X-ray scans help see through clouded daguerreotypes to discover portraits of people made between 1840 and 1860

The tarnish of time has stolen many 19th century photographic images captured through daguerreotype. Their sepia tones become spotted and the stern faces of those pictured are obscured, closing a window to history.

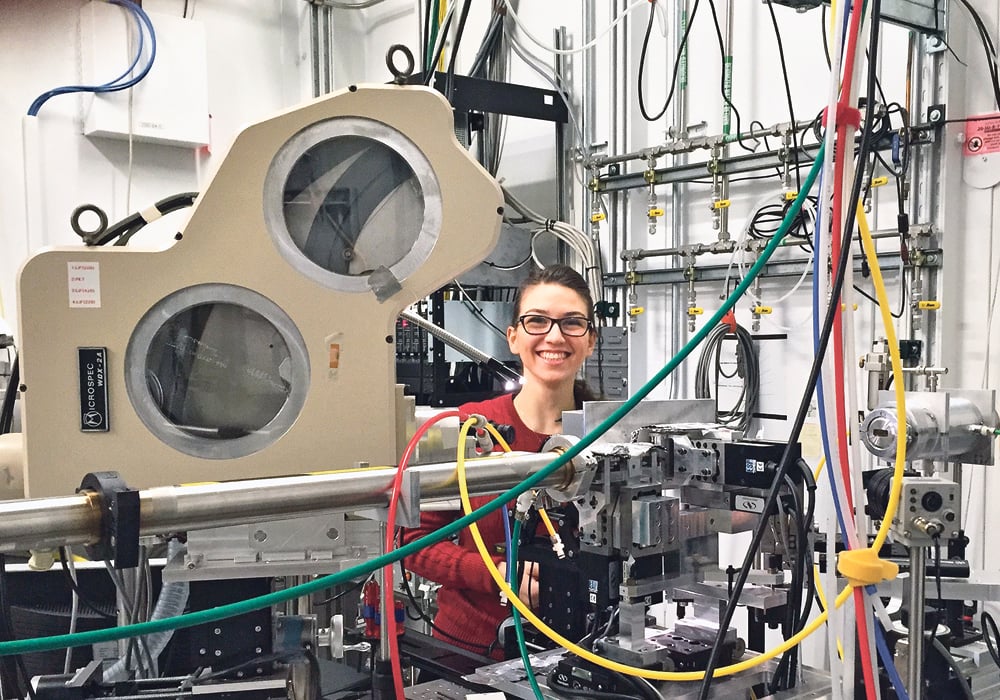

Madalena Kozachuk, a PhD student at Western University’s Department of Chemistry, has devised a way to reopen that window and is using the Canadian Light Source at the University of Saskatchewan to do it.

Kozachuk has found a way to recover hidden details from daguerreotypes that are tarnished or damaged beyond recognition, some of them more than 170 years old.

Read Also

Using artificial intelligence in agriculture starts with the right data

Good data is critical as the agriculture sector increasingly adopts new AI technology to drive efficiency, sustainability and trust across all levels of the value chain.

“I didn’t realize that that sort of results would be possible,” she said about the restoration technique. “It’s not something we expected at all. When I brought that back and presented it to my supervisors, they were speechless,” she said.

The daguerreotype was the first commercially successful process in the history of photography.

Around 1838, inventor Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre presented a unique way to capture an image on a silvered copper plate.

From 1839 to 1860, thousands of daguerreotypes were made worldwide.

Each image was made on a highly polished, silver-plated sheet of copper, sensitized with iodine vapour and exposed in a large box camera. It was then developed in mercury fumes and stabilized with salt water or sodium thiosulfate.

The image surface was fragile so many daguerreotypes were kept in wooden and glass cases.

Because the process was expensive and time consuming, only the wealthy could afford to have their portraits taken. Most of the remaining daguerreotypes are thus in institutional and private collections.

The images are like sterling silverware dishes and jewelry that blackens over time as the copper reacts to moisture and sulfur in the air. They tarnish faster in areas with high humidity and air pollution.

As part of her research thesis, Kozachuk was loaned several daguerreotypes from the collection belonging to the National Gallery of Canada. Each had deteriorated to the point where the images were virtually unrecognizable.

She used the synchrotron to shine an X-ray beam on the samples and then, using X-ray fluorescence microscopy, scanned them to generate two-dimensional images. These elemental maps provide information on the distribution of particles, which produce the range of grey tones that typify daguerreotypes.

Kozachuk also had access to the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source in Ithaca, New York. Using its rapid-scanning micro-X-rays, she was able to do full-plate scanning and see through the clouded daguerreotypes to discover portraits of people made between 1840 and 1860.

“By pairing those two techniques, you can not only get an image representation of the elemental makeup of your surface, but then you can also pair that with the absorption spectroscopy technique, which allows you to dig deeper into the chemistry of what’s actually going on with the plate,” she said.

“You’re not actually changing the plate whatsoever. You’re just looking at the (chemical) signal collected from the plate. So you don’t have to do any conservation treatment whatsoever to an object, but you can still retrieve the intended image behind all the corrosion.”

Her results could open new worlds for art history and preservation.

“To be able to bring the memory of this individual back into being is quite significant,” said Kozachuk. “It’s very impersonal from a data acquisition point of view but at the end of the day that’s still an image of a person.”

Kozachuk describes it as haunting to uncover the photographs of people and places that lie hidden from view under the veil of time and corrosion.

“To be that close to history is an amazing thing. When you have an object that has experienced a lifetime and seeing the evidence of that in various forms of degradation and tarnish, it certainly gives them a magical quality,” she said.

“Being around them is quite special. So much of our daily lives now is go, go, go and it actually forces you to stop and pause, which is quite the gift that it can afford the viewer.”

She said there are many aspects of the daguerreotype yet to be discovered, which makes her research a step toward unlocking lost images and the historic, cultural and artistic information they hold.

Further research is also underway into methods of preserving the plates to minimize fading and fogging, which involves a special chemical wash and electro-cleaning.

These methods will allow art curators to recover images on daguerreotypes and ensure they endure.

“It’s certainly quite interesting that you have to use essentially the most advanced technology we have at hand to look at very primitive technology,” said Kozachuk.

“This first form of the photographic process is still in part a mystery to us.”