegetable oil. They won’t be 100 percent connected because each produces a different proportion of oil, and the two oils are different, but at the edges they can be swapped out for each other.

The same goes for the connection of crops to energy commodities like crude oil. Canola oil can be made into biodiesel, so at the edges canola demand is affected by what goes on in the energy markets.

And more broadly, when money pours into or flushes out of commodities from investors looking for hard assets to own, crop prices are affected.

All these factors apply to every one of our crops, often to a dominant degree. Barley is shoved around by corn. Prairie wheat is affected by Chicago, (formerly) Kansas City and Minneapolis wheat. When commodities roar higher, crops will probably go along for the ride. When they slump, they’ll probably go down too.

Farmers, analysts and traders all obsess about the specific market dynamics of canola supplies and demand, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Those factors will definitely affect the spread between crops like canola and underlying commodity price drivers like soybeans and crude oil. But they only affect prices at the margin, not the overwhelming bulk of the price of the crop. As Reimann noted:

“It doesn’t actually follow stocks-to-use ratio. It’s not really important. We can focus on that, but we’re really looking at the wrong thing.”

So if you want to know why traders, brokers and analysts, newspapers like The Western Producer, and scribblers like me tend to talk a lot about markets outside of canola, wheat, barley and the other prairie crops, it’s because we all recognize that the biggest factor that affects those crop prices is what happens in the bigger markets.

Prairie farmers are living in a piggyback world, and to get a sense of where they’re going, they need to look at what they’re clinging tightly to.