European environmental organizations were among the first to publicly advocate against the commercial introduction of genetically modified crops more than 20 years ago.

Since this time, these environmental groups have intensively lobbied to have GM crop production banned in the EU. Today, they’ve been successful in that effort, as Portugal and Spain are the only two GM crop producing countries in the EU, with less than 500,000 acres of GM corn.

Why do GM crops matter in relation to the Brazilian forest fires?

The answer is trade and land. Corn and soybeans are two vital inputs required to feed livestock. To ensure sufficient livestock feed is available to feed Europe’s livestock, the EU imports millions of tons of GM corn and soy each year. Significant volumes of imported animal feed come from Brazil. The EU imports 25 to 30 million tons of GM corn and soy annually due to its own inability to produce enough corn or soy to feed its own livestock. Currently, the EU imports 36 percent of its soybean requirements from Brazil. EU corn imports from Brazil for July and August show a three million percent increase over corn imports from last year.

Read Also

Proactive approach best bet with looming catastrophes

The Pan-Canadian Action Plan on African swine fever has been developed to avoid the worst case scenario — a total loss ofmarket access.

GM corn and soybeans benefit producers because they have higher yields and require fewer chemical inputs. GM corn has been found to have yields that can be up to 25 percent higher than non-GM varieties.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, corn production in Brazil has increased from 40 million tons to 100 million, and soybean production has increased from 75 million tons to 120 million tons. As demand for corn and soy rises in other parts of the world, Brazilian farmers see opportunities in planting more acres of both crops and will clear more land to enable higher production. The current concern over the number of forest fires burning in Brazil is that fires are in part creating more land to produce crops.

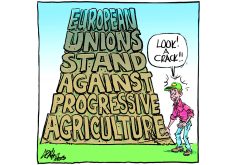

EU based anti-GMO environmental organizations have ensured that European farmers don’t have access to leading agronomic technologies, resulting in less efficient crop production. To date, these environmental organizations have had no problem pushing the lack of EU corn and soy production onto biodiverse rich, developing countries, such as Brazil. When the market for agricultural products responds as it should to increased demand, production rises. Suddenly these European environmental groups express horror and outrage at the amount of forest burning to grow more corn and soy. Oddly, it is their own domestic political activism that is partially to blame for the increased demand for corn and soy production and the resulting forest fires that will accomplish this.

Environmentalists can’t have it both ways. They can’t lobby to ban GM technologies domestically and then complain when the countries the EU imports products from don’t produce them in the way they prefer. Perhaps it’s time for EU environmental groups to reassess their opposition to GM crops.

Stuart Smyth is with the University of Saskatchewan’s agricultural and resource economics department.