Canadian official says Health Canada takes into account exposure to vulnerable people before products are approved

A study out of the University of California is linking heavy pesticide use in farmers’ fields to birth defects in surrounding communities.

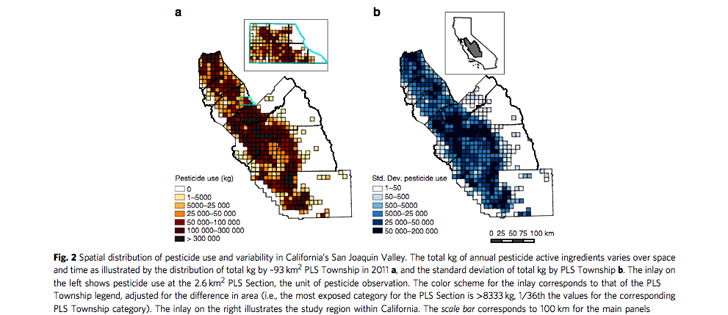

Researchers looked at more than 500,000 birth records between 1997 and 2011 in the San Joaquin Valley of California, which is a region that grows a lot of high value fruits and vegetables.

The study, which was published in the Nature Communications journal (PDF format), said great advances have been made in understanding the effects of smoking and air pollution on births but research on the effects of pesticides has been inconclusive.

Read Also

Saskatchewan dairy farm breeds international champion

A Saskatchewan bred cow made history at the 2025 World Dairy Expo in Madison, Wisconsin, when she was named grand champion in the five-year-old Holstein class.

That is because while smoking is observable and there are robust networks to monitor air pollution, publicly available pesticide use data is hard to come by.

But in the San Joaquin Valley, researchers were able to access vast pesticide and birth data enabling them to determine whether pesticide exposure had an impact on birth outcomes.

And the answer is that it did but only when pregnant women were exposed to very high quantities of pesticides. For most births in the valley, there was no statistically identifiable impact of pesticide exposure on birth outcomes.

However, for expectant mothers in the top five percent of exposure, it led to a five to nine percent increase in adverse outcomes, including low birth weights, premature births and defects.

“For perspective, other environmental conditions such as air pollution and extreme heat generally report a five to 10 percent increase in adverse birth outcomes but from less extreme exposure,” stated the abstract of the study.

Pierre Petelle, president of Crop-Life Canada, hasn’t had time to review the study in detail but at first glance there appears to be some fundamental flaws.

“They’re assuming that pesticide use equates to pesticide exposure, which is not necessarily the case,” he said.

The study also mentions that air pollution and extreme heat affect birth outcomes by about the same percentage as heavy pesticide use, but the study doesn’t seem to control for those factors.

Petelle points out that Health Canada looks at the worst case scenario when approving pesticides and pays special attention to pregnant women.

“The Pest Control Products Act in Canada has special provisions for the protection of pregnant women and children, which is laid out right in the legislation, so that is taken into account during the risk assessment,” he said.

Petelle believes a better study is the Agricultural Health Study, which has been tracking 89,000 U.S. farmers, their spouses and offspring for the past 24 years.

“There has never been any real correlation between pesticide users and negative health outcomes,” he said.

However, a summary of the findings on the study’s website stated farmers have a higher risk of developing some cancers, rotenone and paraquat are linked to increased likelihood of contracting Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes and thyroid disease risk may increase for users of some organochlorine chemicals.

Petelle also noted that the chemical use on the fruit and tree nuts grown in the San Joaquin Valley would be much higher than what is used on grain and oilseed farms on the Canadian Prairies.

In the study, the top fifth percentile of exposure amounted to 4,200 kilograms of pesticides applied within a 2.6 kilometre radius of the mother’s residence during her nine-month gestation period.

The study authors said government policies aimed at curbing that top fifth percentile of pesticide distribution near human habitation could largely eliminate adverse birth outcomes.

The study did not isolate what role individual chemicals have on birth outcomes because they are often used in conjunction with other chemicals or applied in close proximity.

Lead author Ashley Larsen said it is difficult to say whether the findings of this study would apply to grain farms in Western Canada.

On one hand, the concentration of pesticides applied to a wheat or canola crop would be far less than what farmers in the San Joaquin Valley apply to their almond, grape, carrot or strawberry crops.

“I would guess it’s one-fifth to one-tenth the amount of active ingredient,” she said.

On the other hand, an expectant mother living on a farm may have more direct contact with pesticides than the mothers in the California study who were living in nearby communities and were exposed to spray drift or dust.

Larsen said it also depends on what type of chemical is being applied on grain farms because some have no effect on reproductive risk while others have a significant impact.