Scientists are not able to predict which will come, but Western Canada’s hail alley could see improvement

An area in Alberta known as hail alley could potentially experience larger hail but fewer hailstorms due to climate change, said a scientist whose team discovered the biggest hailstone ever found in Canada.

“It’s tricky, right? I mean, we still don’t understand everything that’s happening now,” said Julian Brimelow, executive director of the Northern Hail Project at Western University in London, Ont. “So, to make projections about the future, you’ve got to be cautious in what you say and not jump to conclusions based on some model runs.”

Read Also

Canada the sole G7 nation without a Domestic Sugar Policy to aid local sugar beet production

Canadian sugar beet industry vastly different to US with free-market system compared to protective government-regulated sugar program

Storms with large amounts of smaller hail are more destructive for crops than events with large hail, he said.

“And we’re not yet, unfortunately, at a point where we can tease out which one’s going to prevail in the future, so that’s where we have some work to do.”

Hail alley is an area of Alberta that roughly extends from Drayton Valley near Edmonton south to High River near Calgary, as well as west past Highway 2, said Brimelow. It has been noted for having a higher frequency of active hailstorms than other parts of the province, he said.

Moisture from the growth of crops is pulled up into the atmosphere against the barrier formed by the nearby Rocky Mountains, where it meets a downward flow of dry air moving west over the foothills, he said.

The jet stream is also typically located in the region during July, joining factors such as the area’s height above sea level, he said. Calgary has an elevation of more than 1,000 metres.

It means hailstones don’t have as far to fall, reducing the risk they’ll melt before they hit the ground, said Brimelow.

“And all those ingredients together create an ideal recipe for thunderstorms and hailstorms.”

However, scientists are still unable to predict hailstorms in Canada, he said. As a result, the five-year Northern Hail Project was launched this year in hail alley, with plans to expand to other parts of the country.

Scientists hope their research could benefit everything from agriculture to the solar and wind farms that are increasingly being built in places such as hail alley, said Brimelow. It could also spark improvements in building codes by boosting public awareness of the problem, he said, pointing to the use of easily damaged vinyl siding for housing.

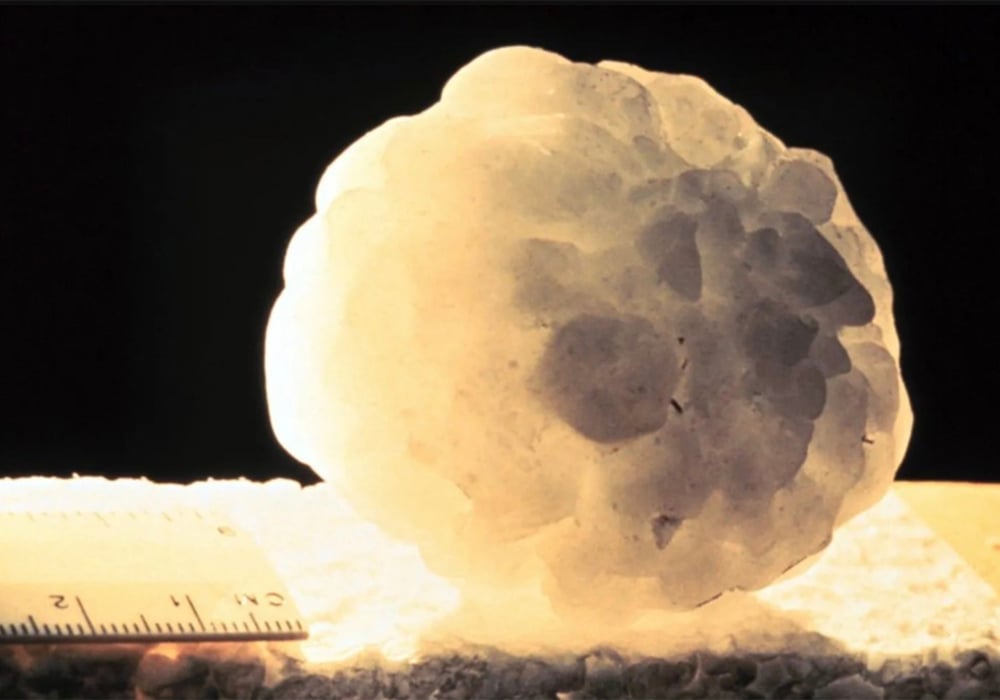

Researchers collected a hailstone Aug. 1 northwest of Innisfail, Alta., that weighed 292.71 grams and was slightly larger than a DVD disc. The discovery near Markerville broke a nearly 50-year-old record of 290 grams set in 1973 in Cedoux, Sask.

The Alberta hailstone was one of only 22 around the world that have been found to be larger than 290 grams. It was part of a hailstorm Aug. 1 that damaged up to 70 vehicles on Highway 2 near Antler Hill north of Innisfail.

Hail as large as baseballs brought traffic to a halt on one of Alberta’s busiest roads. The storm levelled crops and damaged farmhouses in Red Deer County.

However, larger stones tend to be lower in number and spread farther apart, “so they will obviously cause a lot of damage to your vehicle if they hit your vehicle,” said Brimelow. “But for a crop, it’s usually not too much of a big deal.”

He said an exception was a hailstorm in 2018 that covered the ground in a deep layer of hail the size of golf balls or larger. It caused an estimated $1.3 billion in insurable damages, affecting at least 70,000 vehicles and homes in northeast Calgary as well as destroying crops.

“That’s the probably the worst scenario for anything, especially when there’s strong winds,” said Brimelow. “So, that’s where we still need to make inroads is instead of just saying ‘hey we’re going to get hail,’ to get a more nuanced prediction of what we think is the most likely outcome on a given day.”

Although people were worried about severe thunderstorms Aug. 1, 2022, “to be honest, nobody, not even the experts, were thinking ‘today could be a record hailstorm day,’ and that’s something we need to get better at.”

This year’s hail season was within the 10-year average in terms of Alberta crop damage claims, said George Kueber, provincial adjusting manager for the Agriculture Financial Services Corp.

He estimated there had been about 7,000 claims this year, down from a peak of about 12,000 in 2012. However, he said 2022 may not have felt like an average year because hail was widespread across the province “from the far reaches of the north and the Peace district right down to the American border – from the foothills right over to the Saskatchewan side as well.”

Some clients in the Peace district told Kueber they hadn’t had a hailstorm since 1962. As a result, he expected the total cost of this year’s claims in Alberta will be higher than the seven- to eight-year average of about $300 million.

Despite such totals, dry weather in much of the province this summer helped suppress hailstorms toward the end of the season, said Kueber.

“Like I said, once we kind of got into August, the hailstorm activity slowed down drastically.”

Brimelow said research to better understand hailstorms has tended to be overshadowed by losses to life and property caused by tornadoes.

“But now, since about the early 2000s, that tide has been turning as hailstorms become more problematic not only here in North America, but in Europe and in Australia, too, and elsewhere.”

Although the increasing hail damage is partly due to the growing global population of people around the world, creating more targets over a bigger area, “if you account for that, it still looks like we might be seeing a signal that we’re getting more severe hail events,” he said.

“On the other side of the coin, some areas like the southeastern U.S. are probably going to see fewer hail days because hail there tends to be smaller, and with warming (due to climate change), your melting level increases in height. And that means the hailstone is going to have a longer time below the melting level and is probably going to melt before it gets to the surface.”

Much of the rain from thunderstorms that Albertans experience in hail alley was probably small-sized hail at some point as it travelled within the cloud, said Brimelow.

“And it does look like hail alley is one of those areas in North America where there are strong suggestions that is what we could be seeing: maybe fewer days in the future, but those days when it does hail, it looks like the chances of all the ingredients coming together to produce large hail are going to be in place.”