Farmers know all about living with gophers, coyotes and deer, but not many have had to deal with free-ranging bison.

However, producers living near Prince Albert National Park in northern Saskatchewan have been living in the midst of a free-ranging herd for decades.

Saskatchewan’s natural resources department acquired 50 bison from Elk Island National Park near Edmonton in 1969 and released them as a food source for First Nations in the province’s Montreal Lake region.

However, the bison did not stay where they were released. The herd split up and most travelled south. Many were recaptured and relocated, but at least 10 bison settled in Prince Albert National Park and formed the nucleus of what is known today as the Sturgeon River Plains bison population.

Read Also

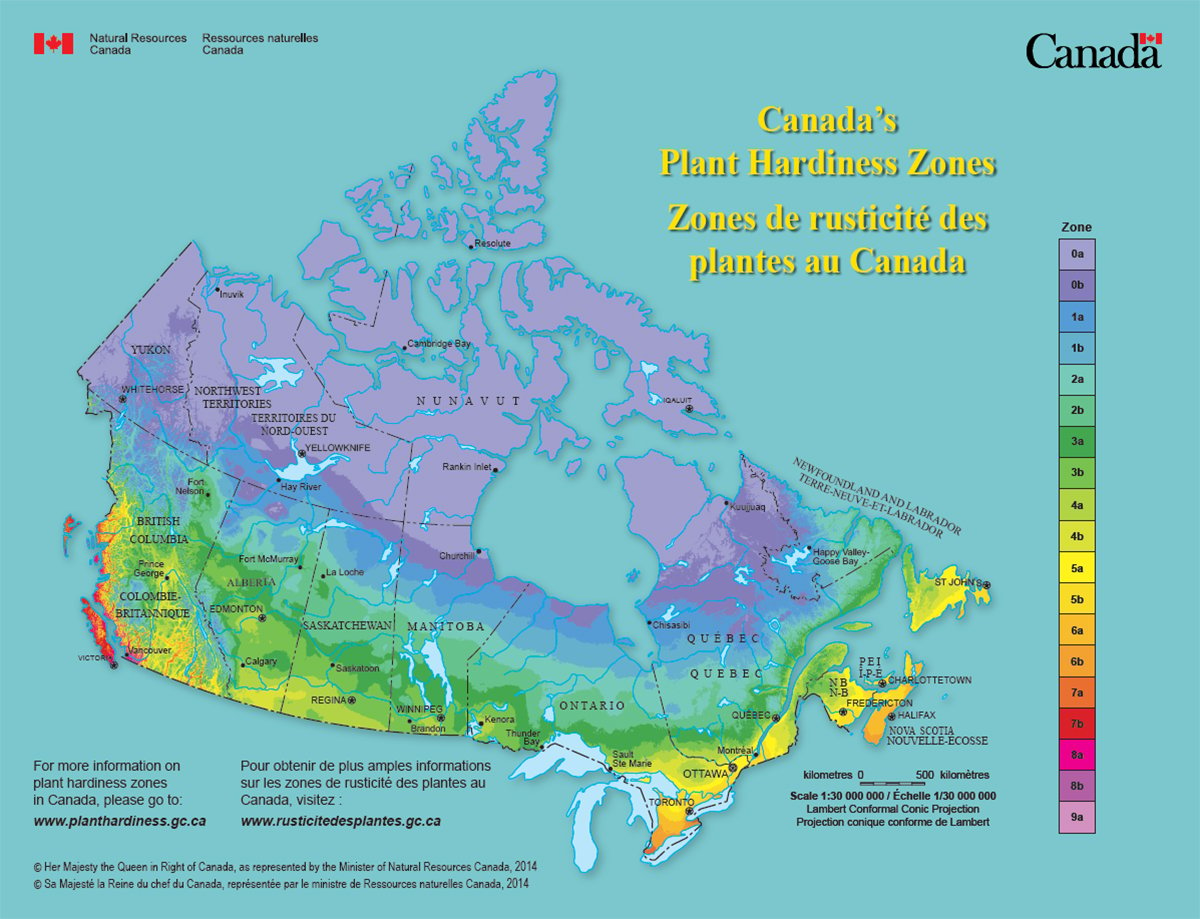

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

The Sturgeon River herd numbers more than 300 and ranges over 700 sq. kilometres in the southwestern corner of the park and about 50 sq. km of adjacent farmland.

Bison management specialist Lloyd O’Brodovich of Parks Canada said the herd’s unique free-ranging nature makes it a priority for the park. The animals range freely in the park, in forest management lease areas, in neighbouring provincial forest land and on private farmland in the nearby rural municipalities of Big River and Canwood.

O’Brodovich said this sets the Sturgeon River bison apart from more famous Saskatchewan herds, such as those in Old Man On His Back and Grasslands parks, which are fenced in and fed during the winter.

“The farm bison herds are not wild, they’re not free ranging, they’re not reacting with nature the same way,” he said.

The Sturgeon River bison are on their own.

“They have to fight the weather, fight the wolves, fight all the natural things in the ecosystem, plus they’re free ranging, they’re not fenced in.”

O’Brodovich said First Nations people kill 12 to 20 of the bison each year outside the park.

“That’s a factor, too.”

The rapid rise in the bison herd’s numbers came with growing pains.

The herd poses potential health and safety risks to local residents and livestock. Some local residents have seen bison behaving aggressively and worry about the safety of their family and livestock.

As well, several landowners in the area were affected by an anthrax outbreak in the herd last summer. Five bison carcasses were found on private land and 23 died in the park.

“We didn’t by any means find all of them,” O’Brodovich said.

The bison herd has also been blamed for damaging farmers’ fields, bales and infrastructure. In recent years, bison excursions onto private land, in numbers ranging from one to 300, have become routine.

That sparked the realization among many in the area and that action was needed. The Sturgeon River Plains Bison Stewards was formed in June 2006, a grassroots, non-governmental organization dedicated to the conservation of the Sturgeon River herd.

The group recognized that landowner acceptance was vital to preserving the bison herd and has focused its efforts on reducing the conflict between bison and local landowners.

“The stewards are a very unique organization and important because they’re dealing with the wild land-agricultural interface,” O’Brodovich said.

Lobbying by the bison steward organization has helped set up compensation for damage bison cause to crops, hayfields and bales. As well, a program has been established to help landowners fence off key bison areas and river crossings, and a vegetation-monitoring project helps landowners select plants less appealing to bison.

Three hazers were also hired to move bison off private land and back into the park.

Cindy Williams, a hazer, steward director and operator of C. G.’s Rustic Retreat near the park, said the hazers assess where the need is most urgent.

“There’s no sense in running off five bison if there’s 130 doing a lot more damage somewhere else.

“We would find out where the most urgent need was and we would start there.”

Depending on the terrain, the hazers used vehicles, all-terrain vehicles or horses. Williams said a typical hazing would involve 30 to 40 bison, but the largest group involved 180.

“We would put just enough pressure on them to get them back into the park. The slower the better, because once they’ve started stampeding, you’ve lost control of the group. That’s why it’s called hazing,” she said.

“We did that on a daily basis to let the bison know that they’re not welcome here.”

Stewards executive director Gord Vaadeland said the group is moving from short-term to long-term management, such as conservation easements and tourism strategy development.

“We want to turn the bison into a benefit to the community and an asset,” he said.

“I’d like to see it going more towards the opportunity side. I don’t think the landowners should be responsible financially by themselves without seeing some sort of reward because they are doing something that is absolutely for the public good.”

Vaadeland also operates a horse ranch and an adventure tourism company that takes people into the bush for multi-day horse rides.

He said he has had his share of bison in his horse pastures over the years.

“It can be a problem or it can be an opportunity. It depends on how you want to look at it. In our case we decided to look at it as an opportunity. It’s making lemonade out of lemons.”