Cycles happen. They work. They seem to be eternal. And you have to stay on top of them or you end up eating a lot of pavement.

And they’re a bit ridiculous and absurd to have to deal with, as any cyclist, hog or cattle producer knows from long and painful experience.

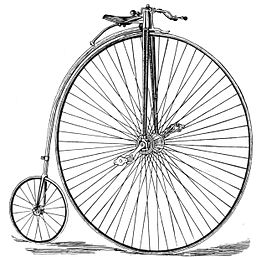

I mean, how the heck did cyclists like the one in the photograph above actually get up on top of that penny-farthing and get going, keep going and turn corners without getting killed? The device itself seems absurd, but it worked, and that’s often what you’ve gotta deal with. (I always wonder how cyclists like this one didn’t end up with three or more broken butt bones from riding on those kind of wheels, accidents or not.)

Read Also

Budget seen as fairly solid, but worrying cracks appear

The reaction from the agriculture industry to prime minister Mark Carney’s first budget handed down November 4th has been largely positive.

Hog farmers have to ride and stay atop of an approximately four-year cycle. Every once in a while the thing overturns and everyone falls off. Some land safely if they’re lucky, others get road rash and never get up again. The latter is happening to some folks right now. With cattle it’s a much longer cycle of seven to nine years, and it can have ugly over-the-handlebars accidents every once in a while. Being Canadian makes both our hog and cattle producers vulnerable to egregiously exacerbated cyclical downturns, so we tend to get far more sliding, scraping crashes than American farmers. But because the cycles are generally predictable, many producers can protect themselves from the worst, like a cyclist wearing a helmet. (I’ve lived through two cycle-car collisions. They’re not fun when you’re the dude on the bike, even if you’re wearing a helmet.)

The reason I’m thinking about crazy-looking cycles is that hog and cattle farmers right now are dealing with the craziness of their industries’ cycles, and trying to pedal through the present oily patch without hitting the Tar Macadam. Because of the extreme volatility of profitability, simple survival is going to be beyond many folks’ ability this downturn, even with golden prospects opening up from next summer onwards. The next cycle should be profitable for hog producers, especially with the North American herd shrinking, but getting there’s going to be tough, especially since the cyclical signals are encouraging farmers to breed more not less right now. That’s going to slow down the herd shrinkage that will bring about the next era of profitability. Hog and cattle producers have to deal with biological cycles of breeding, herd expansion and herd shrinkage that don’t always fit with suddenly shifted market situations, like today’s. To avoid today’s hog market crisis, farmers would have had to reduce breeding last winter and spring, when there was no good reason to do so. To make money in the next marketing cycle, they should be breeding sows right now, which seems financially perilous in the short run.

When I was talking with hog industry economists a couple of weeks ago for a special report I was writing with our Regina reporter, Karen Briere, a number of them noted the irony of the situation in which the present downturn is occurring with pigs bred during a period (last winter and spring) in which the outlook was neutral-to-positive, while during the present awful slump the outlook is even more bullish. Except through hedging, there’s little hog producers could have done with their breeding or feeding plans to mitigate the present situation. Once a sow is bred the pigtrain has left the station and will arrive in 10 months time. The outlook last spring was neutral-to-bullish due to widespread predictions of cheaper corn due to the large acreage, and the outlook for next spring and summer is bullish because of predictions of a smaller pig supply because of present herd liquidations. So pretty much throughout this mess the cyclical and price signals have encouraged farmers to breed sows and fill their barns with feeders, except for a shortish period of July to Christmas in which no one will want to be filling feeder barns. But sow barn operators, if they’re looking 10 months out, should be breeding everything they can.

This combination of cycles, with the biological cycle having trouble interacting with the present marketing reality and having trouble adapting to the revised four-year cyclical outlook puts farmers once more atop a crazily wobbly cycle, and that’s not fun to ride. But sometimes that’s the only bike you’ve got, so you’ve gotta ride it, however absurd it seems to others.