If you walk out of your house and see the window of the garage is smashed, do you report it to the police?

The answer may depend on where you live. If you live in a big city — probably. If you live on a farm in Western Canada — probably not.

In the Rural Municipality of Blaine Lake in north-central Saskatchewan, many landowners and farmers no longer report things like broken windows because they’ve lost faith in the police and the justice system, said Reeve William Chalmers.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“In the RM of Blaine Lake the thought process when things go missing or fuel goes missing … a lot of people have given up on reporting those crimes,” he said.

The RM has even stopped reporting some crimes on its own municipal property. Chalmers said there’s been a rash of vandals shooting and damaging municipal signs in the area, but there’s no point in reporting it to the police.

“(But) each incident is a crime.”

In a world where mass shootings of children are now commonplace, damage to signs and broken windows in rural parts of Canada can seem like minor incidents, maybe even irrelevant.

But there’s another school of thought.

In the 1990s, the New York Police Department adopted a policing philosophy known as the Broken Windows model, where officers arrested people for minor crimes such as avoiding subway fares.

In a 2015 article in the New York Post, former NYPD police Commissioner Bill Bratton said the idea behind Broken Windows was to stop low-level crime before it flourished and evolved into more serious crime. In his words, “unaddressed disorder encourages more disorder.”

Bratton and other policing experts claim that Broken Windows, or zero tolerance for minor crimes, was responsible for dramatically reducing rates of assault, robbery and other major crimes in New York during the 1990s and 2000s.

Sociologists and criminologists continue to debate the merits of Broken Windows. Bratton, though, remains convinced that it’s essential to policing.

“(We) should never and must never retreat from enforcing the law,” Bratton wrote in the Post, adding the approach enhances overall quality of life.

Broken Windows may have caught on in major cities like New York, but aggressively pursuing criminals for minor crimes doesn’t seem to be a policing philosophy in places like Blaine Lake.

Chalmers said RCMP officers, when they respond to a property crime on a farm, often say things that are the opposite of Broken Windows.

“They make a comment that, ‘gee, I hope you’ve got insurance because we’re never going to find any of this stuff,’ before they even ask your name,” he said.

“That’s concerning that the RCMP feel there’s very little they can do to help the landowner.”

Mabel Hamilton, a rancher who runs Bevin Angus with her husband Gavin and their children near Innisfail, Alta., hasn’t lost confidence in the RCMP.

She believes that RCMP officers do conduct thorough investigations of property crimes, but the justice system fails to prosecute the criminals.

Over the last few years her son’s house has been broken into twice and two vehicles have been stolen from the farm. As well, criminals have tried to steal fuel and break into machine shops.

The stolen vehicles had OnStar, a navigation system where it’s possible to turn off the vehicle’s engine from a central location.

“The woman who stole it, they (OnStar) shut the truck down and she was in it. That’s pretty clear that she was guilty,” Hamilton said.

However, when the case finally got to court, after more than a year of delays, the car thief got a six month sentence.

“Which will not be six months,” Hamilton said.

“They (RCMP) do their part … (but) to me the system is broken, and that’s what most of us in the rural communities feel.”

Hamilton isn’t the only rural resident who has lost faith in the justice system.

This January in an online discussion posted on Reddit Saskatchewan, numerous rural landowners raged against the lack of action on property crimes. One commenter mentioned a broken window:

- “Car window was busted on my days off. Some meth head spotted my safety ticket wallet and figured it was a score. Was told to go through SGI (Sask auto insurance) for the window and that nothing was going to be done other than a quick case note for records.”

- Another person on the site sympathized, adding that more police officers and more charges won’t solve the problem: “It would also be nice to have all these repeat offenders caught for thefts and break and enters get a serious punishment in court. It is a pain mentally to catch people with four-page-long criminal records and all they get is a piece of paper telling them to behave or a month in jail.”

Chalmers, who is critical of the RCMP, agreed that the court system deters and discourages effective policing.

“A lot of the criminals they’re catching are career criminals. They put them away and they (the police) say things should calm down for at least three months because that’s what they got sentenced to. But in three and a half months you can expect much the same,” Chalmers said.

“We’ve got a broken system. There’s no doubt about it.”

Canadians will inevitably be unhappy with the outcome of a particular criminal case or feel a verdict was unjust, said Dale Eisler, senior policy fellow with the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Regina, but that doesn’t mean Canada’s criminal court system is broken.

“Criticizing the judicial system, the courts system, I think is a dangerous road to go down,” he said.

“We have to assume that the criminal justice system acts responsibly.”

Eisler said the decision in this winter’s highly publicized case of Saskatchewan farmer Gerald Stanley, who was found not guilty of second degree murder in the death of Colten Boushie, a young indigenous man, is an example of condemning the entire court system based on one case without all the information about that case.

“I can understand why people were upset by it … but how do you make the determination (about the verdict) if you weren’t there to hear all the evidence and (there) in the jury room to see how the evidence was discussed and weighed?” he said.

As for the Broken Windows model, Eisler said it might be appropriate for New York City but the RCMP in rural Canada doesn’t have the capacity and manpower to deal with every property crime.

More importantly, would arresting more people for minor crimes actually accomplish anything? Instead, maybe society should dedicate more money and time to deal with the underlying causes of crime.

“Crime is a symptom of some other problem,” said Eisler. “What are the social issues that lead to criminal behaviour, how can you address them at an earlier stage?”

Bill Gehl, who farms near Regina, made a similar comment: yes, property crime is an issue in rural Saskatchewan, but farmers need to think about the bigger picture.

“Crime, to me, is usually an indication of poverty and drug abuse,” he said.

“If you go into areas where crime is bad, you’re going to see poverty and problems with addictions.”

Eisler, who last year wrote a policy paper on crime in Saskatchewan for the Johnson Shoyama school of public policy, said at some point politicians and community leaders need to have a real conversation about a difficult and unpleasant fact: indigenous people in Saskatchewan are 33 times more likely to be incarcerated than the rest of the population.

“To put that in perspective, in the U.S,. black men are six times more likely to be imprisoned than white men.”

The ups and downs of property crime

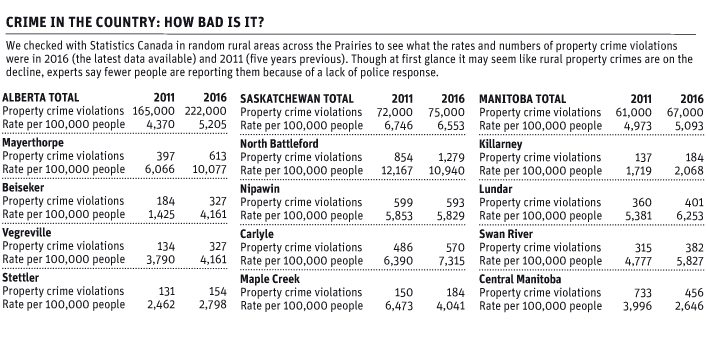

Statistics Canada tracks crime data and breaks it down into types of crime, such as property crime violations. Here are some of the statistics:

- The number of property crimes in Alberta was basically the same in 2015-16: 217,481 in 2015 and 221,390 in 2016. Taking into account an increasing population, the change was 0.04 percent.

- In Claresholm, Alta., south of Calgary, the story was much different. There, the number of property crimes jumped from 277 in 2015 to 375 in 2016. This was an increase of 27 percent, factoring in population changes. The year-over-year increase could be dismissed as a random event, but property crime data from many rural areas of the Prairies suggest it isn’t random.

- In the area around Mayerthorpe, Alta., the number of property crimes increased every year from 2010 to 2016, going from 316 in 2010 to 613 in 2016.

- In the rural region near Melville, Sask., there were 325 property crime violations in 2010 and 544 in 2016.

- Around Carlyle, Sask., property crimes jumped from 358 in 2013 to 570 in 2016.

- Property crime rates spiked in parts of the Prairies in 2015 and 2016, particularly in Alberta, but longer-term data from 2001-16 tells a different story.

- In Nipawin, Sask., Killarney, Man. and other regions of Western Canada, the rate of rural property crime hasn’t changed significantly over the last 15 years. However, the actual number of property crimes is likely much higher than reported. A Statistics Canada document from 2013 estimated that only one-third of all crimes are reported.

Want to check crime stats for your area?

Alberta: bit.ly/2EYxtaJ

Sask.: bit.ly/2BMwb0n

Manitoba: bit.ly/2GHmQpJ

• Click on the “Add/Remove Data” tab to find crime stats for a town or municipality. Follow the steps to focus on geographic area, type of crime, type of statistics and the time frame you’re interested in. Finally, click on “apply” to generate your data.