Imagine a world with fewer cars, more trains and systems that looked like something out of a sci-fi movie, such as hyperloops, transporting people throughout the country.

The idea might seem farfetched, but for some they would address key challenges facing rural and urban communities, making them more sustainable.

“The possibilities and potential are there,” said Thomas Fryer, the founder of Alberta Regional Rail, an advocacy group that’s spreading awareness about what it says are the benefits of a rail network in the province.

Read Also

New coal mine proposal met with old concerns

A smaller version of the previously rejected Grassy Mountain coal mine project in Crowsnest Pass is back on the table, and the Livingstone Landowners Group continues to voice concerns about the environmental risks.

“It’s not just economic potential, but there is environmental and social potential,” Fryer said.

The issue of offering better rural transit came to the forefront last year when Greyhound shuttered Canadian operations. Before that, the Saskatchewan Transit Company came to a halt.

The decisions sent shockwaves to users who used the service, and left transportation gaps in many places that have yet to be filled.

Since then, rural advocates, environmentalists, urban planners and some economists have been pushing for better rural transportation that doesn’t involve cars.

Many say it would allow small communities to remain viable, given members wouldn’t have to move to urban centres to access health care and other services.

It would mean less emissions because there would be fewer vehicles on the road. As well, people could spend more time with their families or on work rather than waste hours sitting in traffic.

For instance, congestion cost US$305 billion in economic losses in the United States in 2017, according to transportation consulting firm INRIX.

INRIX didn’t calculate economic losses in Canada, but drivers in Toronto and Montreal have lost on average 164 and 145 hours to congestion, respectively. Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg and Saskatoon lost 88, 89, 94 and 42 hours to congestion, respectively.

“Catching a train, for example, would be less stressful,” said Fryer, who’s also a project engineer and construction manager with an oil and gas company.

“There would be health, environmental and social impacts, but they are unquantifiable.”

The problem, Fryer said, is there is a lack of will to get governments, the public and corporations on board. It would require an overhaul of how people in North America go about their lives.

“People don’t understand what is available and what could be done,” he said.

He pointed to Europe as a country with a robust rail network. Technology in developing rail cars and locomotives is more advanced there, he said. They are light, fast, efficient and low in horsepower, largely built for transporting people.

In North America, he said, rail cars and locomotives have been developed to primarily accommodate freight. They are heavy and require lots of horsepower.

He said Europe’s technology can be implemented here, but it’s up to companies and governments if they want to bring it over to North America.

His main objective with Alberta Regional Rail is to show what’s achievable. He doesn’t want another lane built on Highway 2, the main corridor between Edmonton and Calgary.

“I think there is a better way than to be forced to drive between Calgary and Edmonton,” he said. “How many people are going to get injured and die on that highway this winter? How much could be prevented if there was a rail connection, instead?”

Despite aspirations, the costs of building and operating infrastructure would be high.

A recent study that looked into transit between Calgary and Banff National Park found a year-round train would cost roughly C$660 million to $680 million to build and about $13.4 to $14.3 million to operate.

All-year busing would be cheaper, with capital costs ranging from $8.1 million to $19.6 million. Operating costs would be between $4.5 million and $5.8 million.

Fryer, based on his own calculations, estimated a new rail line between downtown Calgary and Edmonton would cost $1.5 billion.

“We can calculate the cost of developing and operating rail, but it’s the benefits that are unquantifiable,” he said.

Despite the high price-tag, Fryer points out rail has a long history in Canada and could be used once again.

He has developed his own map of an ideal network that would connect much of Alberta. It would include existing Canadian National and Canadian Pacific lines that were once used for carrying passengers decades ago.

According to the Forth Junction Heritage Society, an Alberta-based group that preserves and shares the province’s transportation history, Alberta once had an extensive network of passenger trains.

The Calgary and Edmonton line operated for 94 years until it closed in 1985. Financial losses and collisions led to its demise.

As well, during that time, governments invested heavily in freeway systems across the U.S. and Canada. Automobile-use surged, providing commuters with an alternative. Cars were marketed as liberating and they eventually became the family ideal.

“It was promoted that the car gives you more freedom,” Fryer said. “Car ownership and driving was pushed more.”

On top of that, North America has large oil reserves, which ensures easy access to gasoline at a relatively cheap price.

Most of Europe is heavily reliant on outside countries for oil, meaning much of the continent had to develop alternative energy sources and be more efficient with transporting people.

But are railways the right approach?

The market in North America has so far shown little appetite to connect vast distances by rail.

CP Rail has not indicated it wants to get into passenger rail service. CN has said it has no plans for passenger transportation, but it is collaborating with Via rail, a federal crown corporation, and other providers to use its tracks.

Via Rail has one line that goes from Vancouver to Toronto. There are also relatively shorter lines in the greater Toronto and Montreal areas, as well as one to the Maritimes.

What the market has so far spurred, however, is bus services.

Since Greyhound closed, Saskatchewan-based Rider Express has stepped in to cover major routes between large western Canadian centres. Other companies have also filled some areas.

Firat Uray, owner of Rider Express, said the company has been successful financially.

However, service gaps remain, especially in many rural communities that aren’t on Highway 16 and Highway 11, which connects Regina, Saskatoon and Prince Albert.

Uray said the company won’t be able to reach those people unless the government offered funding.

“I think in the future there will be a bus service between bigger centres, but not bus service to smaller places unless the government steps in,” he said. “It’s not sustainable to operate in all rural areas.”

The federal government has said it would cost-share with provinces on intercity bus services to fill gaps left behind by Greyhound, according to a statement from the Ministry of Transportation.

It said it has provided $10 million in transitional funding for this initiative. The funds are available until 2021 and British Columbia so far is the only province that has accepted supports.

Canada is also looking to address long-term solutions by working with provinces to address people’s mobility needs.

As well, rural transit pilot projects are currently underway in Alberta. Many seem to be going well, but it’s uncertain if they will last if government funding doesn’t continue.

As for rail service, it only works well when lines are shorter and connect to major centres, Fryer said.

“Up to 150 kilometres you are looking at regional rail, and then up to 400 km, you’re looking at high-speed rail,” he said. “Beyond that, air is more efficient.”

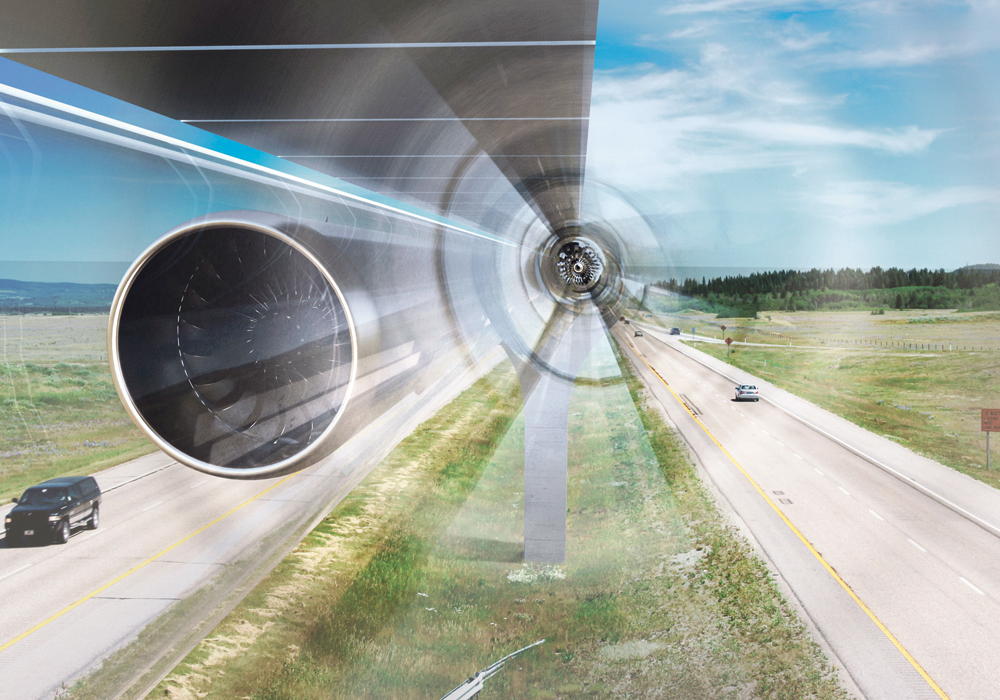

There are proposals for what’s called a hyperloop in Alberta. It’s essentially an extremely fast and futuristic monorail that transports passengers and goods in an enclosed vacuum tube. Again, the hyperloop would connect major centres, rather than far-flung communities.

So, where does this leave small communities that aren’t on a line?

Some suggest bus services, car shares or other less intensive modes might be able to fill that gap, funneling people to centres along the main route.

However, that will take immense co-ordination between municipalities, organizations and companies for that to work.

Co-ordination is just one solution to the problem, according to the Transit Co-operative Research Program report. But when it does work, the report said it will eventually allow for the creation of a transportation system that serves more people at a lower cost.