SUMY, Ukraine – The Massey Ferguson combine churns down one side of a field of soybeans.

A John Deere makes short work of the other side.

Harvest has just about wound down here in late October. A few fields of soybeans and sunflowers remain while others are green with fall-seeded wheat and canola.

It’s an agricultural tableau familiar to North Americans.

However, several kilometres down the road the picture is different.

A farmer is cleaning his old plow’s depth leveller, a small wheel attached to the frame to help control furrow depth. The thick black soil has packed in tightly and the wheel won’t turn.

Read Also

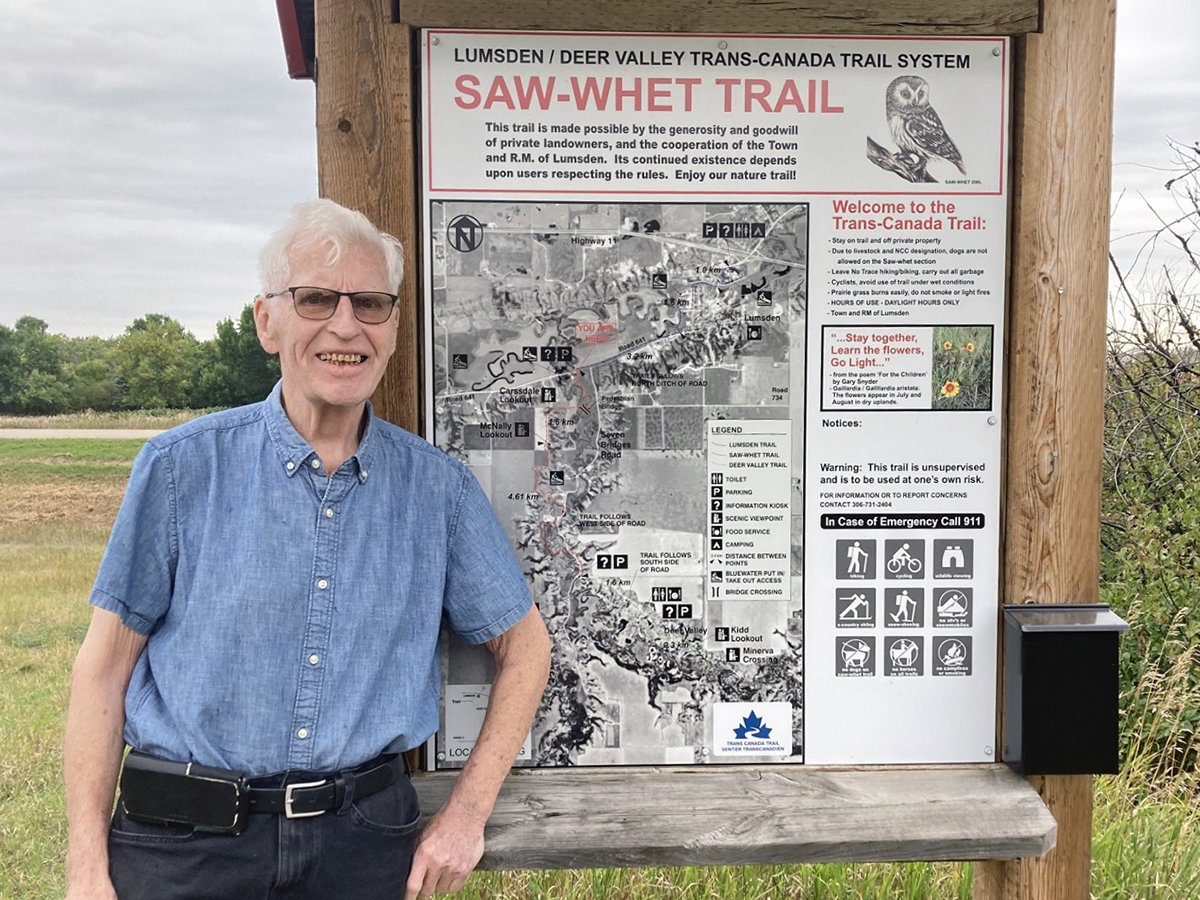

‘Sinc’ remembered for dedication to rural Saskatchewan

A rural Saskatchewan leader instantly recognized by just his first name is being remembered for his dedication to the province.

The plow has just five plowshares; the tractor is old and progress is slow.

The contrast characterizes grain farming in Ukraine today as the industry adapts to life post-Soviet Union.

While some landowners have attracted investors and imported modern technology, others struggle with machinery that most North Americans abandoned long ago.

Still, Ukraine produced 53.3 million tonnes of grain in 2008, compared to 72.6 million in Canada, of which 58 million came from Western Canada.

The harvest was the largest since Ukraine became independent in August 1991. However, the country has yet to produce what it did as the breadbasket of the Soviet Union.

Production is a moving target for many reasons, including weather, pests, poor management and lack of technology. Yields are about half those of other European countries.

Quality issues keep Ukraine grain out of markets that could earn farmers more money.

The industry will develop but it will take a long time, said Mykhailo Dmytrushko, a farmer who is also president of the Association of Farmers of Sumy administrative region.

“We have all possibilities in Ukraine,” he said through a translator. “It’s a reform process.”

Observers agree Ukraine’s potential is immense. It has a climate conducive to agriculture and one-third of the world’s richest black soil.

But its farmers and agricultural infrastucture have a long way to go.

The road and rail systems and the vehicles that travel on them need upgrading. Storage facilities are lacking or need improvement.

Some work has been done to expand capacity at the Black Sea ports.

“We have indications they have been modernizing,” said a senior grain analyst at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “My question is, how far back has that gone?”

There are also political concerns.

There are ongoing power struggles within Ukraine’s parliament, and the global financial crisis doesn’t help.

Policies and laws that could be implemented to help the agricultural sector have taken a back seat to the drama.

Seventeen years into reform, farmers face a lack of stable financing, a non-existent land market and a taxation policy they think is too expensive, Dmytrushko said.

Like their counterparts around the world, Ukrainian farmers are struggling with rising input costs and low commodity prices. This year’s large wheat crop is about 70 percent feed quality; the price is low and so is demand.

“This year we have a serious crisis in agriculture,” Dmytrushko said.

“We can’t pay everything and farmers are near bankruptcy.”

Few farmers have access to credit, although government loans are available.

“Banks are not very enthusiastic,” said Gennadiy Vorobyov of Farmer magazine, a Ukrainian agricultural publication. “It’s a risky business.”

This limits the ability to buy fertilizer and produce a quality crop.

Non-repayable farm aid is limited to new farmers who have been in the business less than three years, Dmytrushko said, and most think that isn’t enough time to become established.

Farmers pay a fixed agricultural tax based on assessed land value, but because farm land can’t be bought or sold, the value is set by local authorities based on the land type and quality.

The adjustment from a planned economy has been rough.

Ukraine was the most agrarian of the former Soviet republics. Under the Soviet system, surplus grain was shipped within the union and imports covered shortages.

That changed when the Soviet Union disintegrated.

Ukraine’s agricultural gross domestic product dropped by 51 percent between 1991 and 1999, according to a study by the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

It recovered slightly at the turn of the century but fell again by 18 percent in 2003.

“This economic decline has been one of the most severe and prolonged in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union,” said the study.

“Some of this decline was the result of a collapse in the general economy, but this recession was made deeper and longer than in other transition economies by slow and inconsistent policy reforms for most of the 1990s.”

Reforms introduced since 1999 caused some improvement, but farming is still a challenging business made more difficult by either government inactivity or intervention through mechanisms like export quotas.

“They are optimistic,” Vorobyov said of the farmers he talks with. “But they know they will get no support from their government.”

Farmers look increasingly to the export market to generate returns.

“Ukraine has become a rather aggressive export competitor,” said Bruce Burnett, director of weather and market analysis at the Canadian Wheat Board.

Ukraine’s low protein winter wheat does not compete directly with Canada’s hard spring wheat, but the volume of wheat the former Soviet republics can produce affects markets.

“One of the things that drove the market upward last year was the lack of grain available in the Black Sea region,” he said.

The USDA analyst said Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan have traditionally produced about nine million tonnes for the export market, or almost seven percent of world wheat trade.

“The upside potential is tremendous, but the reality of the situation would seem to constrain it.”