NOW:

It might be hard for farmers who have been coping with flooding for the past few years to imagine dealing with drought, but that day is coming.

Scientists just can’t say exactly when.

Drought has been a major threat since agricultural production began on the Prairies.

The region is typically dry and often affected by regional drought, but it has seen major widespread droughts, particularly in 1931, 1961, 1988, 2001 and 2002.

David Sauchyn, a geographer and senior researcher at the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative in Regina, said the best guess is that the next major drought will occur late in the next decade.

Read Also

VIDEO: Agritechnica Day 4: Robots and more robots, Nexat loves Canada and the trouble with tariffs

Agritechnica Day 4: Robots and more robots, Nexat loves Canada and the trouble with tariffs.

The wild card is climate change.

Research has already identified wet and dry cycles since long before people decided to farm the Prairies.

Sauchyn and others have examined about 8,000 tree ring samples that clearly show those periods.

“We’ve got a pretty clear idea of what the cycles have been for the last 1,000 years, so if we just project into the future, then that’s what it suggests,” Sauchyn said.

“But extrapolation is a pretty nasty game because it’s happening in a changing climate.”

The wet and dry cycles have tended to run in 15-year periods, which Sauchyn said means the region is due for a minor drought within a couple of years.

“We’re probably not going to get a devastating drought for a few years,” he said.

The period after the 1930s until about the mid-1970s was characterized by wet and dry periods. The driest times tended to be individual years, such as 1961.

However, there were more dry years after the mid-1970s.

“We get these fairly long periods of about 25, 30 years in which drought is pretty common and then it’s not very common at all,” Sauchyn said.

“About 10 years ago we entered into a period in which drought probably isn’t going to be that common for a while, but that doesn’t prevent us from having a really dry season or even a dry year, but two or three or four dry years in a row? Probably not for a while.”

The difficulty with predicting what will happen on the Prairies is the natural variability in the system. It isn’t uncommon for temperatures to swing by 15 degrees or more within days. For that reason, the region will be among the last to notice the effects of climate change.

Sauchyn said places where climate is constant easily notice a one degree change. “Here, a one degree change is hilarious,” he said.

So, even though people know the climate is changing — yes, warming overall — and the consequences will include drought and a lack of water, it’s hard for people to separate that idea from the natural variability that has always occurred.

Those who lived through significant drought know how bad it can be. The fear now is a drought that lasts longer than one or two years in a warming climate.

“What if we get a 20-year drought like the 1850s and 1860s … or the 1790s, or the 1720s,” Sauchyn said.

“We know these droughts pretty well now because we’ve been collecting lots of information about them from trees and from historical documents.

“They were much worse than the 1980s, the 1930s. And it’s bound to reoccur, and when it does it’s going to be in a climate that’s much warmer than 200 years ago or 300 years ago.”

Sauchyn is currently mid-way through a five-year drought project that includes study areas in southwestern Saskatchewan, southeastern Alberta and several South American countries.

The research included stationing graduate students in small communities within the areas to talk to producers about their experiences. Four students conducted 170 interviews in and around Rush Lake and Shaunavon in Saskatchewan and Taber and Pincher Creek in Alberta.

The scientific research will be combined with the stories on the ground to help prepare for the future.

“If the science says (a) 10-year drought (is coming), that will take a lot of adaptation of government programs and policies,” Sauchyn said.

“That’s beyond the capacity of individual producers.”

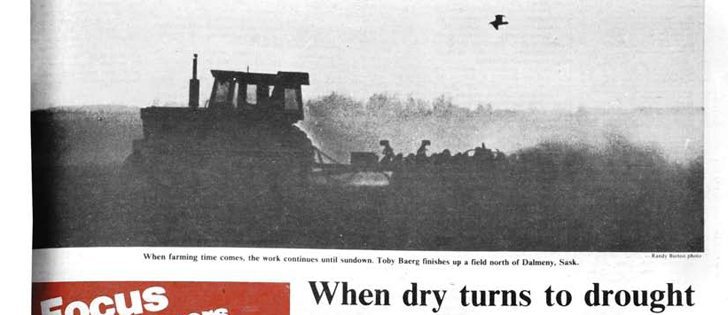

THEN: When Dry turns to drought

If there is no rain by the end of May, the long-feared Prairie-wide drought will be a reality.

Agricultural observers from the three Prairie provinces say the dry conditions caused by nine months of below-average precipitation will create a “crisis” on pasture and seeded land if clear skies persist until the end of the month.

Homer Frederickson, supervisor of Saskatchewan’s community pastures, says the provincial government is delaying the spring filling of the numerous community pastures as long as possible in hopes of early rains.

He says the growth on the provincial pastures has been slow but, so far, the drinking water hasn’t been affected. Even if rain doesn’t come, the pastures will be opened soon but without moisture it is doubtful they will support many cattle for long. “We will continue to operate as normally as we can for as long as we can but if we don’t get rain that might not be very long.”

Frederickson said the community pastures will be filled to capacity and cattle will be held “to the absolute end” in hopes of saving farmers’ pasture for the latter part of the summer.

Gary Jones, a cattleman in the Crane Valley, Sask. area, southwest of Regina, said his area and the southeast area of Alberta are about two weeks away from forgetting about an average hay crop if rain doesn’t come.

Download a PDF of the original WP page here: 1980_may22_p01