LANGHAM, Sask. — The session at the Ag in Motion farm show near Saskatoon was titled “Uncover the secrets below your soil’s surface.”

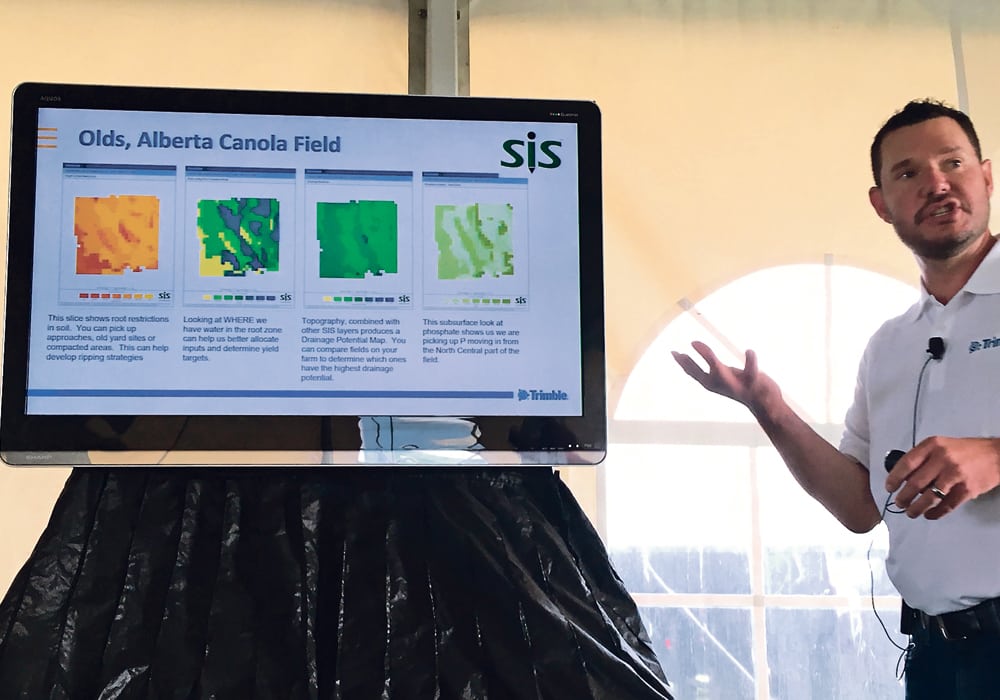

Mark Kuehn, project manager with Trimble’s Ag Business Solutions sector, was tasked with explaining how that can be done and how Trimble has done it for various clients.

The company uses a Soil Information System (SIS) to get soil and topographic information that can be converted to three-dimensional maps. Though other companies do similar work, Kuehn said this system can measure up to 75 different soil properties ranging from texture, compaction and moisture to macronutrients, micronutrients and topography.

Read Also

Crop quality looks good this year across Prairies

Crop quality looks real good this year, with the exception of durum.

Rates vary with the type of service selected but Kuehn said it’s about $40 per acre for broad acre use on crops such as canola and wheat.

“With the different data layers that we have, and being a multi-year investment … you’re investing in the farm,” Kuehn said.

“It’s not a one-year thing that you’re going to have to pay $30 or $40 each year. You’re going to have that data to mine for different types of information — one year looking at amending the field for soil pH levels. The next year you might be looking at fertility. Another year you might be looking at compaction on the field and then wanting to do some tillage to take care of that compaction.”

The unique aspects of SIS include soil analysis up to 1.2 metres deep with resolution up to two metres. It also includes proprietary data extrapolation to create soil property maps.

It starts with mapping the field using sensors mounted on a truck or all-terrain vehicle that map topography and measure electrical conductivity (EC).

“We believe that EC is a great tool but there’s a lot of different things that can influence your electromagnetic conductivity reading that you’re getting in the field, whether it’s high clay content, high soil moisture, high salt levels, compaction,” Kuehn said.

“All of those things will have an influence on the field. So it’s a great tool to see spatially the variability across the field but we believe that it’s very important to go out and actually ground truth what’s actually causing those readings in the field.”

In addition to EC readings, a probe collects physical soil information such as compaction, soil type and moisture levels.

Information from the soil probe is run through a program and based on the number of different soil groups in the field and their distribution, soil cores are taken to get fertility information, said Kuehn.

“We can map a quarter section within a day. Then that information is then sent to a lab for the soil fertility analysis. Once we get that info back from the lab, which typically takes about a week’s time to get that information back — once that data is then compiled and then uploaded to our Trimble processing servers, we can turn that data back around within one- to three-days time.

“So the total process from when we enter the field to when you have the information back is probably going to be seven- to 10-days time.”

Kuehn gave examples of how SIS has saved farmers money and labour. In one case, a farmer near Kalispell, Montana, purchased land intending to grow alfalfa. General samples revealed low pH levels that would require up to 3.5 tons of lime per acre to remediate. At about $230 per ton, full application at that rate would have cost more than $100,000, said Kuehn.

By using SIS and its more detailed soil mapping, the field was shown to have more pH variability than previously assumed. Using a variable rate map, less lime was applied and it saved the farmer about $48,000.