Residents of the Blood Reserve in southern Alta. worry about farming practices conducted on their land by non-natives

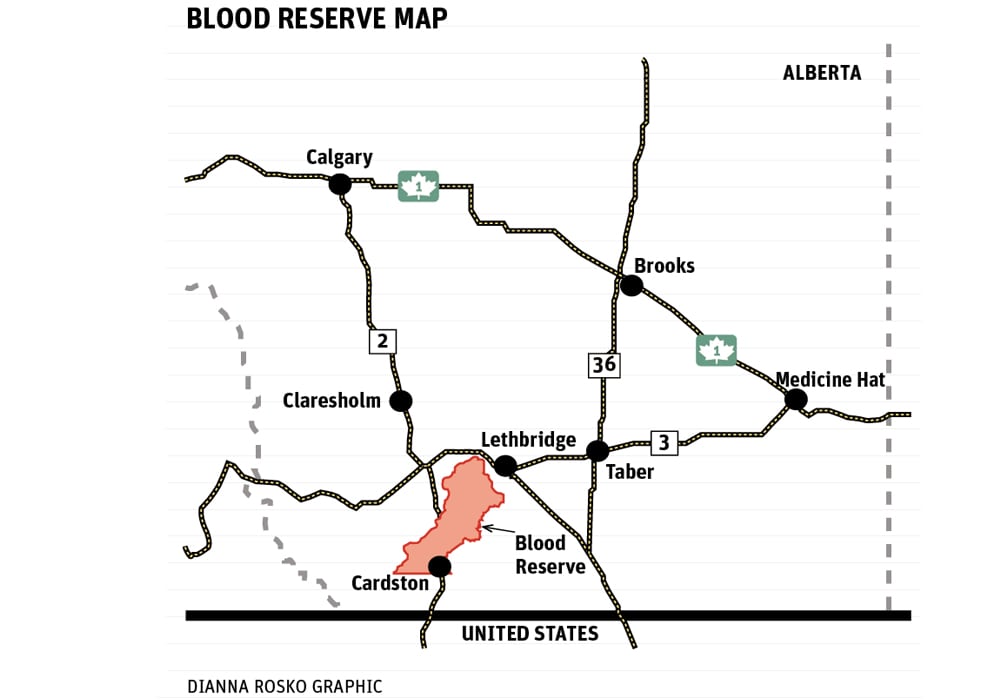

STANDOFF, Alta. — The people of the Blood Reserve hold cultural and spiritual connections to the land in Alberta’s southwest.

Some are worried that non-native farmers issued permits to farm some of the reserve’s 200,000 cultivated acres are adversely affecting the health of that land. They also fear for the future of the other approximately 150,000 acres of native grassland.

Several First Nations people voiced their views June 6 during the fifth annual summit of the Kainai Ecosystem Protection Association.

“We don’t know what’s being put in our fields,” said Beverly Hungry Wolf, a writer and member of the Blackfoot Confederacy. “We don’t know what our children are breathing. A lot of chemicals that are being on our reserve are very detrimental for our people.

Read Also

No special crop fireworks expected

farmers should not expect fireworks in the special crops market due to ample supplies.

“Our ceremonies, our way of life, our language, it all includes how to be gentle with the land, how to be gentle with the animals.”

William Singer, an artist and also a member of the confederacy, voiced concern as well, noting it is “a warrior’s duty” to take care of the land.

“We need to be more responsible in our agricultural practices,” said Singer.

Several non-native farmers have three-year permits to farm parts of the reserve and they must apply for those permits and agree to employ best management practices.

Elliott Fox, former director of the Blood Tribe Land Management Department, said the permit parameters are extensive and they address the use of herbicides and pesticides.

Fox said non-native people farm much of the land in part because tribal members don’t own property or have title to it.

“Because farming is so expensive nowadays, very few of the people that occupy the land can afford to farm it, and because they don’t have title they can’t get bank financing. It’s a real dilemma.”

Farmers who are granted permits make payment to the federal government, which then provides it to the tribal council. That council then disperses the money to reserve residents who occupy the land under permit.

Fox said presentations at the summit indicate an interest in reclaiming some cultivated land and major interest in preserving the native grassland that remains.

In fact, a moratorium has been declared on any further disturbance of native prairie on the reserve, said Kansie Fox, the environmental protection manager with the Blood Tribe Land Management Department.

However, reclaiming cultivated land would be problematic, she added.

“There’s been some talk about it but … it’s not producing any sort of income if they do that. Maybe if there was an initiative or some sort of compensation if they did do that, then that would be more of a thing.”

Kansie Fox confirmed that farmers with permits to grow crops on cultivated reserve lands must agree to follow best management practices but monitoring their activities and enforcing the rules can be an issue.

“We do yearly evaluations. We bring in the farmer and talk to them,” she said.

But real enforcement would require more monitors.

Rangeland management specialist Barry Adams told those at the summit that restoration of cultivated land to native prairie could take 25 years or more, depending on the region.

Drier grasslands are easier to reclaim but there is little data on restoration of foothills fescue, the native grass common to parts of the Blood reserve.

Harley Bastien of the Piikani reserve said the ever-growing need for food production is at odds with restoration of grasslands.

“Prairie restoration is kind of a dream,” said Bastien. “I don’t see it happening on any great scale. But the existing grasslands have to be treated like they are gold. Every one of those species has a spirit.”