WINNIPEG — Jay Whetter and I sat before the ancient portal, like Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon did 102 years before at the mouth of an Egyptian tomb.

“I wonder what’s on it. Do you have a sense of what it could be?” I’d like Whetter to have said that at that moment of revelation.

“Yes, wonderful things!” I wish I’d replied.

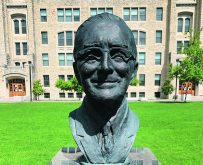

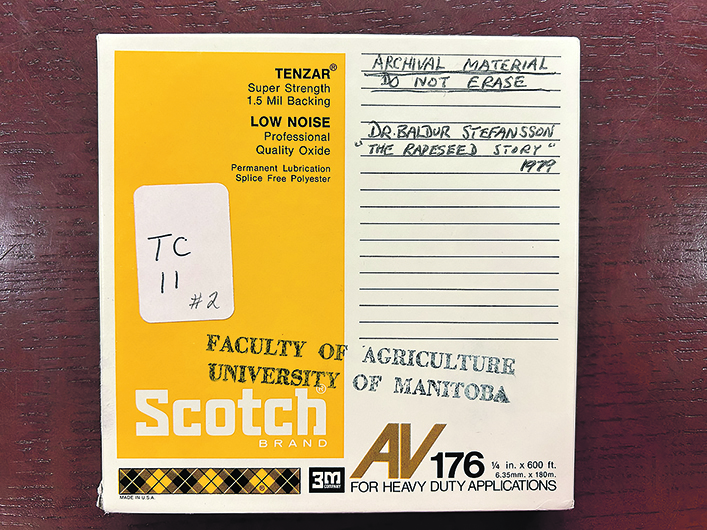

Sure enough, as the digitized reel played, we intrepid canola history archaeologists were the first contemporary journalists to hear the words spoken by the voice of Baldur Stefansson telling The Rapeseed Story.

It wasn’t solid gold treasure from 3,300 years ago, but to agricultural journalists, this was golden. Few men have stood at the gates of a heroic era to report upon what led up to it, as Polybius did with the peak of the Roman republic. Fewer have been responsible for creating that era.

Baldur Stefansson, in this recording, was both.

In the seven minutes of salvaged reel-to-reel tape from 1979, Stefansson tells a much-abridged true story of the creation of canola, a global commodity, healthy food superstar and Canadian triumph, in his stilted voice and intonations.

Remember those years when radio hosts, anchormen, sportscasters, authors and intellectuals on TV and radio spoke in an imposing, voice-of-God way? You know, the form of speaking exemplified by Lorne Greene?

You knew those guys didn’t really talk like that when they were off mic/camera, but the voice of authority was definitely employed when speaking about Important Matters.

Well, Stefansson has got that in spades in this recording. Here was a Voice of God relating how he took humble clay and breathed life into it. Yet, when hearing this voice, one finds no ego, no vanity, no self-regard behind it. It’s just God telling you how he created. In a way, it’s very humble.

It also carries the sort of formal tone we found in rural luminaries some decades past. Plus, a bit of an Icelandic accent.

OK, I wouldn’t have caught the Icelandic bit if I hadn’t been wading through Stefansson’s archives at the University of Manitoba, in which collected reports on his pioneering canola work were reported with far more breathlessness than in mainstream Canadian publications, and in which his numerous awards from Canadian-Icelandic and Iceland-Icelandic organizations are documented. But I’d like to believe I can catch that tinge to his tone.

In many ways the recording is a glimpse into a world that no longer exists.

“Some visitors to our country have asked, what is this yellow stuff you grow here?” Stefansson says at the start, which has been preserved on a dodgy reel-to-reel tape in the Stefansson boxes in the U of M archives.

“They appear to be surprised to learn that most of these fields are rapeseed.”

Well, there’s a lot to unpack there, historically.

This was before rapeseed was fundamentally changed, in which the semi-indigestible erucic acid and high glucosinolates that made the crop a crappy choice for both human health and animal feed were bred out. The result was renamed “canola” to recognize the transformation and avoid confusion. (The Europeans are still confused by this.)

Today, nobody interested in crops would fail to know what canola is. It’s the dominant crop in Canada and important in Australian, Kazakh, Indian and Chinese farmers’ rotations. In terms of acreage, it’s probably on more farmland than the millions of farmers in the Roman Empire tilled.

There’s much else different about the world from which Stefansson is speaking. Imagine saying this:

“Apparently it will be possible to produce rapeseed oil which will in some ways be better than soybean oil.”

After decades in which canola oil has been generally accepted as being much healthier than soybean oil, not many people consider it exciting to ponder the possibility that it might. It’s just a given.

This was also a world in which most commercial variety development came out of university and government research programs, rather than today’s commercial lead on in-field varieties and the public sector’s focus on early, foundational research.

“We at the University of Manitoba were the first in the world to show that it was possible to make this change in rapeseed oil by changing the genetic or inherited characteristics of the plant,” Stefansson says proudly.

He then notes that Tower, the first of the modern canola varieties with low erucic acid and low glucosinolates, came out of Saskatoon.

While much has changed since this 1979 recording, some things are the same. And some have alarmingly reverted to their status in the late 1970s, when an awful inflationary spike ravaged family incomes and made millions of Canadians poorer.

“We have all witnessed the drastic increases in price which occurred in sugar and coffee,” Stefansson says. “I believe the existence of an efficient edible oil industry in Canada has helped and will continue to help to prevent such a drastic increase in prices in our margarine, shortening and salad oil.”

Indeed. At the end of the day, creating canola was about creating a vital human and animal food, something nobody should ever take for granted.

The recording is only seven minutes long. I’d been waiting months to hear it, after the University of Manitoba offered to get the fragile reel-to-reel tape sent to a digital restorer and make it available if it was possible. Jay Whetter, a longtime agricultural journalist, contacted me about the tape and asked if he could listen to it.

I thought it would be good if we listened together, as probably the first journalists to hear it in ages, so at Manitoba Ag Days we broke through that door and heard the words of 1979 Stefansson telling The Rapeseed Story.

There are no secrets here, no priceless artifacts, but the gold is in experiencing the honest expression and excitement of a man standing at the beginning of a revolution he helped create, one we still live with, to our great benefit.