As the world co-operative movement celebrates its 150th anniversary, members of the co-op community in Western Canada have had to deal with two monumental decisions by a couple of prairie giants.

Last year United Grain Growers, the Prairies’ first co-operative grain company, sold voting shares to the public. This past summer Saskatchewan Wheat Pool decided it too will offer shares publicly, although members will retain voting privileges.

Scholars at the University of Saskatchewan’s Centre for the Study of Co-operatives say that UGG is no longer a co-operative and that Saskatchewan Wheat Pool is moving in that direction. But what defines a co-op?

Read Also

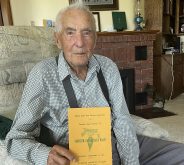

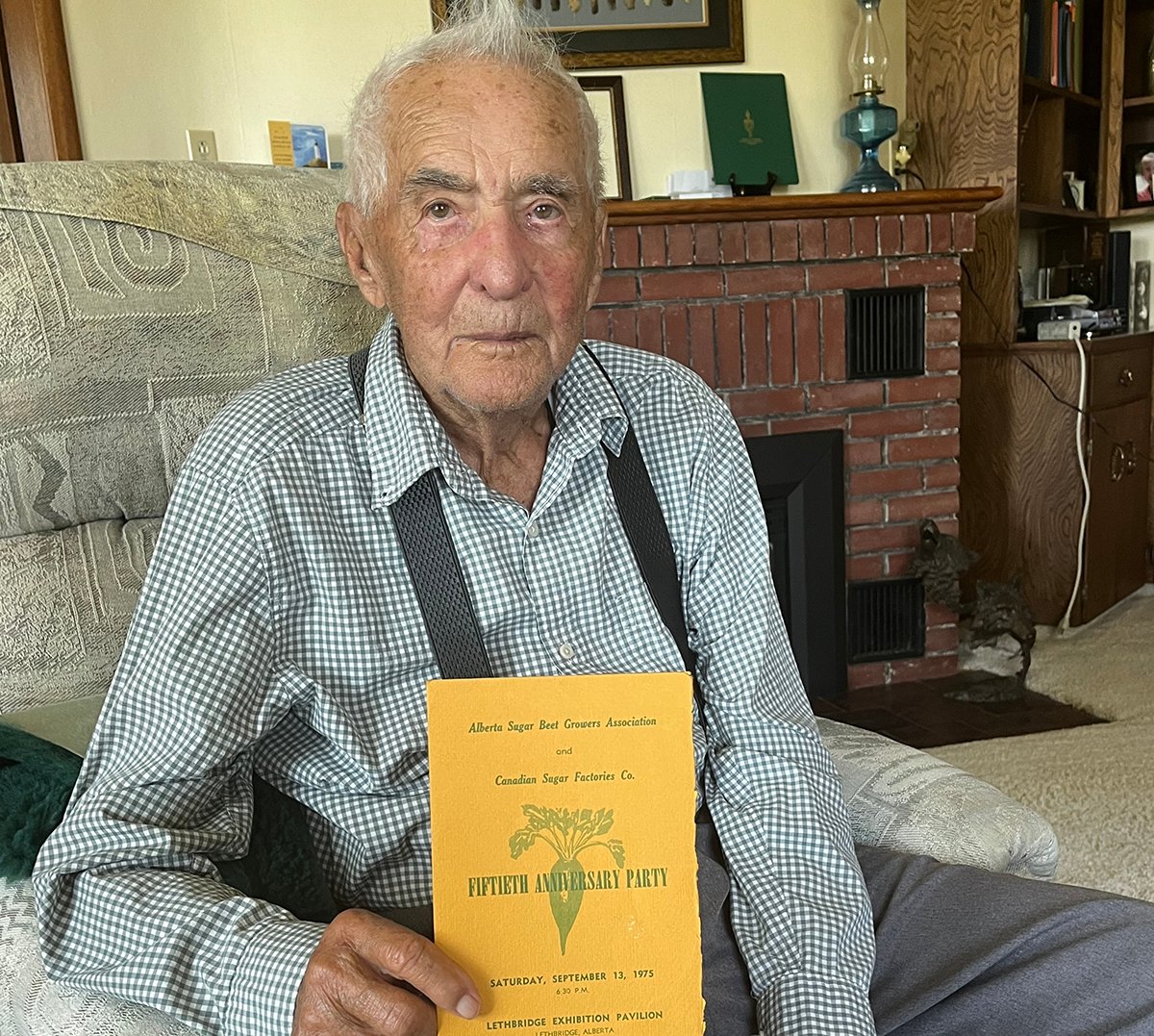

Rich life took him from sky to ground

World War II veteran Burns Wood shares some memories of his time on the Alberta Sugar Beet Growers board as the organization celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2025.

The first co-op was formed on Dec. 21, 1844 in Rochdale, England. Rochdale is thought of as the first co-operative because it was the first to successfully implement two of the fundamental principles of co-operation, said Brett Fairbairn of the Centre for the Study of Co-operatives.

“I think if you asked most people what the original Rochdale pioneers stood for, they’d come up with the ideas of democracy and of patronage refunds.”

The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers was not the first group to come up with either principle, but it was the first to effectively implement them. Democracy and patronage refunds still form the foundation of the modern co-operative movement.

As the movement evolved and word of the Rochdale experiment spread, it became clear to the Rochdale pioneers they would have to come up with a definition of what the movement was all about. In 1860 the pioneers made a statement of Rochdale’s rules of conduct called the Rochdale Practices.

In 1966, just over a century later, the International Co-operative Alliance built on these practices, forming a set of six principles known as the Rochdale Principles, which became the acid test for co-ops around the world.

The six principles are commonly referred to by the titles: Open and Voluntary Membership, Democratic Control, Limited Interest on Capital, Patronage Refunds, Co-operative Education, and Co-operation Among Co-operatives.

According to the commission that established the principles, any organization that fails any one of these tests is not a co-operative. The Centre for Co-op Studies is more relaxed in his definition of a co-op.

“Government bureaucrats and lawyers like to take a legalistic view of it, but I think in principle it’s all shades of grey,” Fairbairn said.

He sees co-ops falling somewhere along a broad spectrum that ranges from being not much of a co-op to very much a co-op.

“If it walks like a co-op and talks like a co-op, then it’s a co-op.”

Fairbairn said UGG ceased being a co-op when it changed the one-member-one-vote concept. At last fall’s annual meeting three non-farmers were elected to its 15 member board of directors.

“They have non-member directors now . . . that tips them over the edge into what most people accept is no longer a co-operative.”

He still considers Saskatchewan Wheat Pool a co-op even if patronage refunds disappear. Members can share in profits by acquiring and selling shares, but their portion of the profit no longer directly depends on how much business they do with the pool.

“What Saskatchewan Wheat Pool is proposing to do moves them over the spectrum towards being less of a co-operative. The main reason for that, in terms of traditional Rochdale analysis, is because they will no longer pay patronage refunds,” Fairbairn said.

Pool president Leroy Larsen strongly disagrees. He said the equity base put in place under the new financing will ensure the future requirements of the pool are met and make it a stronger co-operative.

But he agrees that patronage as it is now known will cease to exist under the new structure. Farmers will no longer be able to share in the profits based on how much business they do with the company. It will depend instead on how much they have invested in pool shares.

For Larsen the acid test of a co-operative is whether it remains member controlled. That’s what differentiates the Pool from UGG.

“That’s the difference and that’s where you may make the distinction of co-operative or not a co-operative,” he said. He also said there is a precedent for co-ops that start moving along the spectrum to eventually drift right off – UGG is the most recent example. In fact there is an economic theory that says this kind of progression is not unusual.

Larsen said it will be interesting to see who eventually owns the shares, but added that one of the pool’s main objectives is to make the shares attractive to current shareholders.

“It will be determined by the membership themselves whether they view this ownership as important to them by their investment in Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.”

Fairbairn said the co-operative community was taken aback by Sask Pool’s decision to go public, but he said it’s difficult to get anyone to admit it.

Sid Bildfell, chief executive officer of Credit Union Central, said he was not surprised by the pool’s action. He said co-operatives need to be strong to be competitive, the pool was simply strengthening its financial position. He still considers the pool to be a strong co-operative.

“What I’ve seen and read, they’ve been spending a tremendous amount of time talking to their owners and discussing the issues. If that’s not a co-operative I don’t know what is.”

Bildfell said the world has changed dramatically since the days of Rochdale and co-ops have changed with it. Although the pool no longer has patronage refunds, thefarmer/

owner can still participate in decisions by electing members to the board and share in profits by buying and selling shares on the exchange or through rebate programs.

As far as Bildfell is concerned, the pool hasn’t compromised any of its co-operative principles with the public share offering.

Top 50 list

The 1993 list of the Top 50 Canadian co-operatives has Federated Co-operatives Ltd., located in Saskatoon, in first position, moving the 1992 winner, Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, into second place.

With revenue of $14.3 billion in 1993, the Top 50 co-operatives gained 2.2 percent from the previous year. Ten co-ops had a growth of more than 10 percent in sales and service revenue including four outstanding companies. These were: Mountain Equipment Co-operative (39.7%) and Western Greenhouse Growers’ Co-operative (37.2%) from British Columbia, XCAN Grain Pool Ltd. from Manitoba (35.3%) and Co-op Centre Ltd. from New Brunswick (24.4%). Federated Co-operatives Ltd. had the highest dollar increase in 1993 at $223.5 million.

Assets were up by 3.6 percent at $4.84 billion, due mainly to increased inventories in the grain marketing co-operatives and inclusion for the first time of Arifoods International Cooperative Ltd. a dairy co-operative from western Canada, which ranked seventh in terms of assets.

Seventy-five percent of the co-operatives included in the Top 50 list are producers’ co-operatives which provide agri-supply or commodity marketing to members. The balance are consumer co-operatives with activities mainly in grocery, consumer goods, recreational equipment and health services.

The Top 50 co-operatives employed 33,301 full-time and part-time employees, a two percent reduction over the 1992 results. CoopŽrative fŽdŽrŽe de QuŽbec was the largest non-financial co-operative employer in Canada with more than 5,000 employees.

The 1993 list includes 45 co-operatives from the previous Top 50 list. The five new co-operatives are Agrifoods International Cooperative, XCAN Grain Pool Ltd., Island Farms Dairy Co-operative Association, SociŽtŽ coopŽrative avicole rŽgionale de Saint-Damase and Western Greenhouse Growers’ Association.

This is the 10th edition of the Top 50 list published by the Co-operatives Secretariat. It does not include financial co-operatives, such as credit unions, caisses populaires, trusts and insurance co-operatives.