University of Regina researcher says embedding wetland policy within an agricultural drainage framework is backwards

REGINA — Critics of a proposed wetland stewardship policy in Saskatchewan say it fails to properly address the issue.

Academics who sat in on consultations about the plan said it focuses more on agricultural development than retaining wetlands and habitat, and they don’t believe the Water Security Agency’s data that says 86 percent of Saskatchewan wetlands from a period in the 1870s are still intact.

They also said it’s wrong to base a policy on a few of their own short-term research and demonstration projects while ignoring years of scientific data.

Read Also

Using artificial intelligence in agriculture starts with the right data

Good data is critical as the agriculture sector increasingly adopts new AI technology to drive efficiency, sustainability and trust across all levels of the value chain.

Peter Leavitt, Canada Research Chair in environmental change and society at the University of Regina, has studied water in the province for 30 years.

He described parts of the policy as “lunacy.”

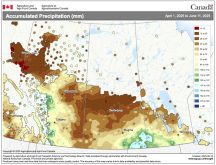

He said no one is going to be talking about drainage this spring unless there is some significant snowfall.

“And yet there’s a policy that’s going to get rid of 30 to 70 percent of the standing water,” he said.

Leavitt said embedding wetland policy within an agricultural drainage framework is backwards. It’s more useful the other way around, he added.

“You have a wetlands policy, and then farming is embedded in that,” he said in an interview.

“You’ve got to be able to separate drainage, which I don’t think anybody would oppose. Farmers need to drain standing water from big events and from snow melt. That’s fine. But you normally drain it into a wetland.”

The policy doesn’t contain any conservation or re-establishment measures, Leavitt said.

Farmers will often say water attracts more water, but if it’s all gone, then there won’t be any for evaporation and subsequent rainfall events to fill out crops, he said.

Leavitt also criticized the lack of meaningful enforcement in the policy and an inadequate ability to separately manage runoff and permanent wetlands.

“It isn’t appropriate to call wet land a wetland. It doesn’t have the same hydrologic function,” he said.

Water quality is already poor in many areas, and continued drainage into rivers and lakes adds to the problem. He said it takes decades to foul up the water and at least that to recover.

“Virtually all major water bodies are going to be threatened by this in the southern part of the province because water runs downhill, and at the bottom of the hill is where the lakes are, right?” he said.

Leavitt said hunters and fishers should be upset about the policy, too.

Phil Loring, an environmental social scientist associated with the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan, attended one of the consultation workshops. He said he came away from it feeling like it was consultation theatre rather than a participatory process.

“What worries me is that they’re calling it a wetlands stewardship policy, but really what it is is an agricultural growth policy,” he said.

“If you’re going to steward the wetlands, you need to be operating at a much bigger scale than this micro-watershed level where it’s almost like they’re saying you can pick a little corner of the watershed and just tinker with it and it won’t affect the rest.”

Both he and Leavitt questioned the assertion from WSA that 86 percent of wetlands are still intact.

“We would like to see the data,” said Loring.

“That number is not transparent, and as a person who is well-read on the ecological transformation of North American since the 1700s, I am highly suspect of that number.”

Aura Lee MacPherson, chair of the Calling Lakes Ecomuseum and the Saskatchewan Alliance for Water Sustainability, said the government has ignored calls from the provincial auditor since 2018 for a wetland policy. Her organization presented 2,300 letters to premier Scott Moe last summer demanding action.

“We want farmers to be very successful,” she said in an interview.

“But there should be enough water for all forever.”

MacPherson said she has a hard time figuring out why drainage is such a huge concern when the province is paying out billions in drought relief.

Leavitt agrees, and said it’s curious the government is developing a policy that would drain more water at the same time it’s planning a $4 billion project to irrigate more.

He said the province clearly loses more money to drought or dryness than it does from it being too wet.

Loring said it is possible to develop a wetland policy that coexists with agriculture. Two years ago the Global Institute for Water Security issued a comprehensive consensus statement on the ecological and social impacts of wetland drainage on the Prairies.

“We thought putting that out there was going to make it clear, here are some issues and here are some real practical ways to address it in policy,” he said.

“But when I brought that particular paper up in the workshop that I attended, all I heard was, ‘oh yeah we know about that.’

“They know the science is there. They’re not listening.”