Optical colour sorters have been employed in the delicate task of kicking bad seeds out of high-value pulse crops for about two decades. But now they do so much more.

“The technology has really advanced in the past five years. They’re bigger and they handle more volume faster than before. The hardware and software are more sophisticated, enabling them to perform a wide variety of tasks, and with greater accuracy. The capabilities are far greater than previous sorters,” says Mark Metcalfe, president of Nexeed in Winnipeg.

Read Also

New program aims to support plant-based exports to Asia

Understanding the preferences of consumers in Taiwan and how they differ from Indonesia or Malaysia isn’t easy for a small company in Saskatchewan.

“The new sorters have more processing capacity and camera resolution. There are more cameras that can be added, so now we’re well beyond the visible spectrum of light. Our sorters can detect defects on a seed with wave lengths that we cannot see with our eyes, such the removal of seeds affected by sclerotium.”

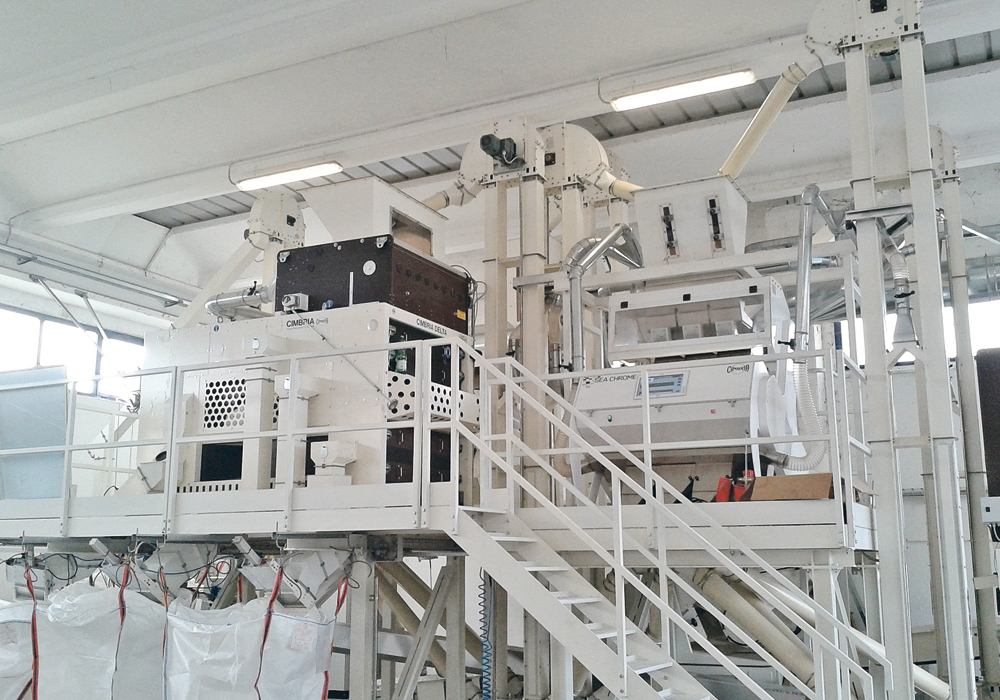

Nexeed is the Canadian importer of Danish-built Cimbria sorters, considered to be world leaders in optical sorting technology.

Metcalfe said the top-of-the-line Cimbria SEA Chromex can discern 16 families of defects in a seed. The camera is full-colour RGB with 4,096 pixels. The camera scans 18,000 times per second and recognizes 16 million distinct colours. It has optical resolution down to 0.06 millimetres.

The unit can carry 200 sorting recipes on-board at a time. This degree of precision allows a seed plant to produce a high-quality lot of pure seed that meets the most demanding criteria of buyers.

The Chromex has a list price of $450,000. At the lower end of the scale, an entry level optical sorter sells for about $110,000.

“This high level of accuracy and volume we now have in seed sorters has been standard in the food processing industry for decades. It’s only recently been applied to seeds and crops.”

He said that when a seed grower does a makeover of his plant, an optical sorter is nearly always an automatic addition. Sorters are also added when a certain crop problem shows up in a certain region, such as deoxynivalenol (DON) in cereals. Once the seed grower sees how many operations the sorter can handle, he puts it to use for all kinds of cleaning challenges.

“One simple example is we have seed growers adding an optical sorter if they have an ongoing problem, such as wild oats,” he said.

“They’ve always been able to cope using mechanical sorters, but it’s difficult because the two seeds are about the same density and size. However, the wild oat is darker, so the sorter sees the difference between the wild oat seed and the tame oat seed and kicks the wild seed out with a blast of air.”

Metcalfe said fusarium and weeds and volunteers are other examples, and optical sorters can be part of a long-term solution to both problems.

“When it comes to fusarium, the technology we have today does a pretty good job of identifying and removing damaged kernels., and Cimbria is continuing to develop better fusarium detection technology,” he said.

“Saskatchewan farmers had high DON content in durum a couple years ago. DON kernels aren’t like fusarium damaged kernels, which you can see. We cannot yet visually identify and remove DON kernels in durum.”

Metcalfe said DON detection results using optical sorters were inconsistent. Sometimes plant operators got good results but the next batch wouldn’t catch the DON kernels. He said Cimbria is working to come up with the necessary algorithms for detecting DON before conditions for the disease return.

“I believe it’s inevitable that DON conditions will return, and we’ll some day have to face new weed and disease problems,” he said.

“What new problem is waiting to explode in the future? There could be issues that are minor right now, or confined to a small area, that will wait for the right conditions to explode.”

Metcalfe said that although farmers are interested in optical sorters, the fact is it takes a pretty hefty volume of seed to justify the investment, especially if there’s no existing facility to house a sorter, feed it and remove the good grain and the rejects.

He said it’s more feasible if there’s space in an existing on-farm plant. He reminds producers that there’s all the other equipment and infrastructure that surrounds an optical sorter, even in a small plant. They will still need their regular cleaning equipment.

“A complete optical sorter set-up from scratch, going from not having one to having one, can cost $350,000 to $500,000,” he said.

“Most of our new customers for optical sorters are in the seed business, but lately we’ve been seeing farmers buying sorters and use them in processing value-added products on the farm. And I think that market will continue to grow as more farmers look at adding value before a commodity leaves the gate.

“The other big thing is companion cropping. If you have two cash crops mixed together, an optical sorter will be the best way to create two bins of distinctly different seeds.

“This group includes organic growers. They naturally have more weed and foreign material in their grains and end users don’t like that. A cleaner product attracts a higher price. Growers with IP contracts are also beginning to see the value in having a colour sorter. The industry not only documents the history of the product, but they also emphasize quality, and quality is what you deliver to the end user by removing defective kernels.”

Metcalfe said an enterprising farmer can do a wide variety of things with a sorter. With 200 sorting recipes loaded into the machine at any given time, the operator can be cleaning up organic flax first thing in the morning, remove ergot from wheat later in the morning and then set it up for removing kochia from lentils in the afternoon. It should not be hard to attract local farmers who want custom seed cleaning done.

The basic sorter covers all the light waves seen with the human eye. A buyer wanting to get into non-visible defective seeds can buy the optional infrared cameras appropriate to crops and conditions in his area. Programs are also available to identify defects in size and shape.

“If a person ordered all the optional technologies, they would have a machine capable of identifying virtually anything that could be colour sorted. The basic seed sorting machine with a red-green-blue camera can sort anything that is needed for an organic or identity preserved application.

“All the basic algorithms for different crops and combinations have been developed and tested, but we always do fine tuning on each machine on site,” he said.

“And we teach the operator how to tweak for better performance because crop conditions change from year to year. Part of what we do is teach operators how to set up their own new recipe so they can do new combinations that don’t come already installed.”

The smallest Cimbria sells for $110,000, but Metcalfe said the entry level machine handles only about 150 bushels per hour, so it has a limited appeal.

The next logical step up carries a price tag of $150,000 and handles about 450 bu. per hour. He said this sorter can run enough seed to make it a viable purchase. H

The biggest Cimbria optical sorters handle up to 1,000 bu. per hour, he added.

“Customers tell us they bought the colour sorter for one certain purpose, but once they had it they figured out all kinds of other jobs for it,” he said.

“For one thing, it takes some of the burden off the other cleaning equipment. They increase the performance of the whole plant by 10 percent or more.”