NINGA, Man. – About 100 harvests have been taken from this field in years past. But now, according to Manitoba Natural Resources, it is a natural wetland and cannot be drained.

“What do they know about this land? They come here, see water today and say it is a wetland,” said Ray Hildebrandt.

Hildebrandt, his brother Bill, Doug Bartley and his three brothers know intimately the 300 acres that today are considered swamp. Once, most of the swamp was considered productive grain land. In fact, in 1994 the land was assessed on the tax role as farmland.

Read Also

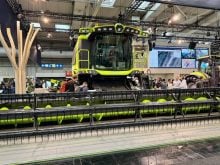

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

Then 1995 came. The land flooded, along with most low-lying areas in the Boissevain area in southwestern Manitoba. A road serving the community of Ninga was washed away. Rural municipalities that border the road paid to upgrade it, similar to an upgrade done a half dozen years earlier on a nearby intersecting road.

The two roads, now higher and wider, created a drainage problem for the land the roads divided – land owned by the Hildebrandts and Bartleys.

Before the upgrades took place, local municipalities commissioned a drainage study from the provincial natural resources department, which allowed for a drainage system in the new low-lying area created by the roads. But when work on the last road was nearly complete, the natural resources department and the provincial minister in charge of the department did an about-face and ordered the new drain closed. A 300-acre lake was born.

“Considering in our 1994 tax assessment it was nearly all assessed as arable land, and there was no mention of a lake, I am not sure what is going on,” said Ray Hildebrandt.

A series of wet years since has compounded the problem.

The small group of farmers says it attempted numerous times to meet provincial officials to get an explanation for the closed drain, but were refused.

“For nearly two years no one returned our phone calls. No one would meet with us. No one cared that their actions were costing us tens of thousands of dollars. They were busy building a wetland on our farms,” said Bill Hildebrandt.

The farmers said only when they cornered the regional head of the department, Bob Wooley, at a public meeting was a private discussion arranged. Wooley has not returned Western Producer phone calls.

Doug Bartley said the municipalities that built the roads shouldn’t have to take all the responsibility for damages.

“So far it is only a few farmers that have been made to pay for this wetland. If the government wants to build a wetland, let them pay for it. Confiscating a farmer’s land for one without compensation isn’t right,” said Bartley.

In August of last year Ray Hildebrandt tried to drain some of the water from his land. With a spade he cut through the earth berm holding back water on his fields. He said natural resources officers soon showed up at his farm and laid a charge of draining water without a permit.

“In court we found out that it was the first such charge ever brought against a farmer by natural resources,” said Michael Waldron, lawyer for Ray Hildebrandt.

Hildebrandt attempted to apply for a permit locally after the charge was laid, but said he was told by natural resources officials not to bother because it would be denied.

The issue has caused a rift in the community. Some neighbors who benefit from the new road to Ninga and it’s accompanying drainage system say that draining the new slough will cause downstream flooding of their land.

“There are too many parties involved in the matter. It has become complicated by local issues that we, as municipal councilors, feel have little to do with the water and more to do with local personalities,” said Dwight King, a councilor with the rural municipality of Turtle Mountain.

King said the council wants the water level lowered so most land can be farmed and the road protected from erosion.

The local pool elevator manager agrees.

“That road is very important to this local elevator. I was getting really concerned when trucks couldn’t get through to town to deliver grain. They (municipalities) fixed the road. But now it is washing away again and everybody’s hands seem to be tied about how to solve the problem… . Meanwhile a few farmers have lost a couple of quarters of land and the road problem will end up happening all over again,” said Grant Harder, of Manitoba Pool Elevators in Ninga.

King said before the issue can be resolved, they need to clear up the confusion over jurisdiction.

“We need to establish which drainage systems are the responsibility of the municipalities and which ones are to be managed by natural resources. Then this struggle over who is in charge of local drainage would be one less obstacle to be overcome.”

Waldron has filed a written argument with provincial court and hopes a ruling in his favor will determine where provincial natural resources have jurisdiction.

“Bottom line is that the department of natural resources shouldn’t have an interest in municipal water. It could be a dangerous precedent if the province has complete authority over all drainage issues affecting farmers,” said Waldron.

Slowly the newly upgraded road – and farmers’ patience – is being washed away by a metre of lapping water. The two families’ only hope of recovering their land now rests in the Manitoba courts. The parties expect the court to rule in September.