New demands for ammonia, unpredictable production and the war in Ukraine form a loose foundation under the market

REGINA — Global fertilizer demand is growing, even as supplies dwindle due to production issues and other limitations.

High natural gas prices used to produce nitrogen fertilizer are a leading problem, but that is not all.

The nitrogen fertilizer issues from 2022 will be visited upon 2023, but will not be as extreme as they were through spring and summer, when European natural gas prices peaked in the area of US$90 to $100 per million British thermal units in August.

Russian gas supplies came under restrictions as the war in Ukraine worsened when Nordstream One and Two explosions further curtailed deliveries.

That price appears to have stabilized at about $40 per million b.t.u. and may remain in that area well into 2022, say analysts, and futures prices seem to confirm this.

Put into perspective, the current $40 equates to about a C$1,250 to $1,400 per tonne urea in Western Canada.

Global prices for natural gas have been high enough to cause European plant shutdowns, further shorting supplies.

“The EU accounts for about 10 percent of global nitrogen fertilizer production and through the third quarter of this year about half of that has been shut down,” said Jason Newton, the chief economist for Nutrien and head of market research for the company, speaking in Regina last week at the Grain Expo event held during Canadian Western Agribition, which ran Nov. 28 to Dec. 3.

While ammonium nitrate is still profitable there, production overall remains impaired by gas prices, he said.

As a result, the EU is importing large quantities of nitrogen fertilizer.

“North America is generally a net importer of urea. However, that has changed as well. High prices in Europe and a relatively discounted price in North America have seen imports fall significantly and actually quite a large volume of exports from the (United States) Gulf Coast that have the flexibility of exporting when the price is right,” he said.

Tyler Freeman, who analyzes fertilizer markets for Parrish and Heimbecker, said supplies from the Gulf Coast are tight.

“We have seen, despite challenges on the river (with low water levels), record imports of urea this year… but capacity is getting pushed to the max, hard to get new supplies off the river,” he said.

In 2023, the import-export balance will have to shift to meet needs for the coming crop and that means North American prices must become competitive with those available overseas.

Russian ammonia isn’t usually used as fertilizer. Instead, it ends up in other industrial uses, which means those buyers are competing for supplies that were once used in urea.

Much of it traditionally flows through a pipeline across Ukraine to the port of Odessa. That is shut down and Russia has few options for exporting.

Reductions in Russian ammonia exports through the Black Sea and restricted Chinese urea exports are combining to create shortages in the international market. Russia is a leader in the industry and its exports fell from a little more than four million tonnes to an estimated one million, according to commodity analysts CRU, Argus Media and Nutrien.

China, a large consumer and producer of nitrogen fertilizers, is blocking exports of urea in an effort to control farm costs and keep food prices low domestically. That keeps traders from arbitraging domestic and worldwide prices.

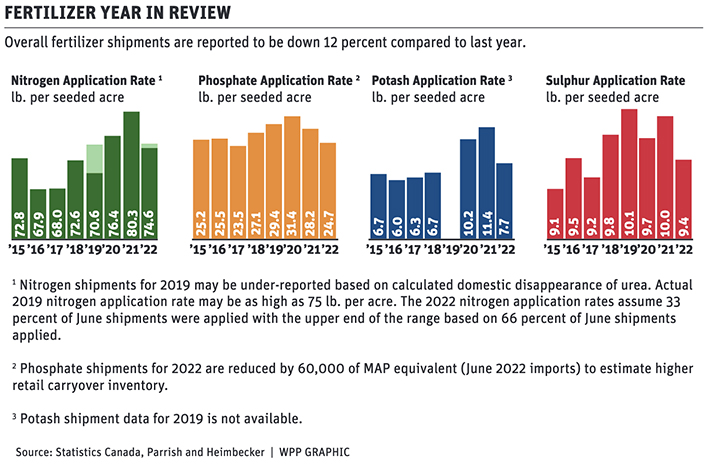

Higher prices have had an effect on how Canadian producers are using fertilizers, including nitrogen. Freeman told Grain Expo attendees that farmers in Canada pulled back on their applications by about 12 percent, based on Statistics Canada numbers, as a form of risk management and considering the 2021 drought carry-overs in the fields.

“More soil testing, better tools and after putting on record rates in 2021 and significant carry-over from a droughty year, this shows farmers here are using fertilizer responsibly and that should be a message to policy makers,” he said.

“The 80 pounds (of nitrogen fertilizer applied in 2021) didn’t do the job they hoped. We heard there were farmers top-dressing nitrogen well into June and a few weeks later regretted it as it didn’t rain. So, when it comes to this spring, we are likely back to 2018 and 2019 kinds of numbers,” said Freeman.

“For this current year, the market is hugely volatile. It is very hard to come up with numbers to make any purchase recommendations on,” he said.

“You saw days when natural gas prices moved in that day more than the total price of natural gas in Alberta. That is the kind of risk fertilizer producers in Europe are working in and we feel it here,” he said.

Newton said Chinese domestic policy comes into play as that country is an important swing producer and exporter and it is unpredictable.

Freeman said: “The market is quite nervous and is trading on headlines and emotions right now.”

On the supply side he said the world could use three world-class production facilities being built annually to meet all the new demand for ammonia from fertilizer and growing energy use for hydrogen-based transportation.

The challenge for retailers is all of the volatility in the marketplace, said both analysts.

Freeman suggested that in many cases the seller’s margins on urea can be a lot less than the potential short-term shifts in price.

“If you can make it work in your farm’s plan for cash flow and margins, you might want to lock that up,” he said.

He suggested there are currently some urea tonnes available in Western Canada at or below $1,000 and if producers can take direct truckloads to their farms, prices are pretty attractive, relatively speaking.

“The good news is that on a per-acre basis the difference between timing your (nitrogen) price right and missing it might only cost you $5 to $10 (per acre). And there are strong margins out there to support it,” said Freeman.