The newspaper looks back at a century of providing prairie farmers a voice in the Canadian agriculture industry and serving as an educational platform for the entire family

It was an emergency.

The founders of this newspaper were deeply involved in a debate that roiled the farm population in summer 1923: should a co-operative pool be formed to market farmers’ wheat?

Saskatchewan Co-operative Wheat Producers Ltd., what became Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, had until the end of Sept. 12 to persuade farmers with 50 percent of the province’s acres to sign a contract to let the pool market their grain.

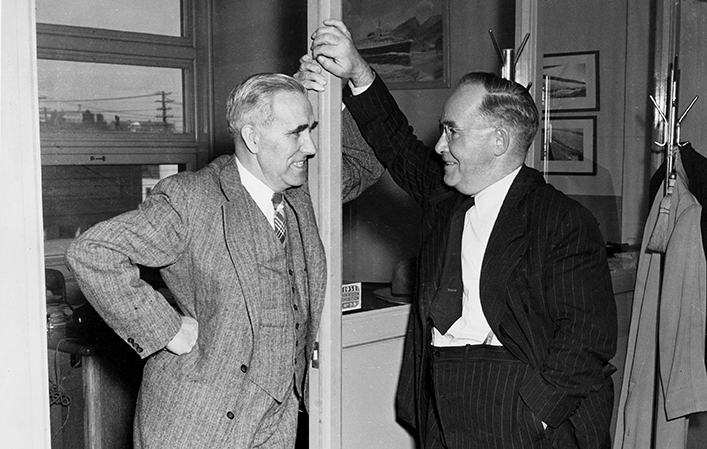

Harris Turner and Pat Waldron, First World War veterans with journalism and publishing backgrounds, were interested in progressive ideas generated in the aftermath of the war and they owned a printing press.

The co-operative wheat selling idea captured their attention and the growing farm population of Saskatchewan would provide an audience for the type of paper they wanted to produce.

So on Aug. 27, 1923, with financial support from the pro-pool Saskatchewan Grain Growers Association (SGGA), they rushed to print the first issue of The Progressive.

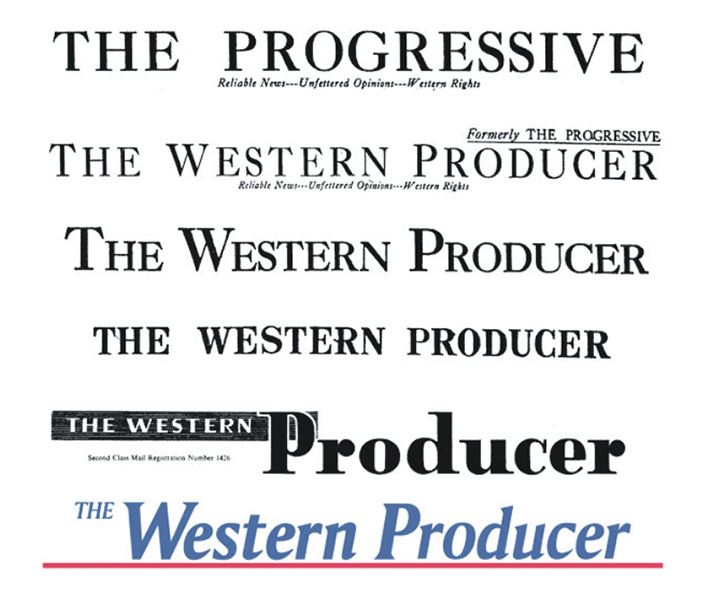

The front page of that first issue carried an editorial with the headline Emergency Issue supporting a wheat pool, but promised that with more time and organization, the publication would become a full-fledged paper filled with “Reliable News, Unfettered Options, Western Rights.”

Even with that effort, the pool sign-up effort failed.

But advocates didn’t give up. Nor did Turner and Waldron.

Through 1923 and into 1924 Pool advocates promoted the concept, as did The Progressive’s editorials, and by June 16 they reached the 50 percent of acreage target to form a voluntary marketing pool.

The SGGA had provided a $7,000 loan to The Progressive and encouraged members to buy a subscription. The SGGA had representation on the newspaper’s editorial board, and had guaranteed space for SGGA news, but also agreed to make space for news for the rival Saskatchewan Farmers Union.

With the sign up target met, the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool came into being. Turner and Waldron asked the new organization to become the paper’s sponsor.

SWP wanted to be non-partisan and wanted the paper to change its name to avoid association with the Progressive political party, a movement in the 1920s with strong farmer support.

Turner was a member of the legislature, elected in 1917 as a representative of soldiers fighting in Europe.

He had been a witty and popular newspaper columnist in Saskatoon before signing up and going overseas in 1915. Shrapnel blinded him in both eyes during the Battle of Mount Sorrel and he was sent home. Soon after, the province decided its serving men deserved a representative in government.

At a meeting of soldiers to find a candidate to put forward, Turner met an Irish-born fellow journalist who had also been wounded, Pat Waldron.

Waldron became Turner’s successful campaign manager and the two became lifelong friends.

They bought a printing press, named it Modern Press, and started their first venture, Turner’s Weekly, but it failed in 1920.

To make the press a success, it needed a large newspaper to print.

The interests of Turner, Waldron and the Pool proponents all came together at the right time to launch a paper of interest to farmers.

As Waldron stated in an interview on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of The Western Producer:

“The whole farm campaign was something akin to an evangelical movement. We were all like brothers striving toward the same end.”

In September 1924, on the request of SWP, The Progressive changed its name to The Western Producer.

Turner still sat as an independent in the legislature and even became leader of the opposition in 1925. He ran in the 1925 election as a Progressive, but lost. He then concentrated full time on the newspaper, which had become what it promised in the first issue of The Progressive. It carried news from home and abroad, editorial commentary, letters to the editor, humour, markets, advertising, features for women and for “junior grain growers.”

The paper reflected the turbulent and transformative years of the 1920s.

The world was still mending from the First World War.

Women had recently won the vote and many pushed for a more active role in society.

Young people hoped for more independence and self-expression.

However, Canadian prairie farm families remained isolated. Few had electricity. Work was hard.

The Producer’s founders knew that to build circulation, it needed to connect with the whole farm family.

Perhaps their best step was to hire, as associate editor, Violet McNaughton, a tiny woman, shy of five feet tall, who loomed large in prairie social history.

McNaughton had led the woman’s branch of the Saskatchewan Grain Growers, promoted women’s suffrage and campaigned for trained midwives and accessible health care.

Under her guidance, the women’s pages of the paper became a valued source of information and communication for rural families.

As former Western Producer editor Garry Fairbairn wrote in his history of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, From Prairie Roots: “As she worked for women’s rights, regional hospitals, schools for the deaf and a hundred other causes, she built up a network of correspondents and fans that amounted to an invisible social-reform movement and included virtually every prominent figure in prairie social reform.”

She introduced pages for “Juniors at work, Juniors at play” and the Young Co-operator’s club.

McNaughton was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1934.

This connection with the whole family gave a strong argument for the paper to attract advertising dollars, as in this self-promotion notice:

“In 1943, more than 53,000 rural women sent to the Western Producer for patterns, embroidery services or home service booklets. Every order had cash enclosed.”

The newspaper had to be indispensable to the farm family because revenue was not assured.

Subscriptions in the early years were funded by deduction from Pool interim payments. But as grain prices collapsed in late 1929, there were no interim payments and no money for subscriptions.

The paper would fail unless Saskatchewan Wheat Pool took it over, which it did in 1931.

Turner, whose health was not good, soon left the business, but retained a column for 26 years.

Waldron took over as managing editor, remaining at the helm until retirement in 1958.

In the early 1930s, the paper’s editorials still advocated for a government-run marketing board. The Central Selling agency of the three Pools had almost collapsed with the crash of grain prices.

But the Producer welcomed all opinions on the letters to the editor pages, and the lively debates that dominated the farm community were on full display.

In the summer of 1935, the Producer carried news of the unemployed in the On To Ottawa trek and the Regina Riot. And then there was the momentous news that Parliament had passed a bill creating the Canadian Wheat Board.

Surprisingly, the editorial was muted: “All things considered, it is a reasonably satisfactory piece of legislation.”

Editorials focused more on the need for a substantial government-guaranteed minimum price for wheat and to protect farmers from creditors.

As the 1930s progressed, the Producer averaged around 32 pages and was widening its offering.

In the summer, it produced a weekly crop report. There was little information about improving production practices but there were features on livestock husbandry and beekeeping.

A page was devoted to radio and another to sports with scores from American baseball leagues and British soccer.

Ads for tractors were common and occasionally retailers would promote special sales, like John Christie’s surplus British army blankets at $1.80, all wool underwear for $1.95 and “warm auto robes” for $3.45.

As the Second World War began, the Producer stepped up coverage of international events, including maps of theatres of war and battles.

With Canada on a war footing, the CWB’s role expanded. The government suspended the Winnipeg Grain Exchange in September 1943, giving the CWB a monopoly.

The Producer’s editorial supported the move and recommended that, in charting the path forward, the government should listen to the advice of the prairie Pools because of their experience, democratic nature and farmer management.

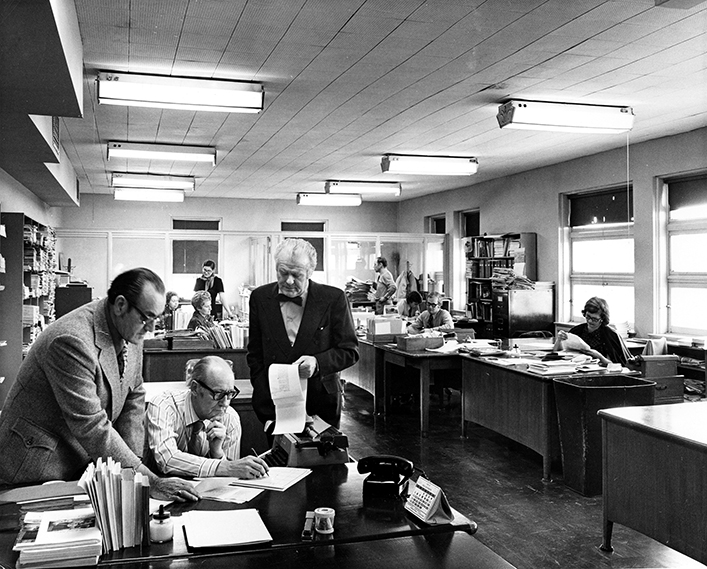

In the post-war era, the Producer again expanded, doubling its printing capacity and its editorial ambitions.

For the first time, reporters occasionally received bylines.

A magazine section delivered longer stories such as a trip to Churchill, Man., to see the port grain elevator.

The full pages formerly given over to SWP information disappeared but co-ops still had dedicated features.

The classified advertising pages, for which the Producer would become famous, increased.

In 1952 “Rusty” MacDonald became executive editor and in discussions with Waldron decided to “Canadianize” the paper, as MacDonald recalled in a 1973 anniversary story.

That meant ending serialized fiction from Americans and Britons and replacing it with material written by Canadians.

Columns appeared such as Doc Savage Says on animal health, Doug Gilroy on prairie wildlife and How Are You? with Dr. Marcus Hayes.

By the end of the 1950s, the paper was 48 pages and it devoted another 30 to the magazine.

In 1959, grain prices again crashed and farm organizations planned a new march on Ottawa to demand deficiency payments.

Producer editor Tom Melville-Ness and reporter Keith Dryden travelled with hundreds of farmers on the special protest trains.

They sent back reports to the paper and even produced a daily newsletter for the thousand-plus farmer demonstrators.

In the 1960s, the front page news about events overseas was disappearing, replaced with coverage of Canadian matters.

The magazine was renamed Photocolor with light features and in-depth coverage, such as a piece in 1965 titled Rapeseed Development Exciting Experience, and a three-part package on communities affected by the new dam on the South Saskatchewan River.

Advertisements for herbicides, such as Carbyne for wild oats, appeared.

To attract subscribers, the paper for a time introduced the Alberta Producer, with columnists from Calgary, Lethbridge and the Peace River Country.

The old guard was passing on.

Violet McNaughton retired in 1950.

Harris Turner died in Victoria in 1972 at age 84, while Waldron died in Saskatoon in 1980 at age 90.

New people made their mark. Rose Jardine took the reins of the Women’s Pages, including writing a popular gardening column. Her sister, Emmie Oddie, soon joined with a question and answer column on home economics and practical advice called “I’d Like to Know”, which ran from 1949 to 1995.

By 1970, the Women’s Pages had become Mainly For Women.

The Young Co-operators pages continued, providing a venue for youth to showcase their writings and find pen pals.

There were TV schedules for CBC and CTV.

The popularity of the classified ads grew and the personal ads provided a place for lonely farmers to seek correspondence with potential partners. “Snap exchanged. Matrimony if suited.”

Celebrating its 50th anniversary in 1973, the paper boasted a paid subscription of 150,000, including 80,000 in Saskatchewan, 40,000 in Alberta and 17,000 in Manitoba.

The paper was still a crucial forum for debate, publishing almost 300 letters to the editor during the year.

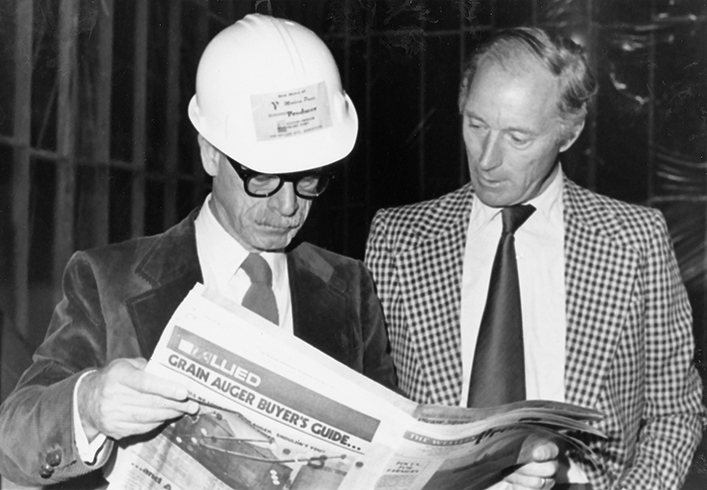

In 1977, the paper and Modern Press moved from central Saskatoon to a large building in the north industrial area.

In 1978, the paper launched “the little magazine”, Western People, with pages half the size of the tabloid newspaper.

Farming became more complex and the range of inputs from herbicides to fertilizer to seeds was exploding. These products needed exposure and the Producer was a great place to advertise. The new ads funded the paper’s expansion.

In spring, there were two sections each with 64 pages. The B section had more than 40 pages of classifieds.

Bob Phillips was the editor and publisher and Keith Dryden had become executive editor.

They further modernized the paper, including hiring a larger, more professional reporting staff and opening bureaus.

Familiar bylines appeared. There were staff reporters in Winnipeg, Regina and Alberta and Barry Wilson in Ottawa. Adrian Ewins began a long career covering the grain industry.

The Mainly For Women section evolved into Western Living under Liz Delahey’s editorship but there was still room for the Young Co-operators.

In 1987, following a torrential June rain, the roof of the Producer-Modern Press building collapsed.

No one was hurt, but there were problems with the insurance payout. Compounding the problem, a string of droughts and poor grain prices slashed revenue. Losses had to be covered by SWP.

The financial stress led to staff cuts and other economies like moving Western People inside the paper.

With better finances in 1995, it returned in the “little magazine” format, but with declining membership the Young Co-operators club took its final bow, replaced by features called KidSpin.

Garry Fairbairn, editor since 1991, worked to keep the editorial department on the leading edge of newspaper technology.

In 1995, the paper launched itself onto the internet, a year before much bigger papers such as the New York Times.

Fairbairn and Wilson were among the newspaper’s journalists who wrote books on Canadian agriculture.

Fairbairn’s history of the SWP was published in 1984 by Western Producer Prairie Books, which had its origins in 1954. Its assets were sold as part of the 1991 belt tightening.

Elaine Shein, an enthusiastic member of the Young Co-operators club as a child, pursued journalism as a career and joined the Producer staff. She became editor in 1997, beginning a long stretch of women guiding the news and editorial side of the business, including Barb Glen and Joanne Paulson.

In the 1990s, farmers running sophisticated operations said they wanted more in-depth information on production and markets.

Designated sections for these topics expanded and the paper published special supplements to delve deeply into the management of canola, pulse and special crops, alternative livestock and seed guides.

Farming Magazine took production information to a new level of sophistication with high gloss paper and specialized reporters.

The paper opened bureaus in Brandon and Camrose and for a while regionally tailored news presentation with separate Alberta-British Columbia. and Saskatchewan-Manitoba editions.

In 1998, the paper’s 75th anniversary, it had 51,335 subscribers in Saskatchewan, 26,433 in Alberta, 8,474 in Manitoba, 7,070 in British Columbia and about 2,000 elsewhere.

The prairie grain sector saw great change, providing lots of news to cover and analyze.

Saskatchewan Wheat Pool ended its co-op status and became a publicly traded company in 1996.

It and other grain companies spent billions to transform their grain-handling networks. But low grain prices again caused losses and big debts.

SWP trimmed down to its core grain business, selling its other divisions.

In December 2001, GVIC Communications Inc., owned by Glacier Ventures International Corp. headquartered in Vancouver, bought the Producer for $12 million.

GVIC went on to buy most farm publications in Canada, including the Manitoba Co-operator, Grainews, Farmers Independent Weekly and Country Guide. It now manages them all under Glacier FarmMedia.

However, it was mostly business as usual at the Producer.

In 2009, the first redesign in 17 years introduced the now-familiar blue flag.

The Producer’s former full-throated support on the editorial page of orderly marketing had long since disappeared.

When in 2012 legislation passed ending the CWB’s single desk, there was a front-page story and a two-page spread inside with industry reaction and a review of the board’s history. But there was no editorial comment about the development.

In recent years, the Producer, like all newspapers, has faced overwhelming competition from the internet for advertising revenue and circulation, which is reflected in the decline in farm numbers.

Printing shifted to Glacier’s press in Estevan, Sask., in 2015.

However, the paper and its website have coped better than many publications and has maintained a strong news operation by concentrating on the needs of its readers.

It could justifiably restate the words that appeared in a notice in 1926 marking the beginning of its third year:

“A Hope Realized — A Promise Fulfilled — An Experiment Justified.”