Clubroot is not well established in wide swaths of farmland in Saskatchewan, unlike regions of Alberta and Manitoba.

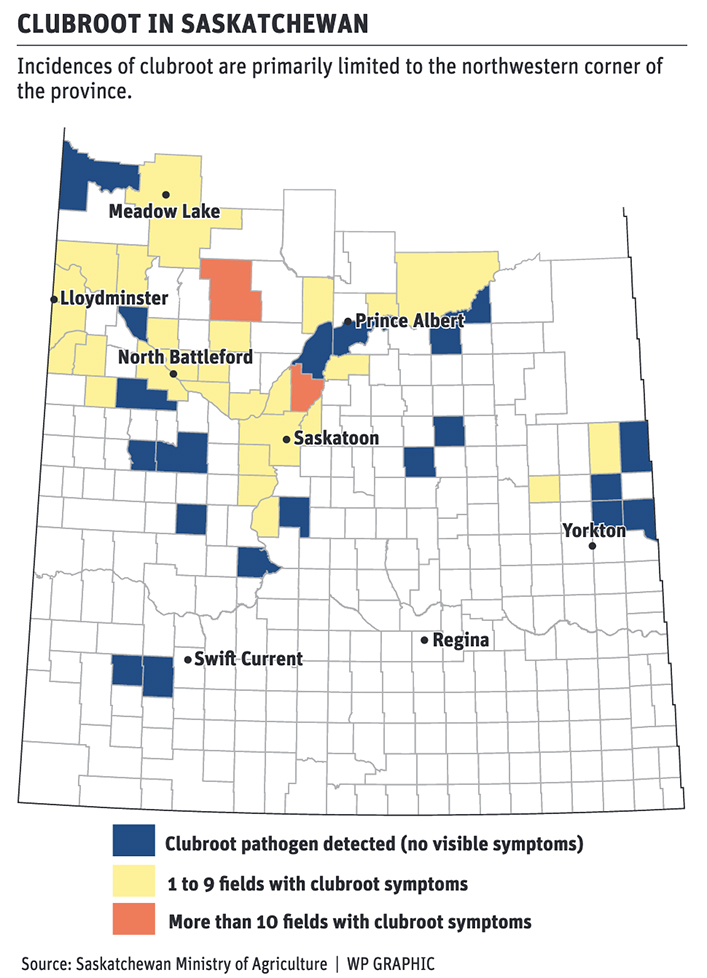

The Saskatchewan government annually releases its clubroot distribution map that outlines rural municipalities where clubroot has been identified. Clubroot is a soil-borne disease that can cause significant canola yield loss when pathogen levels are high.

“This year, we had visible symptoms only in two more commercial canola fields, and also the pathogens’ DNA was found in only four new fields. All together we have six new fields this year, two for visible symptoms and four for pathogen DNA, which in general suggests a low spread of the clubroot pathogen,” said provincial plant disease specialist Alireza Akhavan.

“If we divide the six new fields we found with the 521 fields we surveyed, then it would be around one percent of the fields were identified with either the disease or the pathogen.”

Since the survey started in 2008, visible clubroot symptoms have been confirmed in 82 commercial fields, while the clubroot pathogen has been detected through DNA-based testing in 42 fields.

In Alberta, clubroot was diagnosed in 5,323 canola crops in the province from 2005 to 2022, in at least 3,894 individual fields, according to the Canola Council of Canada website.

“But also Manitoba, if you look at their map, you’ll see that they have relatively higher amount of clubroot overall,” Akhavan said.

“We (Saskatchewan) still have a big chunk of the province without any evidence of clubroot disease being observed. A rough calculation, the last time I looked at the map there was 70 to 80 percent of the province still has no history of clubroot galls being observed.”

Four RMs were added this year to Saskatchewan’s clubroot map. In RM 437 (North Battleford) visible symptoms were discovered, while clubroot DNA was found in RM 339 (Leroy), RM 368 (Spalding) and RM 368 (Beaver River).

Specific land locations are kept confidential to protect producers’ privacy. Most clubroot reported is in the region from Saskatoon toward the northwest.

When clubroot started to spread in Alberta, farmers didn’t have the tools or information that is available today.

“At the time there were no resistance cultivars available, and also not much knowledge in terms of other management practices, which can be useful,” said Akhavan.

“But Saskatchewan had this opportunity to incorporate growing resistant canola cultivars much earlier. So perhaps this is one of the reasons (for relatively slow spread in Saskatchewan).

“We have no cases of resistance being overcome in a commercial field (in) Saskatchewan, while many fields in Alberta have the first generation of resistance overcome already.”

He said the slow spread is a testament that initiatives taken by grower groups, academics and producers have worked.

Akhavan said rotations with at least a two-year break between canola crops, using resistant varieties and sanitation practices help reduce the spread and establishment of clubroot.